Diapositiva 1

advertisement

The phonetic and phonologic continuity

in first language acquisition studies

María Ramírez Cruz

Máster en estudios fónicos CSIC-UIMP

Research Presentation

D. K Oller (1980):

Infant vocalizations have long been studied on the

assumption that their form reveal aspects of a

developing capacity for speech. However, we can

difference two sounds types:

- Vocalization types whose physical form differs too

from mature linguistic utterances (non speech-like).

- Infant sounds in the second half of first year of life

which are adult speech-like.

Research presentation

Aims

The purposes of this research respond to both different

wide stages :

1. To analyze methaphonological features (Oller, 1980)

between internal stages of non speech-like from 0-6

months, to show there is a continuity as it ‘s been

demonstrated by some authors (Oller, 1980). The

acoustic parameters to analyze are:

Research presentation

2. To analyze phonetic and prosody parameters from

prelinguistic stages to the first linguistic stage (first

words stage) and see if there is or not a lack of prosody

continuity between these particular stages as it’s been

postulated by some authors (Rory A. DePaolisa,,Marilyn

M. Vihman and Sari Kunnari, 2008). The parameters to

analyze are:

- Syllable duration.

- Intensity.

Research Presentation

Methodology

Longitudinal study of three Spanish children, two boys

and a girl, with Spanish as a first language, since 1

months to one year and a half.

Weekly recordings of three children’s productions in

different but constant familiar setting.

Only audio record not video (even video is more

informative but also more complex).

Research Presentation

We recorder with a Marantz PMD 620 in PCDM or *wav

formant . The sample frequency is 41KHz .

To export meaningful segments, syllabes and words for

our acoustic and phonological study.

The validation of these categories by trained

investigators (acoustic).

Compilation for creating three corpora (one per baby)

with PHON software.

Non speech-like

The vocalizations continuity in the first half of year (Oller,

1980).

These occurs in a more frequent way until 6 months.

The stages of these vocalizations can be defined taking

in account relative frequency of occurrence of sound

types at each stage:

- The phonation stage (0-1 month): QRNs “Quasiresonant Nuclei include normal phonation but not

involve any contrast between opening an closure of

the vocal tract and do not make use of the full

potential of the vocal cavity to fuction as a

resonatingf tube.

Non speech-like

- The GOO stage (2-4 month): QRN and a tendency

for velar closure.

- The expansion stage (4-6 month): FRNs “Full

Resonant Nuclei”, or vowel-like elements; SQ

“Squealing” or a highly tense pithc register; Growling

or very low-pitch; Yelling: high amplitude

nondistresss vocalization; IES: ingressive-egressive

sequences.

* Marginal babbling: consisting of sequences

in which a closure of the vocal tract is

opposed with an FRN, (Doyle, 1976, Oller,

1976).

Non speech-like

Specific methodology

These kinds of infant sounds that differ substantially

from speech, are impossible to describe in terms of

concrete phonology (plosive, fricative, high vowel…) so

we need another type of phonology and this is Oller’s

“metaphonology”, (Oller, 1980).

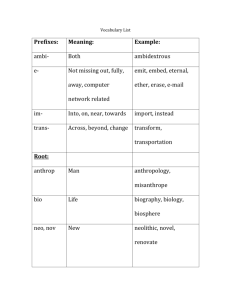

The “metaphonological features” to analyse are:

Non speech-like

- picht.

- phonation type (voice quality).

- resonance pattern.

- timing (syllabicity) .

- amplitude .

Selection criteria: Oller’s and Suneeti criteria in “Beyond

ba-ba and gu-gu: challenges and strategies in coding

infant vocalizations”, Behaviour Research Methods,

Instruments and Conmputers, 2001.

Acoustic programs CSpeech (TF32 2000), PRAAT or

Glotex for an oscillographic, spectographic, and F0

analysis to analyze Specific Aim the metaphonological

control continuity between these stages .

Non speech-like

For the study of these stages it makes no sense to use

PHON because:

- We study metaphonological objects which can be

studied only with acoustic programs to let us

describe them ( pitch, amplitude resonance).

- It’d be really hard, complex and usefulness to make

corpora with these kind of sounds and between other

reason is they have not phonological features but

metaphonological so we can’t transcribe them with

phonetic and phonologic symbols-diacritics of adult

speech-like.

Non speech-like

Bibliography

Murai, J. (1963): “The sounds of infants: their Phonemicization and

symbolization” Studia Phoonologica, 3, 18-34.

Oller, D. K. (1976): “Infant vocalizations: a linguistic and speech

scientific perspective” Miniseminar for the American Speech and

Hearing Association, Houston.

Oller, D. K (1991).: “Computational approaches to trasncription and

analysis in child phonology”, Journal for computer users in speech and

hearing, 7, 44-59

Doyle, W. J. (1976): “On the verge of meaningful speech”, Master’s

Thesis, university of Washington, Seattle.

Zlatin, M. A. (1975): “Preliminary descriptive model of infant

vocalization during the first 24 weeks: Primitive syllabification and

phonetic exploratory behavior” Final Report, Project No. 3-4014,

Grant NE-G00-3-0077.

Speech-like

The phonetic and prosody continuity between prelinguistic stages and first linguist stage.

It’s true that the adult-like production of prosody is a

difficult task for the prelinguistic infant, “requiring that

their perceptual sensitivity to elements of prosody be

translated into fine motor adjustments affecting

fundamental frequency, timing, and intensity over more

than one syllable” (Rory A. DePaolisa, Marilyn M.

Vihmanb, Sari Kunnaric, 2008).

