![[1] true and false quiz](//s3.studylib.net/store/data/009087440_1-15af11b43336a062473c28407dd01f43-768x994.png)

[1] True and False Quiz

[2] T & F Answer Key

[3] Multiple Choice Quiz

[4] MC Answer Key

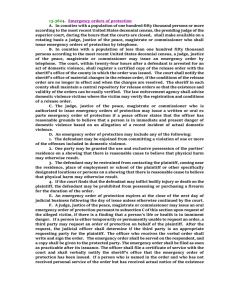

for use with Slomanson,

California Civil Procedure

in a Nutshell (5th ed. West: 2014)

[in progress]

All rights reserved

Answer keys below

“One of the specific examples of

trespass.alleges that...defendants

placed a foreign substance on

plaintiff’s coffee filter with the

intent of distracting and disturbthe plaintiff during a law school

entrance examination taken by

the plaintiff....”

---Pearlson v. Does 1 to 646, 76

Cal.App.4th 1005, 1007 (1999) (no

individual defendant named).

[1] TRUE AND FALSE QUIZ:

Chap 1

Q1: The California Constitution is the supreme law of the state.

Introduction Q2: Where the language of state and federal constitutional provisions are similar,

the federal constitutional provision preempts the California Constitution.

Q3: You may cite an unpublished case.

Q4: A law review article can never be a source of California law.

Q5: The CRC apply with equal force, as do the CCP.

Chap 2

Q1: A plaintiff seeking a monetary judgment must state the amount demanded in

the complaint.

Jurisdiction

Q2: A California cross-complaint, for less than $75,000, results in a limited case

being reclassified as an unlimited case.

Q3: California state and federal trial judges may decide the same type of case.

Q4: A federal judge will not hear a state law claim which, standing by itself, does

not trigger federal subject matter jurisdiction (SMJ).

Q5: A plaintiff must satisfy both the California long-arm statute, and the federal

Due Process check on state court exercises of in personam jurisdiction (IPJ).

Q6: The federal Due Process check—on state court exercises of IPJ over nonCalifornia defendants—would require a California state judge to assess

whether she could exercise either “general” or “specific” IPJ over a nonresident D.

Q7: California’s reasonable (i.e., due) diligence requirement applies to

defendants who are served via substituted service, rather than by personal

service.

Q8: A plaintiff must satisfy a two-element test for a valid exercise of quasi-inrem jurisdiction over property: (1) due diligence in trying to personally serve

the owner; and (2) Shaffer’s presence-plus (some other factor) requirement—

that the mere presence of the defendant’s property in the forum no longer

satisfies federal Due Process.

Chap 3

Q1: A case is generally subject to dismissal on venue grounds, when one of the

defendants resides outside of California.

Venue

Q2: A California state case—alleging job discrimination—can generally be filed

where the defendant resides, or where the discrimination occurred.

Chap 4

Choice

of Law

Chap 5

Pleading

Basics

Chap 6

Joinder

Q3: A case may be transferred from California to Arizona.

Q4: State and federal judges will likely dismiss an action, upon agreeing with the

defendant that there is a better forum outside of California.

Q5: Plaintiff’s choice of forum is given significant deference by a judge, when

she is considering a FNC motion.

Q1: In torts cases, the state where the wrong occurred determines which state’s

law governs.

Q2: P is from California. D is from Nevada. They have a car accident in Arizona.

P files her law suit in California. A dispositive defense is available under

Arizona law, but it is not available under either California or Nevada. The

California judge will apply California substantive law to this case.

Q3: A Florida franchisee’s contract clause with a California franchisor―providing that California law governs―subjects the Florida franchisee to the IPJ of

the California courts.

Q4: The governing law chosen by the parties to a contract resolves choice of law

issues.

Q1: Providing a notice of intent to sue a governmental hospital satisfies

California’s pre-filing notice statutes.

Q2: A complaint that advises the defendant why he is being sued will survive a

federal/state motion to dismiss/demurrer.

Q3: Heightened pleading is required when D possesses some facts that are within

its own particular knowledge, and unknown to P.

Q4: The amount of money damages sought must be stated in the complaint.

Q5: In a California state case, a plaintiff cannot obtain a default judgment when

the amount is not stated in the complaint.

Q6: Form pleadings are subject to attack.

Q7: A complaint is not subject to attack, if it could conceivably succeed at trial.

Q8: A special demurrer for uncertainty is appropriate, when it is unclear which of

two Ds is the target D for all charging allegations.

Q9: A defendant may appeal a judge’s adverse in personam jurisdiction (IPJ)

decision after trial.

Q10: After pleading a general denial, a defendant may win a case at trial on the

basis of the expiration of the SOL.

Q11: A defendant is barred from filing a cross-complaint after the running of the

SOL.

Q12: A plaintiff who files a complaint on the last day of the SOL cannot

thereafter sue a new defendant.

Q13: Once an amended complaint is filed, the original complaint is irrelevant.

Q1: Adding “Doe” Ds in the caption of the complaint makes anyone who harmed

the plaintiff subject to suit for three years after the filing of the complaint.

Q2: A plaintiff who should know the name of a potential defendant must

expressly name her as a defendant in the complaint.

Q3: A D, who has not been served within the diligent prosecution period for

serving all Ds, cannot be thereafter named and added as a party to the

lawsuit.

Q4: A class action plaintiff may aggregate the claims of the individual class

members to achieve the minimum amount in controversy.

Q5: P pays cost of the class action notice of suit.

Q6: A class action denial is normally appealable prior to judgment.

Chap 7

Truth in

Pleading

Chap 8

Case Management

Chap 9

Motion

Practice

Chap 10

Discovery

Q1: Pleadings must be subscribed.

Q2: A lawyer who signs a complaint can be sanctioned, when there is a defense

judgment.

Q3: A lawyer can be sanctioned for bad faith conduct at the pleading stage, by

filing a frivolous pleading.

Q4: P sues D for defamation, in connection with some public issue. But P cannot

win the case—because D’s defense is that the statement was true. D’s antiSLAPP motion will be granted.

Q5: The court first determines that D was engaged in protected activity. P will

nevertheless prevail (i.e., anti-SLAPP motion denied), if P’s pleadings and

affidavits demonstrate that P could satisfy the preponderance of the evidence

standard.

Q6: A P intends to drive D out of business by filing a complex lawsuit against D.

D will prevail on D’s anti-SLAPP motion.

Q7: Assume that: (1) D can demonstrate that he is engaged in constitutionally

protected activity; and (2) the P could not demonstrate the likelihood of

prevailing. D’s anti-SLAPP motion will be granted in these circumstances.

Q8: The case is filed in federal court. A California-styled anti-SLAPP motion is

filed by D. The judge must deny the motion, because it is not a federal

motion.

Q9: Discovery proceedings are stayed, pending resolution of an anti-SLAPP

motion.

Q1: Disposition on the merits and judicial efficiency both drive California’s case

management system. Each is entitled to equal weight in matters involving

judicial discretion.

Q2: Superior Court cases are subject to dismissal, when the plaintiff fails to serve

the defendant within sixty days of filing the lawsuit.

Q3: The judge must grant a continuance in Fast Track cases.

Q4: The judge cannot issue a terminating sanction for violating Fast Track rules.

