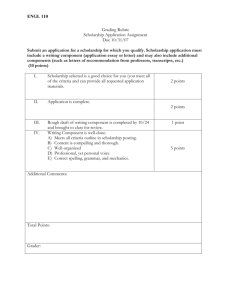

Community-engaged scholarship

advertisement

ENGAGED COMMUNITIES, CRITICAL CITIZENS: A PEDAGOGY FOR COLLABORATIVELY DEVELOPING KNOWLEDGE AND SOLUTIONS TO PUBLIC ISSUES US higher education institutions mission statements returning to civic purposes of higher education (AACU, 2008; Furco & Goss, 2001; Musil, 2011) Community-engaged scholarship recommended as a practice for achieving civic outcomes (Boyer, 1996; Campus Compact, 2011). Multiple meanings, overlapping meanings (Howard, 2011) Lack of clarity PRESENTATION GOALS What definition of community-engaged scholarship integrates the multiple understandings of this term (and related terms—e.g. public scholarship, scholarship of engagement) from the literature? What pedagogical components are repeatedly recommended by researchers and practitioners of community-engaged scholarship, public scholarship, and scholarship of engagement? PRESENTATION OUTLINE Methodology Consensus definition Six components Practical Examples UC Berkeley American Cultures Engaged Scholarship program & Cal Corps Public Service Center Critical Community-Engaged Scholarship METHODOLOGY Literature review of articles on: community-engaged scholarship public scholarship active and engaged scholarship curricular engagement and outreach and scholarship community-based research scholarship of engagement Definitions and recommendations for action COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP: AN INTEGRATION OF TERMINOLOGY METHODOLOGY “RACE-THROUGH” MaxQDA Grounded theory Coding: openaxialintegrated theory Two interpretive communities 1. Colleagues Educational research for social and racial justice 2. Community-Engaged Scholarship Practitioners Suzan Akin and Megan Voorhees from the Cal Corps Public Service Center and Victoria Robinson, head of the American Cultures Engaged Scholarship program at the University of California, Berkeley A CONSENSUS DEFINITION Community-engaged scholarship focuses on the application and collaborative development of knowledge to consequential public issues through authentic, mutually beneficial partnerships between universities and communities. It includes: 1) Scholarly investigation of real-life social problems or public issues 2) Real-life social problems and research to address these problems that are defined with or by the community 3) Community-university partnerships that are collaborative and reciprocal and have shared authority in defining success 4) Knowledge to solve or improve public issues that is collaboratively developed by universities and communities 5) The utilization of institutional resources and knowledge to solve these real-life social problems or public issues 6) Community-engaged research or projects that are related to faculty members’ research and teaching A CAVEAT… Expand on theoretical definitions of components Provide concrete example of each component in practice On the one hand… Artificial divide of a holistic and synthetic pedagogy On the other hand… Instructive device for clearly illustrating each component Will end with synthetic example COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP: COMPONENT 1 Scholarly investigations of real-life social problems or public issues Public issues could come from an array of areas Economic development to social or cultural expansion (Stanton et al., 2007) Education and the economy, agriculture and food, access to healthcare, urban revitalization, conservation of the environment, and natural resources (The Kellogg Commission, 1999). Public issues most relevant to mission, faculty scholarship, and the surrounding communities COMPONENT 1: AN EXAMPLE UC Berkeley Professor Victoria Robinson’s course: A Comparative Survey of Racial and Ethnic Groups in the U.S: Towards an Abolition Pedagogy Tools and historical background necessary engage in meaningful and informed debates about race, gender, legal status, crime and punishment in the US Tools into practice to consider questions of an abolition pedagogy Strives “create genuinely healthy, stable communities that respond to harm without relying on imprisonment and punishment.” (Critical Resistance, 2012) In collaboration with: Critical Resistance (local-and national-prison abolition community organization) Two student fellows Identified public issues: Knowledge gap the prison industrial complex (PIC) and grassroots struggles Lack of accessibility to existing PIC knowledge COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP: COMPONENT 2 Importance of who defines real-life social problems or public issues Either community-identified or collaboratively identified with university and community members COMPONENT 2: AN EXAMPLE UC Berkeley Professor William Satariano’s course: Introduction to Community Health and Human Development Collaborative syllabus development Community Advisory Board - perspectives on key public health issues Building on previous relationships…. Local health departments (Contra Costa County, Alameda County, and San Francisco) A governmental agency—The Department of Maternal and Child Health Services Two local nonprofit organizations Collaborating Agencies Responding to Disasters (CARD) Building Blocks for Kids (BB4K) Consulted on: course content, readings, in-class speakers, panel members COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP: COMPONENT 3 Community-university partnerships that are collaborative, reciprocal, and mutually beneficial Shared authority in defining success COMPONENT 3: AN EXAMPLE Satariano’s course: Introduction to Community Health and Human Development Partnership with Building Blocks for Kids (BB4K—improving the quality of life for children with health-related needs) Course learning goal: Students should be able to research and interpret US census data and apply this information to assessing and addressing factors in epidemiology BB4K writing government grant Include a needs assessment of residents in their constituency Legitimacy through a university partnership Reciprocal and mutually beneficial partnership COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP: COMPONENT 4 Collaborative production of knowledge Knowledge-generating tasks are shared with community partners and university members Everyone has a role in public problem-solving COMPONENT 4: AN EXAMPLE Robinson’s course: Comparative Survey of Racial and Ethnic Groups in U.S Establishing the knowledge gap on the prison industrial complex UC Berkeley Student Fellows in the course: David Melena and Aries Jaramillo Three members of Critical Resistance Critical Resistance Organizing experiences and familiarity