Using Data to Motivate: An Inexpensive and

advertisement

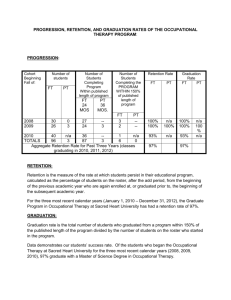

1 Using Data to Motivate: An Inexpensive and Student-Focused Approach to Retention Problems and Solutions Debbie Kepple-Mamros Director of Institutional Research and Coordinator of Retention Activities Graceland University kepplema@graceland.edu Abstract - Higher Education has come to accept that retention is a formidable challenge that only big data can help meet. In response a niche market has been developed by software providers who offer ‘retention solutions.’ While these programs may favorably impact retention, they tend to place most of the responsibility for ensuring success on the university. The expense of purchasing a ‘retention solution’ in addition to the personnel costs associated with installing the software, coordinating the program, possibly duplicating longstanding retention programs and coordinating student interventions can be cost-prohibitive. Graceland University has accepted that retention is a complex problem and that the solution to it must be data-driven but has rejected that this needs to be done by an outside provider. Utilizing a reporting system already in place, the institution harnessed data and put it in the hands of the individuals who can make actionable changes: the students. All students are sent information like personal class attendance records and midterm GPAs, which encourages improved personal responsibility. By recognizing that the solution could be internal Graceland has been able to improve retention and save money by developing the power of its existing tools and staff. Introduction Higher Education has come to accept that retention is a formidable challenge that only “big data” can help meet. In response a niche market has been developed by software providers who offer ‘retention solutions.’ These software solutions are sometimes too big or not nimble enough to target the root of attrition for some small institutions. A main cause of attrition is often each individual student’s academic experience (Demaris, 2008). This paper does not seek to discount the culture and socio-economic status of students and its impact on persistence. It’s well documented at all levels of education that income plays a large role in success (Payne, 2005). It also does not seek to diminish the role that student life, athletics and admissions can and should play in retention. Rather, it supports the theory that a key contributor to student attrition is the students’ academic experiences. Many areas across campus can favorably impact student success through both one-on-one interventions and systemic changes and it’s the students who potentially need interventions that most retention software seeks to identify. Still, the question lingers about whether retention products are successful enough to justify their costs. The primary thesis of this paper is that most small institutions have the ability to identify these students using their own data and institutional knowledge without spending tens of thousands of dollars for a product created by an outside provider. While some of the available products may favorably impact retention, the responsibility for ensuring success remains the university’s. The expense of a‘retention solution’ plus the personnel costs associated with installing the software, coordinating the program, possibly duplicating or usurping 2 longstanding and successful retention efforts and coordinating student interventions can be costprohibitive. Graceland University has accepted that retention is a complex problem and that the solution to it can be data-driven but has rejected that this needs to be done by an outside provider. Some of the retention solutions are great products with the ability to securely access your student information, set up a platform, store information in a cloud, and provide immediate alerts to staff when interventions are necessary. The analysis they provide based on either local data or national comparisons can also be valuable. However, institutions who find these products most useful are typically those who have come late to the retention game, like highly selective institutions who only recently noticed a retention decline or institutions whose funding was not entirely dependent on student enrollment. The economy of the last decade has changed higher education, and for the first time many small private colleges with small endowments are finding themselves at the leading edge. For most small private colleges, retaining students to graduation has been a priority since the 1980s. Retention directors or committees using good learning management and reporting systems allow small institutions to identify students in need of help and provide the personal attention for which small colleges are known. Graceland University is a small liberal arts institution located in one of the poorest counties in Iowa. Like many private colleges, Graceland was established in the 19th century by a Christian church. Its sponsors envisioned a non-sectarian institution of higher education open to all people regardless of religion, or financial or social status. As Iowa’s first regionally accredited junior college, it flourished as a two-year institution throughout the first part of the 20th century. Then in 1960, Graceland responded to economic and educational changes and transitioned to offer baccalaureate degrees. In January 1988, the institution responded to another societal need and launched its first distance learning nursing program. In the 1990s, acutely aware of the