Q1: The notice for most motions is mailed to the lawyers for all parties who have

appeared in the lawsuit. The moving party must provide a minimum of

sixteen court days notice of the hearing whereat s/he will seek relief.

Q2: Refer to Table 10BA: Statutory Notice Period. Motions must be noticed within

these statutory minimum times.

Q3: The statutory limitation—that new facts or law are the only basis for a

previously decided matter to be reconsidered—means that there is no second

opportunity to reconsider the same motion.

Q1: Witness information, and relevant documents, must be provided to your

adversary at the outset of the lawsuit—without her asking for it.

Q2: In both state and federal court, mental impressions are absolutely protected

from discovery under the work product doctrine.

Q3: When you inadvertently provide confidential information to your adversary,

Chap 11

Nontrial

Disposition

she must advise you within thirty days.

Q4: One may inquire only into matters which are relevant to the plaintiff’s claim,

or the defendant’s defense.

Q5: In both systems, one may inquire only into matters which are admissible

under the state or federal rules of evidence.

Q6: In California, one may propound 35 interrogatories.

Q7: One has thirty days to respond to your interrogatories.

Q8: For an entity deposition, the party noticing (who will take) the deposition

states the name, address, and other contact information of the person who

will be deposed.

Q9: A plaintiff seeking damages for emotional distress in a car accident case is

subject to a defense mental examination.

Q10: Failure to respond to requests for admission results in the matter contained

therein being admitted.

Q11: P identifies A and B as potential witnesses that P will use at trial. D does

not seek any updates from P. P will be able to offer the trial testimony of

witness C at trial.

Q12: Discovery sanctions serve the purpose of achieving the exchange of

information, in addition to punishing one who unreasonably frustrates that

policy.

Q13: The condition precedent to a California plaintiff obtaining information

about a D’s wealth is that punitive damages must be in issue.

Q14: For electronic discovery not retained in a readily accessible format, the

demanding party pays.

Q1: When the parties agree to arbitrate, each is necessarily precluded from

judicial review—even when the arbitrator’s award is wrong on the facts and

applies the wrong law.

Q2: Public policy is an exception to the arbitrability of a dispute.

Q3: A contractual arbitration clause, that is unmistakably one of adhesion, is

unconscionable.

Q4: A party’s conduct may result in waiver of the right to arbitrate.

Q5: When a judge refers a case to judicial arbitration, she thus violates the state

Constitutional right to jury trial.

Q6: Mediation is comparable to arbitration, because the decision-maker is the

same.

Q7: Mediation discussions, and related offers of settlement, are always

confidential.

Q8: Arbitrators enjoy immunity from suit when related to their relevant tasks.

Q9: A California defendant who defaults, either by not answering the complaint,

or because of a discovery sanction, will have to pay more than the amount

stated in the prayer of the complaint.

Q10: The parties settle a case. A dispute arises, regarding the terms of the

settlement. The judge is powerless to help them.

Q11: A settlement offer may be revoked.

Q12: A California counter-offer revokes the offer.

Q13: A California P’s settlement with one of multiple defendants can result in the

Chap 12

Trial

Chap 13

Securing &

Enforcing

Judgments

Chap 14

Costs &

Fees

settling D being sued again by joint-tortfeasors seeking their right to

contribution.

Q14: A state P has three years to serve all Ds. Any subsequently served D can

move to dismiss the case as to that D.

Q15: A California civil case must be brought to trial within five years of filing.

Q16: To obtain summary judgment in either state or federal court, one must

negate the opposing party’s claim or defense.

Q17: The party moving for summary judgment must provide fourteen days notice

of the hearing, assuming personal service of the motion on the adverse

party.

Q1: Paul files a claim against Dan, seeking both legal and equitable relief―

involving common issues of fact. The factfinder will be a jury.

Q2: The parties may enter into a pre-dispute contract to waive the right to jury.

Q3: Unlike federal six-person juries, twelve jurors are required in California.

Q4: Trial lawyers do not have to state a reason for the peremptory challenge of a

juror.

Q5: A lawyer cannot appeal a California judge’s decision denying a challenge for

cause.

Q6: Instructions taken from the CACI are proper instructions for a jury.

Q7: In California, the liability of two or more defendants is now several rather than

joint.

Q8: A compensatory-to-punitive damages a ratio of no more than nine-to-one is

the presumptive maximum allowable.

Q9: A motion for relief from judgment is lodged pursuant to California’s statute

(CCP § 473). It claims that a mistake constituted excusable neglect. If the

court agrees that the mistake was excusable, the motion must be granted.

Q1: All property is generally attachable.

Q2: Attachments are designed to provide the plaintiff with the ability to require a

defendant to litigate in the forum.

Q3: A California attachment of a defendant’s property is limited to cases alleging

breach of contract in a business context.

Q4: Due Process requires advance notice of an application for an attachment

order.

Q5: Due Process requires advance notice of an application for an order seeking

an injunction.

Q6: One can be jailed for contempt of court. When imprisoned, the nature of the

contempt is criminal.

Q7: A sister state judgment is not a judgment lien in California.

Q1: Costs must be awarded to the party who wins the case.

Q2: The cost of preparing models/blowups/exhibits, and photocopies of exhibits

will be recovered by the prevailing party.

Q3: A court may award reasonable attorney’s fees to the plaintiffs under the

Private Attorney General doctrine, if the societal importance of the relevant

public policy is proven.

Q4: The prevailing party is entitled to costs and attorney’s fees.

Q5: A California trial judge will deny costs to a plaintiff who filed an unlimited

Chap 15

Appellate

Review

Chap 16

Prior Suit

action resulting in a judgment within the monetary limits of a limited case (25k

or less).

Q1: A California trial judge’s order must be reviewed via writ.

conveniens.

Q2: You cannot raise an issue on appeal that was not raised in the trial court.

Q3: The “death knell” doctrine supports the automatic appealability of a class

action denial.

Q4: A disqualification of counsel order is automatically appealable.

Q5: One must file notice of appeal within the specified period for doing so. There

is no discretion to extend this period.

Q6: A judgment is enforceable, regardless of whether it has been timely

appealed.

Q7: Parties should receive an error-free trial.

Q1: A new statute is applied prospectively.

Q2: A new case is applied retroactively.

Q3: A California court will focus on the wrong of the defendant, and thus expect

the plaintiff to plead and resolve all possible remedies flowing from that

wrong in Suit One.

[2] TRUE AND FALSE—ANSWER KEY:

Chap 1

A1: True, if only state law is in issue. False, where the federal law—e.g., a federal

statute—provides the required governing law in a state case.

Introduction

A2: False. Generally, there is no conflict, just because the language is similar.

True, in those situations where state law cannot violate those portions of the

US Constitution applicable to the states—such as US SCt Due Process-based

case law regarding personal jurisdiction.

A3: False in California. True in California’s federal courts.

A4: False (only), because such scholarly publications are a secondary source

which may be consulted for ascertaining the content of the law.

A5: True generally. False, however, where they conflict with the CCP or another

statute.

Chap 2

A1: True, especially in California. A demand “shall” be stated in a California

complaint (subject to Nut § 7–2.B.1 personal injury/wrongful death

Jurisdiction

exception). False, because neither the FRCP nor the Judicial Code

specifically require the plaintiff to state an amount—although some amount

should be stated for a complete federal question claim, and to demonstrate

the “in excess of $75,000” requirement for diversity-based claims.

