The economics of arms trade and arms control

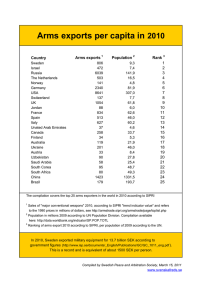

advertisement

Dr Maria Garcia-Alonso University of Kent Summer School, 2009 On arms trade: Paul Dunne (UWE) Keith Hartley (University of York) Paul Levine (University of Surrey). Ron Smith (Birckbeck College) On terrorism: Todd Sandler (University of Texas) and co-authors. Get you interested in the economics of arms trade and conflict. Give you the sources of information in case you want to know more. Provide an example of how economic theory can be used to model and understand complex problems in simple way even when the topics at hand a bound to involve judgements of value we might not even be aware of! 1. The arms trade facts: a bit of history. The Cold War The Post Cold War Era 2. Regulation of arms trade in the UK. 3. Arms trade data. 4. A model of the arms trade. 5. What can we learn from the arms trade literature? 6. The New Post September 11th challenges and asymmetric conflict. SECURITY PERCEPTION: FIRMS OWNED BY STATE EXPORTS TO ALLIES ONLY US USSR EXPORTS Arms race between main producer countries. EXPORTS US ALLIES USSR ALIES CHANGES IN SECURITY PERCEPTION: Security (Domestic Procurement, Global Exports). CHANGES IN INDUSTRY STRUCTURE: Consolidation through 90s merger wave: 5 largest firms now account for 44% of market. More openness: joint venture, semi-open tenders. More independence: no longer government controlled. BUT: Maintaining domestic defence industry still seen as strategic: national champions. Heavily regulated and supported. Not so open (exemption to the General Procurement Agreement). Not as concentrated as other industries of similar characteristics. GOVERNMENTS FACE CONFLICTING INTERESTS: security versus profits trade off when maximizing national welfare. EVOLUTION OF ASYMETRIC INFORMATION : Nationally between governments and their national champions: Efficiency levels? Exported quality? Target clients? What use? Internationally between governments and firms: Quality? Security concerns? Target clients? What use? POST COLD WAR ARMS TRADE STRUCTURE RUSSIA US REST OF THE WORLD EXPORTS CREDIT GUARANTEES DEPARTMENT UKTI DEFENCE & SECURITY ORGANISATION (UKTI DSO) http://www.ecgd.gov.uk/ formerly Defence Export Services Organisation. belongs to UK Trade & Investment (UKTI): http://www.dso.uktradeinvest.gov.uk/: works closely with industry and the MoD to promote UK equipments, products and services in the best possible way. EXPORT CONTROL ORGANIZATION belongs to BIS=BERR + DIUS http://www.berr.gov.uk/whatwedo/europeandtrade/strategic-exportcontrol/index.html Relevant policy papers: Defence Industrial Strategy, Defence White Paper, 2005. Defence Industrial Policy, MOD policy papers , paper no 5. Export Credits Guarantee Department: Annual Review and Resource Accounts. Aimed at coordinating policies of supplier and recipient states Acknowledge a need for coordination and harmonization of national controls. Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR). Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) Australia Group (chemical and biological weapons) Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies (includes most cold war adversaries). EU’s Common Rules Governing Control of Exports of Military Technology and Equipment. Transparency in arms transfers: as of January 2008, 31 states had published at least 1 report on arms exports as opposed to 6 in1998. Best data source is the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Arms Transfers Database (http://www.sipri.org/). The volume of international arms transfers peaked in 1982. Following the end of the cold war there was a steady decline in global arms transfers; they reached their lowest point in 2002, when transfers amounted to only 38 percent of their cold war high. Since 2002 there has been a more steady increase in transfers. 30 25 20 15 SIPRI TIV 10 5 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 0 Figure 1. The trend in transfers of major conventional weapons, 1999–2008 The bar graph shows annual totals and the line graph shows the five-year moving average, they give an idea of volume of transfer of major weapon systems. Source: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database, <http://armstrade.sipri.org>. supplier % share of global arms exports Total number of recipients FIRST SECOND THIRD US 35 77 TAIWAN 9% EGYPT 8% JAPAN 8% RUSSIA 26 47 CHINA 44% INDIA 23% IRAN 4% GERMANY 7 56 TURKEY 14% AUSTRALIA 11% SOUTH KOREA 7% FRANCE 7 55 UAE 21% PAKISTAN 12% TURKEY 11% UK 6 44 CANADA 18% US 12% TURKEY 10% supplier % share of global arms exports Total number of recipients FIRST SECOND THIRD US 31 69 SOUTH KOREA 15% ISRAEL 13% UAE 11% RUSSIA 25 46 CHINA 42% INDIA 21% ALGERIA 8% GERMANY 10 47 TURKEY 15% GREECE 13% SOUTH AFRICA 12% FRANCE 8 39 UAE 32% SINGAPOU RE 13% GREECE 12% UK 4 37 US 21% INDIA 14% CHILE 9% recipient % share of global arms imports Total number of suppliers FIRST SECOND THIRD CHINA 12 9 RUSSIA 92% FRANCE 3% UKRAINE 2% INDIA 8 14 RUSSIA 78% UZBEKISTAN GERMANY 5% 3% GREECE 5 13 US 52% RUSSIA 17% NETHERLA NDS 10% TURKEY 5 10 US 54% FRANCE 15% UK 11% SOUTH KOREA 4 10 US 67% GERMANY 11% FRANCE 11% recipient % share of global arms imports Total FIRST number of suppliers SECOND THIRD CHINA 11 6 RUSSIA 92% FRANCE 3% UKRAINE 2% INDIA 7 11 RUSSIA 71% UK 9% ISRAEL 6% UAE 6 13 US 54% FRANCE 43% GERMANY 1% SOUTH KOREA 6 8 US 73% GERMANY 12% FRANCE 9% GREECE 4 13 GERMANY 31% US 24% FRANCE 24% Our objective now is to construct an economic model of the arms trade. First thing to do is to choose sensible modelling assumptions to provide a good fit for the stylized facts we have already seen: 1. Agents?: Governments, firms... 