needs of both nearby community college students and the fragile smalltown workforces, Graceland established low-cost transfer opportunities at satellite centers at three rural community colleges. Then with the initiation of the first graduate program in 1995, Graceland reviewed and revised its mission to include graduate study. It now offers 34 bachelor’s degree options, master’s degrees in education, nursing and religion, and a doctorate in nursing practice from campuses in Lamoni, Iowa and Independence, Missouri as well as bachelor’s degree completion programs at satellite centers. Over the past several decades, Graceland has experienced another significant change, not unknown to other small colleges across the country. Graceland has always seen itself as fairly diverse for a small private institution in the Midwest but that diversity has changed. Prior to the 1990s, the majority of Graceland’s student population was associated with the sponsoring church. In Fall 1985, 82% of Graceland’s total student body were members of this sponsoring church. In Spring 2014, only 33% of students on the residential campus were members of the sponsoring church.1 In Fall 1985, 17.7% of the student body participated in athletics. In Spring 2014, 56% of the student body actively participated in athletics. In Fall 1985, the student body hailed from 42 states and 10 countries. In 2013, Graceland’s students came from 44 states, two territories and 32 countries. In Fall 1986, the earliest date for which Graceland has electronic records that indicate race and ethnicity, 89% of the student body were white US citizens. Of the other 11%, almost half of them were international students. In Spring 2014, the percentage of international students was higher, 9% compared to 5% nearly thirty years earlier, but the 1 The percentage is much lower if distance education students and those in the face-to-face completion programs are counted. In 1985, all Graceland students were associated with the residential campus. For accurate comparisons, all 2013-14 numbers will refer to the residential campus. 3 most significant change was in the number and percentage of members of minority groups. Just over 27% of Graceland’s student body now identify as non-white US citizens compared to 5% in 1986. More recent comparisons show that the number and percentage of low-income students has gone from 34% of the incoming class in 2002 to 52% in 2013, and the type of poverty has changed. Graceland is seeing more students who have experienced urban as opposed to rural poverty. We have also seen an increase in additional high-risk populations. Several students each year enroll after aging out of foster care. We are beginning to enroll students who grew up in migrant farm worker households. Finally, we are experiencing an increased number of traditional-aged students from out-of-state who are single parents, who lack a local, familial support system. One thing that has not changed much over the past 30 years is the students’ academic profile. Taking into account the changes in the scaled scoring, Graceland’s incoming classes today have the same ACT average of 21 as they did 30 years ago.2 Graceland’s students are academically average. Yet, many of them are under-resourced and lack more than just money or access to credit. An under-resourced student is a student who not only lacks access to money, but also lacks a support system and mentors who understand the system in which they, the students, are trying to succeed (Krodel, 2011). Many of today’s students come to college with assumptions that administrators and instructors fail to recognize - just as the students are incapable of recognizing the assumptions of the faculty. They lack the language and understanding of higher education. Many who come from underresourced schools, lack the vocabulary to comprehend lectures and written course materials. In addition, many students tend to arrive at college with a belief that intelligence is a fixed trait (Doyle and Zakarajsek, 2013). According to Terry Doyle and Todd Zakarajsek, in their work The New Science of Learning, “Each fall, tens of thousands of students enroll in classes that they do not believe they have the ability to pass. They also believe that hiring a tutor, visiting the professor during office hours for extra help, or even working harder will make no difference (Doyle and Zakarajsek, 2013).” Contemporary culture has made things more challenging. Many first generation students believe that seeking help is a sign of weakness. Many low-income students not only struggle to pay for required textbooks, they begin with the assumption that books are not a valid source of information and that they can navigate the classroom environment through their peers and instructors. In short, under-resourced students arrive in classes with some critical assumptions that need to be recognized and appreciated in order to make a difference in their persistence (Kirsch, 2013). Software has little chance of understanding or counteracting these traits. In the face of this changed situation and the retention challenges that come with it, it seemed like the perfect time for Graceland to contract with a vendor who offered a retention solution, and we explored three such products. While each product offered us something new, all overlapped with things we were already doing. And while adamant to improve retention, Noel-Levitz data indicated that our retention was already exceeding the expectations of our student profile. Graceland’s data in the CSRDE Retention Report from June 2014 compared favorably to institutions of similar size, academic profile and location (Whalen, ed., 2014). A 5-year average retention rate for first year students of 69.9% was good. Thus we 2 In 1989, the ACT was replaced with the enhanced ACT, which was a longer test and had different methods of scoring. The enhanced ACT average scores increased by 1.8 points across the US. Graceland’s first year class in 1985 had an average ACT score of 18.8. The 2013 first year class had an average of 21. A score of 20.9 was reported as the national average for students taking the ACT in 2013. 