A2: True, if the cross-complaint’s amount in controversy is more than $25,000.

False, if the amount stated is less than $25,000.

A3: True, generally, if: (1) the case is a federal question case; or (2) a diversitybased case, wherein the amount sought is greater than $75,000. False, if the

issue: (a) falls within the exclusive jurisdiction of the federal courts (e.g.,

bankruptcy); or (b) is pre-empted by the federal Constitution’s Supremacy

Clause.

Chap 3

Venue

Chap 4

Choice

of Law

A4: True generally, because a claim filed in federal court—that does not present

either a federal question, or a $75,000+ state law claim (alternatively, if the

parties are not diverse)—cannot be heard in federal court. False, when

supplemental SMJ exists. Note: A federal judge may, of course, dismiss the

state portion of a federal complaint involving the same common nucleus of

operative facts, on the limited bases authorized under federal law (28 USC §

1367(d)).

A5: True, because a plaintiff in both systems must generally satisfy this two-step

process. California’s code-specific long-arm statutes contain various hoops

through which a P must jump, if IPJ is questioned by D (or the court). False,

when California’s general IPJ statute is the basis for asserting IPJ (CCP §

410.10). It authorizes exercises of IPJ on any basis not prohibited by the

state or federal Constitutions.

A6: True, in the sense that state judges typically use this distinction to analyze

IPJ issues. False, however, in the sense that the federal Due Process check

refers to the outer limits of Due Process—as determined by the US SCt,

which is the final arbiter of applications of such federal constitutional

principles. While judges in both systems have employed the generalspecific IPJ distinction, the US Supreme Court has never mandated its (thus

optional) use.

A7: True, when serving an individual defendant. False, when serving entity

defendants—because they cannot be “personally” served (because they are

technically served via substituted service only).

A8: True, in federal court, given the post-Shaffer FRCP amendment which added

requirement (1), after (2) was imposed on all courts by the US SCt. False, in

state court, unless the California Legislature were to add (1) to the federal

constitutional requirement imposed by (2).

A1: True in federal court, per 28 USC ' 1391(a)(1)-(2). False in California, per

the CCP ' 395(a) default rule, authorizing venue “where the defendants or

some of them reside.”

A2: True, because P has this choice under the general venue statute and the

FEHA venue provision. False, in the sense that a special venue statute

normally trumps the general venue statute. Brown.

A3: True, in federal court. False in state court, because the distinct state courts

cannot transfer cases to other jurisdictions.

A4: True, once the plaintiff advises the court that the defendant has satisfied

conditions of a dismissal via appearing in the alternative forum. False,

because a stay is the preferable remedy, until the defendant complies with

the conditions making a FNC dismissal appropriate.

A5: True, in general. False, as to non-resident plaintiffs.

A1: False, generally, because California (and most states today) apply an interest

analysis to resolve COL issues. True, in the narrow sense that the state

where the wrong occurred may have the strongest interest in the application

of its conflicting law.

A2: True, in that: (1) a judge normally applies local law unless a party otherwise

indicates; and (2) California’s substantive law includes its body of COL

Chap 5

Pleading

Basics

precedent. False, if a false conflict is present; e.g., Arizona has no interest in

the application of its law—which D would prefer to offer as a defense. But

the accident involved two non-residents of the forum. Arizona has no

articulable interest in the governing law question in the California court.

Even if a true conflict were somehow presented, Arizona’s interests would

not outweigh that of California or Nevada on these facts.

A3: False generally, because IPJ and COL may be related, but are distinct issues.

True, if the Florida franchisee has the requisite contacts with California.

A4: True, generally. False, if the state chosen bears no relationship to the

parties/transaction; or there is no reasonable basis for the parties’ choice.

Even if one of these alternatives is met, application of the chosen law’s state

must not violate a fundamental California public policy.

A1: True, assuming that the notice contains the essentials of both notice

requirements for suing a governmental entity—and a health care service

provider. False, if the notice does not provide the distinct essentials of both

of the relevant statutes. Wurts.

A2: True, assuming it satisfies the new “plausibility” application of federal

notice pleading. False, under California law, if the complaint puts D on

general notice about why he is being sued, but omits a fact (or prima facie

element) that is required for him to prove his case at trial.

A3: False generally, because the respective judicial systems (plausible/fact

pleading) do not generally contemplate this situation. True, assuming the

case is the type of case—e.g., fraud—where particularity in pleading is

required, but is accompanied by a lowered pleading expectation when D

presumably has such knowledge that P needs to prove his case.

A4: True, per California’s general rule. Although not technically required in a

federal complaint, Diversity Jurisdiction cases should include an amount.

False, in a California PI/WD case & in any punitive damage claim.

A5: True, generally—and, if a Statement of Damages (SOD) has not been served

on D in a PI/WD case. False, if a SOD has been served.

A6: True in California. Likely false, in federal court. DSW v. Zina Eva.

A7: True, although quite generally, in both judicial systems. False in both

systems, if it: (a) fails to cross the line from a possible to a plausible claim,

in a federal court; and (b) does not contain facts that match all elements of

the cause of action, in a California court.

A8: True, generally. False, in limited civil cases, because of the Economic

Litigation Project which prohibits special demurrers in this case category.

A9: True, in federal court. False, in California—which requires a writ proceeding

shortly after the judge’s initial finding regarding IPJ.

A10: True, if the affirmative defense of the SOL was filed with the answer—or,

via a pre-trial amendment to the answer. False, because of D’s waiver by

failing to assert this affirmative defense in the pleadings.

A11: True, generally. False, if the plaintiff’s complaint is filed prior to the

running of the SOL applicable to a compulsory cross-complaint.

A12: True generally, in both state and federal court. False, in federal court, if the

“new” defendant knew or should have known it was the target defendant

Chap 6

Joinder

Chap 7

Truth in

Pleading

but for a mistake in identity. False in state court, if the “new” defendant

was a properly named and charged “Doe” defendant.

A13: True generally, because there is but one complaint in a civil action. False,

where an unexplained change purports to avoid an earlier admission—

under the sham pleading doctrine.

A1: True generally, per the Doe pleading statute. False, where the plaintiff has

failed to include charging allegations in the complaint (and, a Fast Track

case will normally be resolved within two years of filing).

A2: True, if the plaintiff cannot properly claim ignorance of that person’s true

name. False, if P did not actually know—even though she could have

ascertained—the “Doe’s” true name. Fuller.

A3: True generally, in both the state and federal systems. In federal court,

however, a “mistaken identity,” regarding the target defendant’s actual

name, allows the plaintiff to add the target D after the 120-day federal period

for service—if that individual/entity apparently received notice of this suit

within the 120-day federal service period.

A4: True in California. False in a federal Diversity Jurisdiction case. However, if

the representative’s claim is over 75k, the court may exercise its

supplemental jurisdiction to hear the case. Allapatah.

A5: True in federal court. False in California, where a judge may allocate the

costs of notice among the parties.

A6: True in California. Richmond. False in federal court, where class action

appeal is discretionary with the appellate court.

A1: True, as to subscription by the lawyer. Generally false, as to subscription by

the client—absent specified exceptions, such as suits by or against a

governmental entity.

