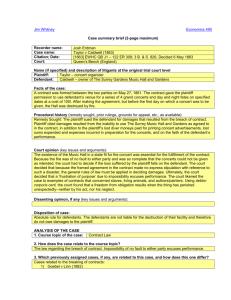

Joyce Torts Outline - A grade - anonymous

advertisement