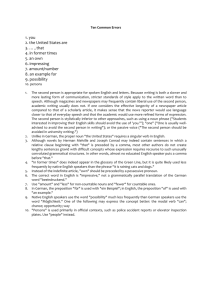

MS - Word 10 - Department of Economics

advertisement