A2: False (only), because the frivolous pleading sanctions statute addresses

pleadings, not ultimate judgments.

A3: False generally, because CCP § 128.7 is designed for frivolous pleadings.

True, if the lawyer has also engaged in some conduct that violates CCP §

128.5.

A4: True, if: (1) the D was engaged in constitutionally protected activity; and (2)

if P cannot establish a probability of success. False, in the sense that the

merits (truth) are not conclusively determined at the anti-SLAPP motion

stage.

A5: False generally, because this is more than P has to show to prevail. P need

only make a prima facie case re her likelihood of prevailing. True, in the

sense that if P in fact makes a prima facie case that she will prevail at trial,

then she should initially prevail against D’s anti-SLAPP motion.

A6: False generally, because intent is irrelevant. Equilon. True, if: (1) either P

fails to tender a prima facie case against D via the pleadings and affidavits;

and/or (2) D was engaged in commercial speech, within the meaning of the

commercial speech exemption barring from filing an anti-SLAPP motion.

A7: True generally, because these are the two steps in anti-SLAPP motion

procedure. False, if the law suit is either: (a) a public interest suit; or (b) a

case involving commercial speech, both of which would preclude the D from

filing an anti-SLAPP motion.

A8: True generally. False, because some Ninth Circuit opinions have embraced

this motion, as long as not considered contrary to fundamental federal

policy on the facts of the particular case.

A9: True generally (and a major reason why some federal courts have denied

such motions). False, when the judge may authorize limited discovery, upon

a showing of good cause. CCP § 425.16(g).

Chap 8

Case Management

Chap 9

Motion

Practice

Chap 10

Discovery

A1: True re sentence one. False re sentence two, because litigation on the merits

normally trumps, in the event of a conflict. Hernandez.

A2: True, in counties applying the minimum period permitted by the Cal. Gov’t

Code. False, in counties where local rules provide a longer period within

which to serve the defendant (and federal court, with its uniform period of

one-hundred twenty days to serve all Ds).

A3: False, generally. True, if not to do so would result in a miscarriage of justice.

A4: True, in the sense that this rarely occurs. False, in those instances where the

judge has provided notice and opportunity to be heard, no lesser sanction will

be effective, and fault lies with the client rather than the lawyer. Ji Hae An.

A1: True generally, if personally served on the other lawyers. False, given that

“mailed” service necessitates an additional five calendar days for proper

minimum notice of the hearing.

A2: True generally. False, in the instance that a party may obtain a court order

shortening time, because of exigent circumstances.

A3: True generally. False, because a judge may—with proper notice to the

parties—reconsider, and then change, her earlier decision. Le Francois.

A1: True in federal court, because this initial core discovery is required. False in

state court, where the parties decide what to ask for and when.

A2: True as to the attorney’s mental impressions about the case. False as to the

consultant expert, whose mental impressions fall within the conditional work

product doctrine.

A3: False, in the sense that Rico requires her to contact you immediately upon

realizing that it’s confidential―which may be a matter of days. True, in the

limited sense that she may have to contact you within thirty days of her

receipt, if that’s when she first realized its confidential nature.

A4: True in federal court, although the exception authorizes “subject matter”

relevance on a showing of good cause. False in state court, because you may

inquire into “subject matter” relevance.

A5: False (only), because one may also inquire into matters which could lead to

admissible evidence at trial.

A6: True, given this statutory maximum for unlimited cases, and if the

submitting party used the total of 35 discovery events for just interrogatories

in a limited case. False, because one may propound any number of form

interrogatories.

A7: True, per the “rog” statute. False, if mailed (which is usually the case),

because of the additional time required for mailed service per CCP §

1013(a).

Chap 11

Nontrial

Disposition

A8: True, in the sense that one may of course do so, if a particular deponent is

desired. False, however, in the sense that the entity normally designates the

person most knowledgeable regarding the subject matter identified in the

deposition notice.

A9: True, but only if P’s claims somehow include a substantial claim for

intentional infliction of emotional distress, or like theory. Normally false,

because P seeks damages for negligence only. Any emotional distress

associated with the accident does not authorize a defense mental

examination.

A10: True under federal practice. False in California, where the requesting party

must make a motion seeking the matter to be deemed admitted.

A11: True in California, where there is no duty to supplement prior responses.

False in federal court, where such initial core discovery must be updated

by P.

A12: True in federal court. False in California, where punishment is not part of

the discovery sanctions landscape.

A13: True, because without such an allegation, wealth would be irrelevant.

False, because P must also obtain a court order authorizing such discovery,

predicated on P’s probability of success.

A14: True, per California statute. Generally false in federal court, where the

presumption is that costs will not be shifted to the demanding party.

A1: True, generally. False, given the two statutory bases for review— correction

and revocation—and some non-statutory bases, including unconscionability.

A2: False, generally, per Moncharsh. True, where the specific public policy

involves an unconscionable arbitration clause.

A3: False generally, because courts acknowledge adhesion contracts as virtually

unavoidable. True, if the adhesion involves both procedural and substantive

unconscionability.

A4: False generally. The aggrieved party should petition the court for assistance

with moving the arbitration along. Engalla. True, when the parties engage in

extensive litigation conduct, and one ultimately invokes an arbitration

provision—in circumstances prejudicing an adversary who has incurred

significant costs and attorney’s fees. Sobremonte.

A5: False (only). The result of a judicial arbitration is not binding, as opposed to

true arbitration—where the parties effectively agree to waive a jury trial. In

the former, either party has the right to a trial de novo.

A6: False (only). Unlike arbitration, where the parties get a result from a thirdparty (arbitrator), the mediator’s role is not to decide the case—although a

mediator does attempt to facilitate a settlement agreement by the parties.

A7: True, generally. False, when the crime-fraud exception applies (as with other

privileges).

A8: True generally. False for an arbitrator who does nothing, resulting in a

petition filed with the court to force him to specifically perform his

contractual obligations.

A9: Generally false, because the prayer is normally a ceiling above which a

defaulted D will not have to pay damages. True, where the P has served a

Chap 12

Trial

statement of damages in a PI/WD case.

A10: True, if the case has been dismissed. False, if they retained the jurisdiction

of the judge to enforce the settlement via a CCP § 664.6 agreement.

A11: True in state court—because of the longer thirty-day period that it remains

open. False in federal court—where the offer of judgment period is only ten

days.

A12: True under general contract law. False when it’s a § 998 settlement offer.

Poster.

A13: True, under state tort/procedural law. False, if there has been a § 877.6

good faith settlement determination by the court.

A14: True, under California’s general Diligent Prosecution Statute. False, if the

case is a general civil case (counties may employ as low as a sixty-day

period).

A15: True, under California’s general Diligent Prosecution Statute. False, under

California’s Trial Delay Reduction Act, where all cases are supposed to be

resolved within two years of filing.

A16: True, as this is the traditional method. False, in the sense that one can also

succeed, by showing an absence of evidence―especially on the eve of trial,

after discovery has run its course.

A17: True in federal court. False in California, with its unique 75-day minimum

notice period for this motion.

A1: True in federal court, where the jury must be the first to decide all overlapping “at law” issues involving money damages. False in state court,

where the “better practice” is for the trial court to determine the equitable

issues before submitting the legal ones to the jury—possibly leaving nothing

for a jury to decide. Hoopes.