with community oral histories Identified specific categories of knowledge missing from Wikipedia E.g. alternatives to incarceration, three strikes, gender responsive corrections, and racial profiling Students Collaborative working groups Researched , wrote, revised Wikipedia pages with academic standards for citations New knowledge collaboratively created and publicly available COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP: COMPONENT 5 Use of institutional resources and knowledge to solve real-life public issues Universities rich in: library access, technology, research-expertise, and knowledge Communities rich in: Practical application of theoretical knowledge Connecting university resources to community knowledge and/or issues COMPONENT 5: AN EXAMPLE UC Berkeley Art Practice course… need to check in further with professor of this course before sharing. COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP: COMPONENT 6 Course content and focus related to the faculty member’s scholarship Community-based component related to academic content of course Community-based component extends faculty member’s research and/or results in collaborative knowledge production in faculty member’s area of expertise COMPONENT 6: AN EXAMPLE UC Berkeley Professor Juana María Rodríguez’s course: Queer Theories/Activist Practices Faculty member’s scholarship: Intersection of ethnic studies and sexuality Identities transformed through language, law, culture, and public policy Spaces: Activism-in particular surrounding HIV; immigration law; and cyberspace Course content: Definitions of activism, community engagement, and social transformation Limits/possibilities various interventions—arts, law, advocacy, and direct action Community-based component Community organizations focused on HIV activism, arts, law, and advocacy Collaborative knowledge production: annotated bibliographies Extension research: other direction… research deepens course INTEGRATING COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP AND CRITICAL SERVICELEARNING: Many similarities between critical service-learning and community-engaged scholarship: Development of authentic relationships with community partners Focus on relevant social issues Integration of service or community-engagement with course content Community-engaged scholarship: A slight shift in emphasis Community-engaged scholarship: includes focus of utilizing institutional resources Critical service-learning focus on: Balancing student learning and service with the community-identified needs/issues Community-engaged scholarship focuses on: Knowledge application and the collaborative production of knowledge to solve pressing social issues. Progressive shift from locating “social problems” within communities to locating problems in our democracy BUILDING ON CRITICAL SERVICE-LEARNING “Without the exercise of care and consciousness, drawing attention to root causes of social problems, and involving students in actions and initiatives addressing root causes, service-learning may have no impact beyond students’ good feelings. In fact, a service-learning experience that does not pay attention to those issues and concerns may involve students in the community in a way that perpetuates inequality …” (Mitchell, 2008, p. 51) BUILDING ON CRITICAL SERVICE-LEARNING Critical service-learning includes unambiguous focus on social justice and the redistribution of power Community-engaged scholarship may focus on similar topics yet critical consciousness not explicitly-named Critical community-engaged scholarship Includes the six components Building on critical service learning Explicit focus on justice Development of not just knowledge, but critically-conscious knowledge Redistribution of power Democratization of classroom (not in 6 components) Valuing expertise and work of students Knowledge base that comes with bringing diverse experiences into classroom CRITICAL COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP UC Berkeley Professor Hatem Bazian: Muslims in America Partnerships Multiple off-campus community organizations: (e.g. Council on American-Islamic Relations, Asian Law Caucus, Zaytuna College, Northern California Islamic Council, Arab Cultural Research Center …) On-campus: Muslim Student Association Public issue Muslim Americans being left out of the public discourse in America Course Focus Affirm the Muslim community within the fabric of American society Document US-Muslim community narratives in systematic ways CRITICAL COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP Blurring the boundaries of university and community Course Twitter Feed Council on American-Islamic Relations tweets a link to their article on Dutch politician Geert Wilders in-class discussion topic Feedback from community organization Access to information on Muslims in America limited Bazian posts all lectures on iTunes for free download (utilize university resources) International conference, Islamophobia Production and Redefining a Global “Security” Agenda for the 21st Century Addressing public issue Students develop websites that “Document the history of Muslims in America” 45 webpages now publicly available CRITICAL COMMUNITY-ENGAGED SCHOLARSHIP Bazian’s Research Agenda to use education as a tool for empowerment to counteract the structures in place which prevent Muslim Americans from reaching their full humanity and citizenship in American life Collectively--webpages of students, policy recommendations and articles from community organizations, and online and in-person dialogue on current events deepens, shapes, and informs Bazian’s research agenda Reciprocally—twitter feeds, webpages, publicly accessible lectures, and conference sessions—are building the knowledge base on Muslims in America IN CONCLUSION Higher education institutions re-committing to civic purposes Train graduates for leadership positions with power and influence in our society (Gutman, 1987), thus crucial prepare citizens for just democratic participation Community-engaged scholarship—is frequently recommended as a practice for achieving civic-engagement outcomes (Boyer, 1996; Campus Compact, 2011). Synthesize consensus of recommendations from the literature Working definition of community-engaged scholarship with six components Possible future direction—critical community-engaged scholarship Future researchers should deconstruct AND reconstruct this definition THANK YOU Cynthia Gordon Harvard Graduate School of Education Ed.D. expected May 2013 UC Berkeley, American Cultures Engaged Scholarship Graduate Research Assistant Email: cynthia_gordon@mail.harvard.edu