UNLV-Jallits-Saxe-Aff-2013babyjo-Round7

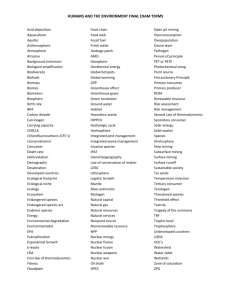

advertisement