A2: False in California (other than arbitration or decision by a referee), because

the CCP limits the methods for waiving the right to jury. True in federal

court, because under federal law, parties may contractually waive their right

to a jury trial. Applied Elastomerics.

A3: True generally. False, where the parties have stipulated to an Expedited Jury

Trial.

A4: True generally. False when her strikes are for impermissible reasons,

including race, gender (under applicable federal law) and sexual orientation,

religion, and “similar grounds” in California.

A5: False generally, because juries must not include biased jurors. True, if he

fails to use a peremptory challenge to strike a juror whom he unsuccessfully

challenged for cause.

A6: True generally. False where erroneously given on a matter that was not in

the trial evidence.

A7: True as to non-economic damages. False as to economic damages.

A8: True generally. False, in both systems, in a case involving: (a) relatively low

reprehensibility, and (b) a substantial award of non-economic damages.

Roby.

A9: True, when the lawyers’ mistake resulted in a “default or dismissal” for

which the client had no responsibility. False in other cases, because the statute

Chap 13

Securing &

Enforcing

Judgments

Chap 14

Costs &

Fees

Chap 15

Appellate

Review

Chap 16

Prior Suit

vests discretion in the trial judge to grant or deny the motion.

A1: True, as to business entities. False, as to individuals. (Fed relies on CA

remedies.)

A2: True, as to jurisdictional attachments. False, as to security attachments—

where D has already appeared, but P may lose the benefit of a resulting

judgment.

A3: True, generally as to business-related litigation. False, however, for nonresident defendants, to whom such limitations do not necessarily apply.

A4: True, generally. False, where P makes the requisite showing of irreparable

harm, were pre-order notice to be given.

A5: True, generally. False, where a TRO may be necessary for the preservation of

the status quo—until a noticed hearing occurs.

A6: True, if D was jailed for offending the court. False, if D disobeyed a court

order, and could avoid jail by compliance with the court’s order.

A7: True, when the judgment debtor has taken no action to reduce it to a local

judgment. False, because it may be reserved on the owner, then registered as

an enforceable California judgment.

A1: True, generally. False, in the sense that costs are discretionary, when a party

recovers other than monetary relief.

A2: True generally. False, if they are not “reasonably helpful to the trier of fact.”

CCP ' 1033.5.

A3: True generally. False, in the absence of the other elements: (2) necessity for

private enforcement; (3) burden on the plaintiff; and (4) number of people

benefitting from result. Serrano.

A4: False generally, because each party normally pays their own fees. True, if the

costs include fees (by statute).

A5: True, generally. False, in the sense that this is a matter of judicial discretion.

A1: False, generally. True in certain instances, such as orders involving

reclassification, judicial disqualification, personal jurisdiction, and forum non

conveniens.

A2: True, generally. False, regarding an issue of law that does not involve only

the case at hand, presents a significant issue of widespread importance, and

it would facilitate the public interest to decide the issue. Cedars-Sinai.

A3: True in California. False, in federal court where class action appeal is

discretionary.

A4: True in California. False in federal court, where pre-judgment review is

discretionary.

A5: True in California. False in federal court, where one may obtain an extension

(up to an additional thirty days), upon a showing of excusable neglect.

A6: False in California. True in federal court, absent the filing of a supersedeas

bond after the brief period for post-trial motions expires.

A7: True in the most general sense. False, in the sense that the error must usually

be prejudicial.

A1: True generally. False, however, when it codifies case law, or presents new

procedural or evidentiary rules.

A2: True generally. False, however, when it yields a new rule on the general

administration of justice, or would unfairly undermine the reasonable

reliance of parties on the previously existing state of the law. Newman.

A3: False generally, because of California’s primary rights approach to res

judicata. Possibly true, given the degree to which most state cases appear to

actually apply the wrong rule. The one thing that is clear is: ‘[N]o generally

approved and adequately defined system of classification of primary rights

exists.’ Boeken.

[3] MULTIPLE CHOICE REVIEW

Chose the correct answer. When more than one option may be correct, choose the best answer.

CHAPTER 1: LEGAL TERRAIN

1-1. Federal law governs a California case, when the state judge is:

(a) adjudicating a case arising under federal substantive law;

(b) adjudicating a case arising under federal procedural law;

(c) exercising concurrent subject matter jurisdiction;

(d) presiding over a state claim modeled after federal law.

1-2. An unpublished case may:

(a) be cited;

(b) be cited, if it would resolve an issue in the present case;

(c) not be cited;

(d) not be cited, if decided by another jurisdiction.

1-3. The California Rules of Court:

(a) trump the Code of Civil Procedure, when they conflict;

(b) are trumped by a judge’s local policies, when they conflict;

(c) preempt a county-wide rule, when they conflict;

(d) provide that all Judicial Council forms are mandatory.

CHAPTER 2: JURISDICTION

2-1. Subject matter jurisdiction must be pleaded in:

(a) all state and federal complaints;

(b) federal, but not state complaints;

(c) state, but not federal complaints;

(d) state complaints alleging unlimited but not limited jurisdiction.

2-2. A state case may be reclassified when:

(a) the combined amount of the complaint and cross-complaint is greater than $25,000;

(b) the court, but not a party, determines it should be reclassified;

(c) the Appellate Division of the Superior Court hears an appeal;

(d) the original complaint is for less than $25,000, and the cross-complaint is for more than

$25,000.

2-3. Concurrent subject matter jurisdiction applies when:

(a) a limited civil case alleges facts which would trigger a federal civil rights claim;

(b) P’s case alleges a malpractice claim involving federal patent law;

(c) P alleges a novel or complex state law claim in federal court;

(d) P, in good faith, claims an amount for less than $75,000.01.

2-4. Personal jurisdiction over a non-resident D depends on satisfying:

(a) either state or federal law;

(b) neither state or federal law;

(c) *both state and federal law;

(d) specific and general jurisdiction.

2-5. Personal jurisdiction over a non-resident D is satisfied in CA when:

(a) D receives actual notice of the law suit;

(b) D’s spouse is served with process;

(c) D targets all states on the US West Coast, and its product harms a CA P;

(d) D places its product into the stream of commerce, and it harms the P in CA;

2-6. A due diligence attempt to serve D is required:

(a) when attempting to serve a corporation;

(b) *as a condition precedent to substituted service on an individual in a CA state court;

(c) as a condition precedent to substituted service on an individual in a CA federal court;

(d) in order to seize D’s property in a CA tort action.

CHAPTER 3: VENUE

3-1. The local action rule:

(a) is associated with actions involving real property;

(b) was deleted from both the state and federal venue statutes;

(c) is triggered by contract actions only;

(d) is triggered by tort actions only.

3-2. California’s default venue rule:

(a) is that D should be sued where he resides;

(b) generally defeats a special venue rule;

(c) is the presumption which favors P’s residence;

(d) is that venue is determined by party choice.

3-3. Venue for corporations and associations is in the country where:

(a) the contract was made;

(b) the contract was performed;

(c) the breach occurred;

(d) all the above.

3-4. A mixed action is where:

(a) the California Superior Court can transfer a case to a state court in another state;

(b) the California Superior Court can transfer a case to federal court in California;

(c) more than one county constitutes proper venue;

(d) a case must be transferred from one country to another.

