Planet Debate Files - PS278MiddleSchoolHistory

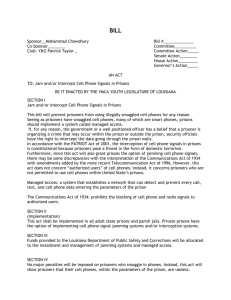

advertisement