4 did not expect to experience the large retention improvement that the products were claiming. Most of the vendors insinuated that their pricing correlated to the expected retention gains. We were skeptical. Like most small institutions in the wake of the most recent recession, many programs and academic departments are constrained by shrinking budgets. Spending tens of thousands of dollars for a product that we had some reservations about just didn’t make sense. After much thought and planning, we decided to implement the main processes of these retention solutions using the systems and people we had in place. First Graceland acknowledged that many retention efforts were already in place. The University has had a TRIO Program in place for decades and has long had developmental courses that count for credit towards graduation. There is an understood institution-wide ‘mission’ to make personal connections with students. The research on class sizes has produced varying results, with some studies showing that class size has little impact on the factual knowledge students retain, and others showing students in smaller classes acquire problem solving and written communication skills much better (Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning). Graceland’s faculty pursue the latter outcome and have aggressively protected the caps on class sizes in order to promote student-faculty interactions, which allows them to teach these skills across the disciplines. As a result, less than 5% of Graceland’s courses have more than 44 students enrolled.3 While dated, research conducted by Steve Chatman in 1996 showed that 10% of course sections offered at universities nationally had greater than 44 students (Chatman, 1997). At Graceland, 63% of course offerings have fewer than 20 students, with an average class size across all undergraduate sections between 17 and 18. Graceland has had an Enrollment and Persistence Committee since the 1980s, and appointed a Coordinator of Retention Activities in 2010. Yet, we knew we needed more. Fortunately, in 2010, Graceland also transitioned to JICS, a Jenzabar product, and with that transition acquired its first learning management system. In the same year, the report writing system transitioned from Improptu to Cognos and new report writers were trained. Retention Solutions on a shoestring budget – or Homegrown Retention for Small Institutions Graceland’s faculty, staff and administrators, through experience, training and professional development, understand that many of our students, being under-resourced, don’t know how to monitor their own learning. They do not have the experience of following their progress in a course by adding up the points they have received and dividing that number by the total points possible. They have not had mentors to show them how to manage their time or create daily schedules. With the understanding that data could not solve these problems but rather identify students who needed help, Graceland set out to build its own retention solution step-by-step and completely customized. Utilizing Cognos and the learning management system, the institution harnessed data and put it in the hands of the individuals who can make actionable changes: the students. All students routinely receive information like personal class attendance records and midterm GPAs, which encourages improved personal responsibility. By recognizing that the solution could be internal Graceland has been able to improve retention and save money by developing the power of its existing tools and staff (Kelly, 2013). Expectations are now explicit: go to class, keep up with your coursework and focus on your academics. By making expectations 3 33 course sections out of 374 undergraduate offerings had 40 or more students registered. Graceland University, Institutional Research, Common Data Set, 2013. 5 explicit, which is absolutely necessary for under-resourced students according to Eric Jensen, individual instructors and the university as a whole are building hope, a necessity for high-risk student success (Jensen, 2009). In order to make sure students understand that we expect them to go to class, every class, every day, turn in all homework and strive for successful completion of 15 s.h. each semester, Graceland implemented multiple early warning systems each with the goal of promoting personal responsibility among the students. Attendance In fall 2010 Graceland began to require all instructors to record class attendance through the learning management system, Jenzabar’s eRacer. This move, the first in a series of steps to make expectations explicit using data, was controversial among some faculty members initially but has since been embraced. The learning management system’s attendance component automatically defaults to show each student as present. Instructors simply need to go in and make a choice from a drop down box for students who were tardy, absent-excused, or absent-unexcused. For students and instructors the