DariaBerezhkova - Lund University Publications

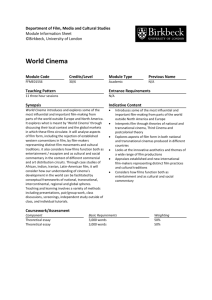

advertisement