3-5. In forum non conveniens (FNC) analysis:

(a) public interest factors necessarily trump private interest factors;

(b) no single factor is dispositive;

(c) the case will be dismissed if D agrees to not to raise any defense in the new forum;

(d) a general appearance waives the option of filing a FNC motion.

CHAPTER 4: CHOICE OF LAW

4-1. State-to-state choice of law issues are:

(a) mostly procedural law differences;

(b) not based on substantive law differences;

(c) relatively uniform due to state court application of the place-of-the-wrong test;

(d) driven primarily by an interest analysis.

4-2. California tort-based choice of law decisions:

(a) do not impact class action certification, because certification ignores the merits;

(b) does impact class action certification, because certification focuses on the merits;

(c) apply a three-part test that includes a determination of whether the conflict is true;

(d) apply a three-part test that focuses on a conflict in public policy.

4-3. California contract-based choice of law decisions:

(a) whether the chosen state has a substantial relationship to the parties or their transaction;

(b) ignores whether the chosen state has a substantial relationship, to facilitate party choice;

(c) is not relevant because the judge applies CA substantive law in a CA case;

(d) supplies the Restatement approach to a contract that is silent regarding choice of law.

CHAPTER 5: PLEADING BASICS

5-1. A procedure prior to filing a lawsuit is required when:

(a) suing for any construction defect;

(b) suing a governmental entity;

(c) suing a health care service provider for any reason;

(d) suing a restaurant for food poisoning.

5-2. Pleading requirements in California:

(a) require less detail, because the D presumably knows he has defrauded the P;

(b) require less detail for a statutory claim, because the statute embodies public policy;

(c) require more detail when seeking personal injury damages than for contract damages;

(d) include stating a fact to support every prima facie element of P’s complaint.

5-3. A Separate Statement of Damages is required in:

(a) all cases except where punitive damages are sought;

(b)

(c) California wrongful death cases;

(d) both state and federal wrongful death cases.

5-4. Punitive damages:

(a) limitations apply at the pleading, discovery, and trial stages of a California lawsuit;

(b) amounts may be stated in the complaint in both limited and unlimited cases;

(c) amounts must be stated in the Civil Case Cover Sheet;

(d) can never be obtained from a health care service provider.

5-5. A general demurrer:

(a) attacks only the face of the complaint, without inquiring into the merits;

(b) attacks both the face of the complaint, and matters which may be judicially noticed;

(c) is a pleading, and is thus not subject to meet and confer requirements;

(d) differs from a special demurrer, in that the latter is no longer permitted.

5-6. Filing an answer to the complaint:

(a) is not a general appearance, just because the D asks for some affirmative relief;

(b) usually subjects a non-resident D to the court’s personal jurisdiction;

(c) operates as an affirmative defense;

(d) must specifically deny the complaint, to avoid its being a general appearance.

5-7. The statute of limitations (SOL):

(a) generally establishes a legislatively-determined filing deadline that cannot be waived;

(b) provides for either an accrual, or discovery SOL, but not both;

(c) can be tolled only by another statute;

(d) is like a statute of repose, because both provide deadlines for filing a law suit.

5-8. Amendments:

(a) should not be liberally granted in cases involving public policy violations;

(b) depend on the relation back device, regardless of whether the SOL has expired;

(c) liberally granted, may thus avoid an admission in the prior pleading, with no explanation;

(d) are granted when P has the potential to cure the initial pleading’s defect.

5-9. The e-filing and e-service of court documents:

(a) may be used in all cases;

(b) may be managed via an e-filing service provider;

(c) must also be served via mail, or overnight delivery service, or fax transmission;

(d) cannot be used for any document which requires a party or attorney’s signature.

CHAPTER 6: JOINDER

6-1. “Doe” defendants:

(a) cannot be included if P could have ascertained their identity prior to filing suit;

(b) should be added in an amended complaint, rather than the original complaint;

(c) must have charging allegations plead against them in the complaint;

(d) are generally permitted in federal court in cases of mistaken identity.

6-2. A cross-complaint:

(a) is generally both permissive and compulsory;

(b) need not be answered by the P, when it is a compulsory cross-complaint;

(c) is used by a D to expand the claims or parties beyond the original complaint;

(d) is permissive if it is logically related to P’s original complaint.

6-3. Class action:

(a) damages cannot be aggregated in federal court;

(b) damages can be aggregated in state court;

(c) cost of notice must be paid only the P in both state and federal court;

(d) opt-out procedure is not permitted in either state and federal court.

CHAPTER 7: TRUTH

7-1. Vexatious litigants:

(a) normally refers to self-represented parties;

(b) normally includes both parties and their lawyers;

(c) cannot be barred from filing a meritorious claim;

(d) cannot proceed even if they establish probably cause for the suit.

7-2. The lawyer’s signature on a pleading means that she:

(a) investigated the case before filing it;

(b) subjectively believed the case was meritorious before filing it;

(c) marshaled her evidence before filing it;

(d) is not subject to a sanctions motion for filing a frivolous pleading.

7-3. The safe harbor period:

(a) once started, immediately results in sanctions;

(b) once ended, immediately results in sanctions;

(c) must precede the filing of a sanctions motion;

(d) must follow the filing of a sanctions motion.

7-4. Anti-SLAPP motions:

(a) cannot be on an ongoing legislative, executive, or judicial proceeding;

(b) must be based on an ongoing legislative, executive, or judicial proceeding;

(c) may be based only activities related to litigation;

(d) may be based on any proceeding authorized by law.

7-5. Anti-SLAPP motions:

(a) may be filed at anytime in a lawsuit;

(b) must be filed early in a lawsuit;

(c) may be appealed only if granted;

(d) may be appealed only if denied.

7-6. Anti-SLAPP motions:

(a) cannot be defeated in both public interest and commercial speech cases;

(b) may be defeated in both public interest and commercial speech cases;

(c) apply to ordinary litigation tactics, to deter frivolous actions;

(d) apply to arbitration proceedings.

7-7. Regarding California’s anti-SLAPP motion, the Ninth Circuit federal bench:

(a) uniformly disapproves the motion;

(b) approves in some but not all cases;

(c) has not articulated any conflict with FRCP 8’s plausibility pleading requirements;

(d) has not articulated any conflict with FRCP 56’s summary judgment requirements.

CHAPTER 8: CASE MANAGEMENT

8-1. Re case management:

(a) trial judges do not assess alternative dispute resolution processes;

(b) the parties do not have to submit a Case Management Statement, if discovery is ongoing;

(c) re motions for continuance, litigation on the merits trumps administrative timeline goals;

(d) re motions for continuance, administrative timeline goals trump litigation on the merits.

8-2. The parties:

(a) will rarely, if ever, obtain a continuance to try the case;

(b) will normally obtain a continuance to try the case;

(c) must meet and confer before the Case Management Conference;

(d) must meet and confer after the Case Management Conference;

CHAPTER 9: MOTION PRACTICE

9-1. Motions:

(a) consist of a notice, the motion, and P& As in support of the motion;

(b) consist of just the notice and P& As in support of the motion;

(c) require 16 calendar days minimum notice;

(d) require 5 court days minimum notice, when mailed.