difference between the three can be significant. An excused absence could allow a student to make up a quiz. Being tardy might allow the student to take the quiz and only be docked points after a certain number of late arrivals. Attendance records can be easily accessed by students and instructors but any benefit for the students stands on the assumption that they know to check the attendance portion of the course page and know that a high number of absences will negatively affect their learning and their grade. To combat this, two additional methods of communicating to students that attendance is important have been incorporated. Many instructors utilize an option with attendance that automatically sends an email to a student after they have missed so many class meetings, usually 3-4. It continues to send an email for each subsequent miss. The simple email message is shown in Figure 1: From: webadmin@graceland.edu [mailto:webadmin@graceland.edu] Sent: Thursday, September 12, 2013 1:57 PM To: sxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Subject: Absence warning for student xxxxxxxxxxxxxxin World Civilizations I This e-mail warning has been generated because Student xxxxxxxxxxx has 6 unexcused absences in World Civilizations I (HIST1310 (GC13) 1; Faculty: xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx). Figure 1: Absence Warning. The messages are not easily customizable but the benefit of even a canned message is that it tells the student that they were missed. Another layer was added to the attendance message at the suggestion of one of the men’s residence hall directors. IT programed the learning management system to show an individualized banner to each student with their total number of absences at the top of each page. Whenever a student logs in during the semester, the red banner will appear that states “According to our records, you have X absences this semester.” Additionally, there is a campus-wide effort to have conversations with students 6 emphasizing the importance of going to class. The students get the message that missing more than 10-15 class sessions in a single semester puts them at risk for falling out of satisfactory academic progress. This message is delivered in orientation meetings, in first year experience courses and in the residence halls. The goal is to instill the belief that missing class is not normal. Analysis of the results suggests that Graceland is moving closer towards that goal. Attendance taking and personal follow-up with students has correlated to improved class attendance. In fall 2011, fulltime students had an average of 16.4 absences per student per semester. In fall 2013, fulltime students had an average 13.8 absences per student per semester. For those of us using the data to understand and motivate students, the cumulative number of absences are used in several ways. Using Cognos to report information out of our database, several reports have been written to show students attendance. One report shows an individual student’s attendance for the semester (Figure 2). The report is available to be run by advisors, the Dean of Student Life and the Coordinator of Retention Activities. Attendance Report Student ID: 000000 Student Name: John Smith Classification: FF Cumulative GPA: 2.42 Course Work Course Number Course Work Course Title Present Excused Absent Unexcused Absent Tardy ENGL1410 Modern Rhetoric 21 0 1 0 HIST1310 World Civilizations I 21 2 5 0 INTD1100 Critical Thinkg Lib Arts-Science 22 2 0 0 MATH1310 Mathematical Concepts I 32 3 5 0 SCIE1250 Descriptive Astronomy Summary 16 2 2 0 112 9 13 0 Figure 2: Cognos 10 Attendance Report for Individual Student. Several other reports showing the full list of students and cumulative attendance information is automatically generated weekly and sent to specific people. These are also run daily during the first two weeks of classes each semester to help admissions and the Registrar determine which students may have not returned. The weekly reports have become a part of our warning system and alert advisors, coaches, hall directors and academic program directors to students who have missed a large number of classes in a given week. The data is used to reinforce appropriate behaviors and professional expectations. Figure 3 shows a sample of one of the reports. Recent Absence Report for All Students ID Number Student Name Session Present Excused Absent Unexcused Absent Tardy 999999 Samuel Jones FR 3 0 8 0 999999 Jane Doe JR 5 0 7 0 999999 Mary Smith JR 5 0 7 1 999999 Jose Hernandez SO 4 1 6 0 999999 DJ Grey SR 0 1 6 0 7 Figure 3: Cognos 10 Weekly Attendance Report Collaboration across areas on campus occurs when any one of our warning systems is triggered. Every Friday at 11am a retention staff meeting takes place that includes people from student life, academics, athletics, health services, TRIO program, international programs and religious life. The group gets a copy of the full attendance report for the week and a cumulative attendance report for the semester. Members of the group are assigned students of concern to contact. Welfare checks are conducted immediately for students who typically have good attendance and appear on the reports in a given week with a high number of absences. Those students who have chronic absence issues are followed up with by appointment. These interventions are not seen as urgent but are expected to happen with a few days of the report and assignment. A feedback loop is built into the process. By the following week’s meeting, each person who was assigned to follow up with a student