2. Objectives? Welfare maximization (definition?), profit maximization (market structure?)...this will determine possible strategic interactions. 3. Choice variables?: Procurement levels, exports, quality, controls... 4. Timing? This will depend on commitment power, unless it is all clear go for simultaneous decision making. Equilibrium concept? 5. Uncertainty? Nash Equilibrium: a set of strategies such that each strategy is the best response (payoff maximizing) to the other player’s strategy (suitable for simultaneous choice decisions/games). We solve finding the intersection points of best response functions. Subgame Perfect Equilibrium - a set of strategies that satisfies both the Nash and credibility conditions (suitable for sequential decisions). We solve using backwards induction. Country 2 Country 1 Procure more weapons Do not procure more weapons Procure more weapons 2,2 4,1 Do not procure more weapons 1,4 3,3 Country 2 Country 1 Procure more weapons Procure more weapons Do not procure more weapons Do not procure more weapons 2,2 4,1 1,4 3,3 Pareto Optimum (PO) Nash Equilibrium(NE) Country 2’arms Country 1’s best response function NE Country 1’s arms Country 2 Country 1 Transfer nuclear technology Transfer nuclear technology Do not transfer 1,1 2,0 0,2 3,3 Do not transfer Country 2 Country 1 Transfer nuclear technology Transfer nuclear technology NE Do not transfer 1,1 2,0 0,2 3,3 NE and PO Do not transfer Country 2 (does not care) Country 1 Transfer nuclear technology Transfer nuclear technology Do not transfer 1,1 2,0 0,2 3,0 Do not transfer Country 2 (does not care) Country 1 Transfer nuclear technology Transfer nuclear technology NE Do not transfer 1,1 2,0 0,2 3,0 Do not transfer 1. Government chooses exports subsidy to maximize welfare: Welfare (exports, subsidy). 2. Exporter chooses exports to maximize profits: Profit (exports, subsidy) SPE by backwards induction: (2) ∂ Profit/ ∂ domestic exports=0 (1) (∂W/ ∂ s)+ (∂W/ ∂exports) (∂exports/ ∂s)= 0 Exports foreign firm Domestic firm’s best response function NE in second stage Exports domestic firm Public procurement with two way international trade. Governments impact on market structure. Firms are prices setters in the exports market. Non producer countries involved in regional conflict. Model’s Objectives: Impact of post-cold war changes on market structure. 1. MoD in producer countries take domestic procurement decisions: quality, quantity, price and number of domestic varieties/firms, given the export control structure and their budget. 2. All firms set international prices in a monopolistic competition fashion. 3. Importer countries make imported procurement decisions. Non producers also make nonmilitary consumption decisions. The model is solved for the Subgame Perfect Equilibrium and calibrated using sensible data. 1 N n S wn 1 w N n w q j d j 1 w 1 w u j m j . j n 1 j 1 n G pjd j j 1 N Pm . j n 1 j j j p j d j Pj x j C j . C j F aq j c d j x j . Military Capability: 1 N Si N u j m j ;i a, b. j 1 Ratio form Contest Success Function: a Sa pa . m m a Sa b Sb m Difference form CSF: pa 1 1 exp k b Sb a Sa . During the cold war arms race between main producers: an arms race is a Prisoner’s Dilemma Game, i.e., in the Nash Equilibrium countries end up stocking too many weapons, an agreement to reduce stockpiles would be a Pareto Improvement, however, both countries have incentives to unilaterally deviate from such agreement. Modelling tools: Game theory, both static and dynamic models. Collective action problems: for allies weapons are seen as a public good. After cold war, even though there is not direct arms race between main exporters, there is still a “double” Prisoner’s Dilemma game. Still, a trading country only considers the impact of exports on their own welfare (which now includes both security and export profits) and fails to consider the impact on the other countries’ welfare: negative externality. Modelling tools: New Trade theory: partial equilibrium models of oligopolistic international trade. Procurement theory: to model the relationship between governments and national champions. Subsidies: not just direct export subsidies, R&D subsidies and domestic procurement can act as indirect export subsidies. Arms exporters (and importers) would benefit from adhering to the Word Trade Organization agreement on export subsidies which prohibits the use of such policies. Although WTOs motivation is rooted on the positive impact subsidy savings for governments, in the arms trade