9-2. The hearing on a motion:

(a) normally requires counsels’ personal appearances;

(b) can be telephonic or in person;

(c) cannot be avoided by the judge;

(d) cannot be ex parte, with shortened notice less than provided by statute.

9-3. California’s motion for reconsideration:

(a) may be brought on multiple occasions, if needed to prevent manifest injustice;

(b) should be in writing, when there are no new facts or law to support it;

(c) is made by the judge;

(d) must be based on new facts or law.

CHAPTER 10: DISCOVERY

10-1. Initial core disclosure at the discovery stage:

(a) does not generally apply in federal courts in California;

(b) does not generally apply in California;

(c) is constitutionally required in federal courts in California;

(d) is constitutionally required in state courts in California.

10.2. Objections in a deposition:

(a) are limited to 25 over a seven-hour period;

(b) are limited to 35 over a seven-hour period;

(c) as to form of question, admissibility, and vagueness need not be made, to preserve;

(d) to form of question, admissibility, and vagueness must be made to preserve.

10-3. Privacy rights are:

(a) constitutionally based;

(b) the subject of an Evidence Code provision;

(c) available to corporations;

(d) normally trumped by the filing of a law suit.

10-4. Work product is:

(a) not discoverable;

(b) discoverable in most circumstances;

(c) discoverable in limited circumstances;

(d) either conditional or qualified.

10-5. An attorney’s work product:

(a) must be written to be protected;

(b) cannot be written to be protected;

(c) is never subject to discovery;

(d) is subject to discovery in very limited circumstances.

10-6. Prior witness statements are:

(a) always absolutely protected from discovery;

(b) always conditionally protected from discovery;

(c) generally not discoverable, because they are subject to a deposition;

(d) discoverable in some circumstances.

10-7_. When your adversary inadvertently produces privileged information, you should:

(a) do nothing;

(b) stop reading it;

(c) contact the trial judge for a resolution of what to do;

(d) destroy it.

10-8. California’s “Rule of 35” is applied:

(a) in limited cases to authorize only one deposition;

(b) in unlimited cases to authorize only one deposition;

(c) without reference to the number of depositions in either limited or unlimited cases;

(d) to limit the number of form interrogatories.

10-9. Upon receiving incomplete unverified responses to your discovery request, you should:

(a) not meet and confer with the submitting party’s attorney;

(b) file a motion for further answers within 45 days;

(c) file a motion for further answers within 45 days;

(d) demand verification.

10-10. A state court mental examination:

(a) is easier to obtain than a physical examination;

(b) may rely on non-standard testing;

(c) is not permitted to assess the pain and suffering P claims in his complaint;

(d) is permitted to assess the pain and suffering P claims in his complaint;

10-11. One must supplement one’s prior discovery responses:

(a) rarely in federal court;

(b) rarely in state court small claims cases;

(c) in both state and federal court when the prior response was wrong;

(d) in both state and federal court, only when the prior response was wrong.

10-12. Discovery sanctions:

(a) require tardiness to terminate the law suit;

(b) do not require willfulness to terminate the law suit;

(c) require willfulness to terminate the law suit;

(d) do not require a “misuse” of the discovery process.

10-13. California discovery:

(a) generally limits P’s ability to inquire into D’s assets;

(b) does not limit P’s ability to inquire into D’s assets, in punitive damage cases;

(c) generally places the burden of producing electronic discovery on the asking party;

(d) generally shifts the burden of paying for electronic discovery to the asking party.

CHAPTER 11: NON-TRIAL DISPOSITION

11-1. Contractual arbitration:

(a) is not favored under the Federal Arbitration Act;

(b) results in a petition to the judge when a party files a law suit;

(c) is identical to judicial arbitration, when the parties agree to judicial arbitration;

(d) is a basis for Federal Question subject matter jurisdiction in federal court.

11-2. Whether a claim is subject to arbitration:

(a) is usually determined by the merits of the dispute;

(b) is usually determined by reference to the Federal Arbitration Act;

(c) is usually determined by the arbitrator;

(d) is usually determined by the trial judge.

11-3. Class arbitration:

(a) is not permitted when the arbitration clause does not mention it;

(b) is permitted when the arbitration clause does not mention it;

(c) is usually unconscionable;

(d) is never permitted when there is a difference in bargaining power.

11-4. Mediation:

(a) may not be a condition precedent to litigation;

(b) is comparable to arbitration because both result in a disposition on the merits;

(c) is usually insulated from judicial review;

(d) is subject to judicial review.

11-5. A valid default judgment results from:

(a) lack of proper notice ;

(b) lack of jurisdiction;

(c) not responding to the complaint, followed by not complying with discovery obligations;

(d) not responding to the complaint, or not complying with discovery obligations.

11-6. A settlement:

(a) bar the judicial power to continue with the resolution of issues in the action;

(b) triggers the judicial power to continue with the resolution of issues in the action;

(c) cannot conceal the amount from public scrutiny;

(d) dispenses with the need to give notice of the settlement to the court.

11-7. A section 998 offer of judgment:

(a) can be for any amount, without judicial scrutiny;

(b) can be made jointly to multiple parties in most cases;

(c) does not include attorney’s fees;

(d) includes both attorney’s fees and expert witness fees.

11-8. A good faith settlement:

(a) is subject to judicial scrutiny;

(b) is not subject to judicial scrutiny;

(c) need not consider the D’s likely percentage of liability;

(d) depends directly upon D’s actual percentage of liability.

11-9. A dismissal of P’s law suit:

(a) may not be undertaken, to avoid a pending involuntary dismissal;

(b) is generally permitted, to avoid a pending involuntary dismissal;

(c) can occur at the point where a year has expired since the case was filed;

(d) cannot occur before five years from the date of filing.

11-10. Summary judgment:

(a) can be obtained only by negating the opposing party’s claim or defense;

(b) can be obtained when a state D has mailed notice 75 calendar days before the hearing;

(c) requires a Separate Statement in California cases;

(d) is a favored method for resolving cases in both state and federal courts.

CHAPTER 12: TRIAL

12-1. The right to jury is determined by:

(a) the U.S. Supreme Court for both state and federal courts;

(b) the Seventh Amendment, as it applies to state proceedings;

(c) a state judge, who may decide the entire case when equitable and legal issues overlap;

(d) the parties prior to a case being filed.

12-2. The overall jury pool, that will serve in a given period in various courts:

(a) will not contain those who were granted a work hardship before reporting for duty;

(b) will usually be drawn from sources such as the local telephone book;

(c) must be a representative cross-section of the community;

(d) need not be a representative cross-section of the community in most cases.

12-3. Voir dire:

(a) is the method for implementing the right to an impartial jury;

(b) is a guaranteed right, under the Sixth Amendment of the federal Constitution;

(c) is limited when one is challenging a juror for cause;

(d) is unlimited when one is exercising peremptory challenges.

12-4. One may successfully attack peremptory challenges:

(a) which are based on race, gender, and sexual orientation—in all courts;

(b) which are based on race, gender, and sexual orientation—in some but not all courts;

(c) when the judge has correctly denied a challenge for cause;

(d) when the judge has incorrectly denied a challenge for cause.