reports back the results of the meeting. Graceland’s administration is confident that both the messages to the students about attendance and the interventions based on class attendance data have made a positive impact on student success as will be discussed below. MIDTERM GRADES AND GPA In fall 2012 Graceland began to require faculty to calculate and enter midterm grades for all students. Prior to this, only deficient grades were required and only students with a D, F or I at midterm got a notice. The act of recording some grades, but not all, confused the students and Graceland also felt it caused complacency. Students who did not receive a deficient midterm notice may have had all Cs in their courses and were truly at risk. For advisors, this practice provided an incomplete picture. The advisor would not know whether the student with an F in Statistics had all Cs in his/her other courses or all As and Bs, yet would make very different recommendations in the face of these two disparate situations. As with the attendance recording, this change met some resistance among the faculty. Some claimed it caused more work, while others took the philosophical stance that by providing too much information for students we were inhibiting the development of students’ self-efficacy. Nonetheless, the policy to require all students to receive midterm grades for all courses was passed by a large margin with the hope that it would improve students’ academic performance and thus improve retention. The change did not result in an overall improvement in the average session GPA for students. In the term prior to the introduction of midterm grades the end of session average GPA for all fulltime undergraduates was 2.99. At the end of spring 2014, the average session GPA was 2.97. In both sessions 15% of all fulltime undergraduates finished the semester with less than a 2.0 GPA. In spring 2014, there was a slight, but insignificant, increase in the cumulative GPA of enrolled students from 3.02 to 3.03. Well aware that the midterm grade notifications were not making a significant difference in academic performance, the registrar’s office put into practice the same philosophy we have applied to attendance: put the information in the hands of the individuals who can make actionable changes - the students. While students were already getting midterm grade notices, they were not getting midterm 8 GPAs and did not understand how to calculate or project a GPA. The registrar’s office made the decision to employ an element of gamification to the midterm grade message. Gamification is the use of game design elements in non-game contexts. In education this happens when students are visually presented with their progress in levels, points, or graphs that show progression. It can also happen through badging where students earn public recognition for an accomplishment or through a number of other gamesituations. In spring 2013, the systems specialist in Graceland’s Registrar’s office created a chart using Cognos that pulled midterm grades from the database. Using a very basic element of gaming and extending a car and road trip theme that had been used elsewhere on campus, students are now visually presented with their progress on a colored meter that looked like a car’s gas gauge or speedometer using the same colors as a traffic light. No data is available to report yet. Results will be assessed over the next several semesters. See Figure 4 for an example of the notice students receive. Figure 4: Cognos 10 GPA Meter Report for Student 9 FLAG FORM A final example of how Graceland created its own retention solution using tools and skills it already possessed is the creation of the FLAG (For a Lower Attrition Goal) form. The FLAG form is an alert or concern that any faculty or staff member can use to bring attention to a student at any time. Created by using the contained form portlet in our learning management system, the simplicity of this is that anyone who can use basic computer technology can create one. This form was rolled out in 2011 and every fall receives an updated introduction to the faculty and staff. A link to the form appears on multiple pages on Graceland’s internal website. When complete, the faculty or staff member clicks on the submit button and the form is automatically sent to both the Dean of Student Life and the Coordinator of Retention Activities. The form itself is shown Figure 5. FLAG FORM______ The primary goal of the FLAG Form is to help students succeed and graduate from Graceland University. Faculty and Staff should use the form to submit an academic or personal concern about a student. It facilitates student success by getting important information to staff, advisors and counselors for timely interventions. * Your name: XXXXX XXXXX * Student's name: Student ID (if known): Please explain the concern: Please tell us what you have done to address the situation. (see note) Please provide suggestions about how we might help the student? Note: If this is an academic concern or a personal concern and you have a relationship with the student, please find a time to visit personally with this student. If you would like assistance on how to start the conversation or what resources might be available, please call the Dean of Students. All concerns will be emailed to the Dean of Students, and the Coordinator of Retention Activities. Submit Figure 5: Jenzabar eRacer Contained Form used for Graceland’s FLAG Form While it might appear simplistic, it has proved to be very useful. On average 3 FLAGs are received weekly, although some