case, a free trade agreement would also be beneficial for security: Higher export prices would lead to lower exports, and hence higher security and welfare for both exporters and importers (as regional arms races fuel imports). A cartel of weapon suppliers or increase in concentration would have the same effect but, there is a danger in encouraging some countries to try to start home production. Once quality is made endogenous in these models, there is a danger with cartels and mergers that more quality would be produced then, direct qualitative export controls become crucial, WTO is not enough! As Maggi (1999) notes multilateral institutions have an important role to play in: helping coordination; verifying violations of the agreement and inform third parties to facilitate enforcement; and promoting multilateral rulemaking procedure in place of a web of bilateral negotiations. Easier with less players Certainty Transparency helps Credible punishments are crucial Export subsidies increase the likelihood of defection from Export Control Agreements as a given deviation results in higher increases in profits. Between governments: it makes it more difficult to implement multilateral export control agreements. Between domestic government and it national champion over efficiency: will cause a decrease in exports as it will be more difficult to provide incentives for firms to behave efficiently, hence higher prices leading to lower level of exports. By importers of the quality of imported weapons or future replacement needs, it will reduce imports demand. Uncertain enemy Export controls on dual use technologies become ever more relevant. Other “players” perceptions of security often unknown. Asymmetric Payoffs for similar outcomes. Asymmetric warfare. Literature results: traditional warfare escalation may be counter productive. An increase in defence mechanisms against specific technology may just trigger a technological change by the opponent An increase in defence by a specific potential target may just encourage substitution for another softer target. fate terrorists fate targets fate terrorists fate •"technology variable. of conflict" is usually seen as a unidimensional •A higher amount of effort, translated into more or more advanced weapons, is the only is the only technological decision conflicting parties take. •Reality though does not always seem so simple. •Technological decisions seem to be multidimensional. •This results in a potential asymmetry of technologies actually being acquired. •Most likely to arise when conflicting powers are themselves asymmetrical in nature. Inertia vs “dynamism”: Having invested so much in a certain conflict technology and the industry to produce it and export, incumbent countries might find it difficult to change it. Resource availability vs resource constraint: Contestant powers' constrained resources and small share of existing wealth may actually encourage them to find new ways of fighting One defined adversary vs the “average” adversary. Perceived relative cost of war. First argument in parenthesis always refers to the strategy of the incumbent and the second refers to the contestant's strategy: Pa ( A, D)= probability that incumbent has of winning if they attack and contestant defends. t ea Pa ( A, D) t eb ea ea Pa ( D, A) t eb ea ea Pa ( A, A) eb ea Pa ( D, D) status quo incumbent share sa 1- sb represents the entrenching advantage. t is the technology location of the contestant. ea and eb represent the incumbent and contestant's effort respectively. Stage 1: Incumbent chooses effort. Contestant's effort is considered exogenous. Stage 2: The contestant chooses the type of technology to be acquired; the technology used by incumbent is exogenous through out the model. Stage 3: Incumbent and contestant simultaneously decide whether to adopt an attack or defense strategy. We find the Subgame Perfect Equilibrium of the above described game using backwards induction (1- )=perceived cost of conflict type (A,A), etc... a/b ATTACK DEFEND ATTACK Pa ( A, A)a A, A V Pa ( A, D)a A, D V Pb ( A, A)b A, A V Pb ( A, D)b A, D V DEFEND Pa ( D, A)a D, A V saV Pb ( D, A)b D, A V sbV Assumption 1 the incumbent enjoys the status quo and so prefers peace to attacking unthreatening challengers, this excludes unprovoked attack as a possible equilibrium (A, D). Assumption 2 defence reduces the destruction of an attack, so for the incumbent more of the prize is left under (D, A) than (A, A) Assumption 3 similarly for the challengers Assumption 4 the challengers may have an incentive to attack because the proportion of the prize left after they attack is greater than their status quo share There are two candidates for unique Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium in the conflict game (D,D) and (D,A). A decision by the incumbent to induce (D,D), that is, to prevent conflict, will become less feasible and less likely to be adopted by the incumbent, even if feasible, if differentiation by the contestant is a possibility. Asymmetric conflict may make traditional warfare prep useless in preventing conflict.