12-5. One may attack a verdict for lack of substantial evidence:

(a) via a state court motion for nonsuit;

(b) via a delayed demurrer in state court;

(c) if one has first made a pre-verdict motion for judgment in state court;

(d) via judgment notwithstanding the verdict in state court.

12-6. Instructions:

(a) need not be given, in either system, when no party has asked for them to be given;

(b) must be given, in both systems, even if no party has asked for them to be given;

(c) on proximate cause must be given in state negligence case involving multiple Ds;

(d) must be drawn from the CACI, but cannot be specially written by the trial lawyer.

12-7. When there are multiple Ds in a trial:

(a) they can always bring a second suit against a settling D, who did not pay her share;

(b) they normally pay their respective shares of non-economic damages;

(c) if one or more is insolvent, the others are not jointly liable for P’s economic damages;

(d) the same damage allocation rules apply, when their liability is based on strict liability.

12-8. Punitive damages in state cases:

(a) are not limited;

(b) are limited by the federal Constitution;

(c) may not exceed a 9–1 compensatory-to-punitive damage ratio;

(d) must be bifurcated from the compensatory damage phase, so that two juries can decide.

12-9. The Motion for Relief from Judgment:

(a) cannot be based on a mistake;

(b) is premised upon mistake, inadvertence, surprise, or excusable neglect;

(c) is appropriate, when the P’s attorney has missed the statute of limitations;

(d) is inappropriate, when counsel is at fault, rather the client.

CHAPTER 13: SECURE & ENFORCE JUDGMENTS

13-1. Attachment:

(a) must be sought on a noticed basis;

(b) must be sought on an ex parte basis;

(c) may be used for torts and contract cases;

(d) may be used for jurisdictional or security of judgment purposes.

13-2. TROs and preliminary injunctions:

(a) differ in terms of length of duration;

(b) differ primarily in that one is an injunction and the other is not;

(c) can be used only in domestic violence cases;

(d) depend only on whether P has a likelihood of succeeding on the merits.

13-3. Contempt of court:

(a) can apply to a false statement made by an attorney to a judge;

(b) cannot apply to a false statement made by an attorney to a judge;

(c) is civil in nature, when an attorney disrespects the court;

(d) is criminal in nature, when a penalty can be avoided by compliance with an order.

13-4. Levy and execution:

(a) are methods for collecting on a judgment;

(b) are methods for bringing suit on a judgment;

(c) are methods for obtaining a stay of execution;

(d) can seek all property a judgment debtor owns.

13-5. Sister state judgments:

(a) may be enforced in California, if rendered elsewhere by a court with jurisdiction;

(b) may not be enforced in California, if rendered elsewhere by a court with jurisdiction;

(c) are not subject to federal laws such as the U.S. Constitution’s Full Fait & Credit Clause;

(d) immediately become enforceable upon registration in California.

CHAPTER 14: COSTS AND FEES

14-1. The prevailing party is entitled to:

(a) neither costs nor attorney’s fees;

(b) costs;

(c) costs, but not fees;

(d) fees, but not costs.

14-2. Authorized costs include:

(a) filing fees and ordinary witness fees;

(b) expert’s fees and investigation expenses;

(c) expenses that are not convenient or beneficial to trial;

(d) postage, telephone, and photocopying charges.

14-3. Attorney’s fees may be recovered from an adverse party:

(a) via a loadstar calculation that multiplies actual hours worked times actual fees charged;

(b) when the plaintiff business entity is represented by in-house counsel;

(c) are not recoverable under the state and federal default rule;

(d) are recoverable under the state and federal default rules.

14-4. Attorney’s fees:

(a) must be reciprocal, that is, awarded to the prevailing party in all cases;

(b) may not be reciprocal, that is, awarded only to the prevailing party in any case;

(c) may not be awarded by private party agreement;

(d) may be awarded by private party agreement.

CHAPTER 15: APPELLATE REVIEW

15-1. Writs:

(a) differ from appeals, in the sense that each is filed at a different stage of the lawsuit;

(b) address extraordinary post-judgment orders;

(c) must be filed under CCP § 904.1 and § 904.1 (the appellate jurisdiction statutes);

(d) are taken from final judgments.

15-2. Appeals:

(a) may raise new matter, including when an appellant’s argument was not raised below;

(b) courts have jurisdiction, based on statute, but not judge-made bases for review;

(c) are not subject to California’s one final judgment rule;

(d) are subject to California’s one final judgment rule.

15-3. Collateral order appeal:

(a) is not generally available in California;

(b) is not generally available in California;

(c) is not generally available in a California federal court;

(d) is automatically available in a federal court class action denial.

15-4. An appeal is timely if:

(a) the usual 60-day period is extended by agreement of the parties;

(b) based on prejudicial error;

(c) filed within 60 days after the clerk mails “Notice of Entry” of judgment;

(d) filed within 180 days after the clerk mails “Notice of Entry” of judgment.

15-5. The standards of review:

(a) exclude the de novo and deferential abuse of discretion standards;

(b) include the de novo and deferential abuse of discretion standards;

(c) permit reversal when there is any error;

(d) permit reversal when there is no error.

CHAPTER 16: PRIOR SUIT

16-1. Stare decisis:

(a) is rarely followed in cases involving statutory construction;

(b) is generally followed in cases involving statutory construction;

(c) applies to both concurring and dissenting opinions;

(d) includes dicta.

16-2. Retroactive applicability:

(a) is given to statutes, to correct past injustices;

(b) is given to cases that are not finally resolved;

(c) is not given to statutes that codify existing law;

(d) is never given to new case law.

16-3. Preclusion applies to:

(a) res judicata and collateral estoppel in some but not all cases;

(b) bars a case which involved at least one primary right that P litigated;

(c) cannot apply when the first hearing involves an administrative claim;

(d) either state or federal judgments, but not both.

[4] MULTIPLE CHOICE—ANSWER KEY:

1-1. a

2-1. b

3-1. a

4-1. d

5-1. b

6-1. c

7-1. a

8-1. c

9-1. a

10-1. b

11-1. b

12-1. c

13-1. d

14-1. b

15-1. a

16-1. b

1-2. b

2-2. d

3-2. a

4-2. c

5-2. d

6-2. c

7-2. a

8-2. c

9-2. b

10-2. c

10-11. c

11-2. d

12-2. c

13-2. a

14-2. a

15-2. d

16-2. b

Last rev: 05/11/14

1-3. c

2-3. a

3-3. d

4-3. a

5-3. c

6-3. b

7-3. c

9-3. d

10-3. a

10-12. b

11-3. a

12-3. a

13-3. a

14-3. c

15-3. b

16-3. a

2-4. c

3-4. c

2-5. c

3-5. b

2-6. b

5-4. a

5-5. a

5-6. b

5-7. d

7-4. d

7-5. b

7-6. b

7-7. b

10-4. c

10-13. a

11-4. c

12-4. b

13-4. a

14-4. d

15-4. c

10-5. d

10-6. d

10-7. b

11-5. d 11-6. b

12-5. d 12-6. a

13-5. a

15-5. b

5-8. d

5-9. b

10-8. a 10-9. d

11-7. c 11-8. a

12-7. b 12-8. b

10-10. c

11-9. a 11-10. c

12-9. b

![[1] true and false quiz](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/009087440_1-15af11b43336a062473c28407dd01f43-768x994.png)