weeks see a much higher number. Unless a FLAG alerts staff to a situation that needs immediate attention, the concerns are discussed and assigned for follow-up each week at the Friday retention staff meeting in the same manner as the attendance issues. The form and process 10 has been assessed in two ways. The first was through tracking students who were flagged against their end-of-semester GPAs. As expected an overwhelming majority of the FLAGs were for students who finished the semester with lower than a 2.0 GPA or who withdrew before the end of the semester. This might seem to suggest that the form is not working to improve academic performance, but it does show that the faculty and staff are very aware of who is struggling both in and out of class, an important step in improving retention. Conclusion Assessment of any retention initiative is essential. However, as with any education or social science research, causation is difficult to prove, especially with the rapid changes occurring in higher education today. In Graceland’s case, assessment is both qualitative and quantitative and evaluates both the individual initiatives and overall retention. An analysis of the individual results related to each of the initiatives was shown above. Qualitatively Graceland conducted a University-wide SWOT analysis via Survey Monkey in early spring 2014. Seventy-eight of 227 employees responded (34% response rate). Forty-nine of the 78 respondents specifically mentioned either attendance taking, midterm grades or the FLAG form as a strength of our current retention program. Finally, the most comprehensive quantitative assessment is shown in the actual retention and graduation rates. While first year cohort retention rates have remained stable, the University-wide undergraduate spring-to-fall retention rate has increased from 80.9% to 83.9% in three years and has been above the ten-year average of 82.2% for two of the last three years. It is too early to tell whether any of these policies will have an impact on 6-year graduation rates, however, the most recent 4- and 5-year rates are showing improvements. The 2008 cohort graduation rate after 4 years was five percentage points above the previous year (35.5% vs. 30.6%) and 2 percentage points above any of the previous five years’ rates. The five year graduation rate for this cohort showed an even bigger improvement, increasing over seven percentage points over the previous year. In fact, this cohort that finished its fourth and fifth years in 2012 and 2013 has a higher five-year graduation rate than any of the previous cohorts dating back to 2003 had in six years (52.3% in five years vs. an average of 48.8% in six years for previous cohorts or a high of 50.4% among them). The 2009 cohort is showing similar improvements over the 2003-2007 cohorts in graduation rates. Cohort Year Cohort Enrollment First Year Retention Rate Graduated w/in 4 Years Graduated w/in 5 Years Graduated w/in 6 Years 2002 267 72.70% 31.10% 42.70% 47.60% 2003 253 72.30% 33.60% 46.60% 49.80% 2004 305 73.40% 28.20% 43.60% 47.20% 2005 254 70.50% 30.30% 47.20% 50.40% 2006 251 76.80% 33.60% 46.80% 49.40% 2007 271 70.80% 30.60% 45.00% 47.60% 2008 197 72.10% 35.50% 51.80% 53.80% 2009 220 70.50% 32.30% 49.50% 2010 220 69.10% 2011 259 68.00% 2012 231 69.70% 2013 326 11 Undoubtedly Graceland is making other changes that affect persistence to graduation that might be influencing these numbers. For example, in fall 2013, a new work-study policy was introduced that guaranteed any student a job on campus if they wanted one. In addition, Graceland also now has a certified Bridges out of Poverty trainer on staff who presents regularly at professional development sessions. In the end, the essential message of this paper is that small institutions can create, implement and target their own ‘retention solutions’ to fit their needs without paying tens of thousands of dollars annually to an outside vendor. Works Cited Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, Class Size, Minnesota State University at Mankato. Retrieved 5/29/2014 http://www.mnsu.edu/cetl/teachingresources/articles/classsize.html Chatman, Steve. (1997) "Lower Division Class Size at U.S. Postsecondary Institutions" Research in Higher Education, 38 (5). Demaris, Michalyn, Kritsonis, William. (2008) The Classroom: Exploring its Effects on Student Persistence and Satisfaction. Focus on Colleges, Universities, and Schools 2(1). Doyle, Terry, & Zakrajsek, Todd. (2013) The new science of learning; How to learn in harmony with your brain. Sterling, VA: Stylus. Jensen, Eric. (2009) Teaching with Poverty in Mind. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. Kelly, Rob. (2013) A data-driven approach to student retention and success. Faculty Focus: Higher Ed Teaching Strategies from Magna Publications. http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/academicleadership/a-data-driven-approach-to-student-retention-and-success/ Kirsch, Irwin, Braun, Henry, Yamamoto, Kentaro & Sum, Andrew. (2009) America’s perfect storm: Three forces changing our nation’s future. State College, PA: ETS. Krodel, Karla, Becker, Karen, Ingle, Henry, & Jakes, Susan. (revised 2011) Helping under-resources learners succeed at the college and university level: What works, what doesn’t and why. Highland, TX: aha! Payne, Ruby. (2005) A framework for understanding poverty. Highland, TX: aha! Whalen, Sandra, ed. (2014) 2013-14 CSRDE Retention Report, Center for Institutional Data Exchange and Analysis (C-IDEA), Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Outreach.