These authors see the first control of prosody when

infants produce their first words. However, we’ll analyze

Speech-like

the syllabe structure, intensity and duration, as acoustic

parameters of prosody features, before the first words

stadium, in order to see if there is some kind of

continuity between these stages.

The pre-linguistic stages to analyse are:

- Canonical Babbling (6-10 months):

- Rigid timing characteristics of syllabification .

- Reduplicated babbling: syllables with an important

negative characteristic: its lack of substantial

variation.

Speech-like

- Variegated Babbling (10-12):

- Different consonantal and vocalic elements.

- Contrasts of syllabic stress.

- Proto-words (from 10 months): “stable child phonetic

forms with a referential meaning emerging from the

context, not a symbolic one” (Menyuk and Menn, 1979).

Others: “call sounds” (Werner and Kaplan 1984),

“prewords” (Ferguson, 1978).

First linguistic stage

First words (from 12 months)

-

-

Adult-word-based forms which reflect at least

partial awareness or understanding of the adult

meaning.

Referential and symbolic meaning in a consistent

phonetic form.

Prelinguistic-linguistic

Specific methodology

To prove the last results which confirm how phonetic and

phonologic tendencies in early speech can be seen in

babbling ( Oller, Doyle, Wieman, Ross 1976, 1980 and

Locke, 1980) we need acoustic analysis of:

- Syllable duration.

- Intensity.

Selection criteria:

Disyllables were considered candidates for inclusion if

they were separated from surrounding utterances by at

least 400 ms (following Branigan, 1979).

Prelinguistic-linguistic

Disyllables separated by less than 400ms were included if

there were clear prosodic breaks with the surrounding

speech (such as a clear inhalation to start a new breath

group).

Disyllables were included if they minimally contained

two open (vocalic) phases separated by a closed

(consonantal) phase.

Words were separated from babble following Vihman

and McCune (1994).

Disyllables that showed excessive shifts ofregister,

excessive vocal effort, creaky voice, or whisper were also

excluded.

Prelinguistic-linguistic

For the analysis we need acoustic programs like CSpeech

(TF32 2000), PRAAT or Glotex for an oscillographic,

spectographic, to analyze the prosody control continuity

between these stages .

PHON is not useful in the specific acoustic analysis but it

can help in making projects, counting different segments

and in others analysis like:

PHON utilities

1. To create three digitized corpora, one per child,

following RETAHME methodology which allow us to

record, transcribe and analyze spontaneous peech

samples in the project of a computerized database with

another investigators’s corpora.

PHON utilities (modificar)

2.

It’s the only software which gives us phonetic transcription in an

universal code, IPA, so once our corpora are ready and upload ed to

PHON database, everyone in the world can access and study them

(not whit DIME or PERLA).

PHON utilities

3. For baby’s speech transcriptions is an useful resource

the fact that PHON configuration/tools let us have the

phonetic transcription aligned with audio files and

always with the option of modify phonetic transcription

if in a new listening of the audio we think there is

another transcription ([e]> [ɛ])

PHON utilities

4. Multi-blind mode is an important PHON function for our

research.

The fact that different transcribers can listen the same

fragment and then transcribe it without other

transcriptions are available for them, give us different

approximations to babbling phonetic segments.

PHON utilities

PHON utilities

Having different transcriptions of the same babbling fragment ,

facilitate the creation of a research group where everyone can

transcribe what he considers and then the transcriptor manager by a

systematic comparation can choose the best option after having

debating.

PHON utilities

5.

The Phon function of calculating inventories of different

categories is highly useful to show us the degree of

continuity in the universal categories of language

development:

- phones.

- syllabes.

- stress patterns

It spares us the hard, tedious and time-consuming job of

counting every phone, syllabe and stress pattern, stage

by stage.

(linguistic annotation and syntax known by linguistic researches)

PHON utilities

Phone type:

PHON utilities

Syllabe type:

A phone's syllable constituent type can be specified

PHON utilities

Stress patterns:

- Unstressed vs stressed.

- Continuity of trocaic foot from babbling and in first

words.

- Which type of syllabic structure has the stress (which

phones and which possition)

PHON utilities

6. PHON search options are completely necessary for

studying the degree of continuity in baby’s linguistic

development.

PHON utilities

PHON searches (simple and complex queries) allow us to

know which segments are more frequent in syllabe

structure in every stage and in which position.

Consequently we can set comparisons between stages.

Data tiers searches

PHON utilities

- Syllabe types search show us the frequent syllabic

structure in each stage.

PHON utilities

- PhonEx:

Segmtents:

{Coronal, Stop}: this will match all cornal stops

transcribed in teh selected session.

Syllabe stress information searches

Example phonEx query ; Oral expression

{Vowel}:NoStress ;

vowels in unstressed syllabes

Phon utilities

Aligned Phones - queries stress patterns and/or aligned

phones on the Syllable Alignment tier, useful for

comparing target and actual data.

PHON utilities

- Aligned Groups- queries two tiers of choice, useful for

comparing aligned Word Groups on any tier.

- Harmony- compares target and actual utterances for

instances of vowel or consonant harmony.

- Epenthesis.

PHOn utilities

- Deletion:

PHON utilities

7. Colourful syllabic alignment is useful for codified baby’s

speech for two reasons:

To change the automatic syllabic alignment reflexing

the baby’s actual syllabic alignment:

PHON improvements

1. PHON is not sufficient for narrow babies phonetic

transcription, for example for babbling. To the difficulty

we have to use acoustic programs to find out which

segment the baby is articulating, (se suma) adding the

lack of specific symbols for transcribed this particular

phonetic.

PHON disadavantages

Even IPA PHON map has some combining diacritics

which can help in babbling transcription:

PHON disadvantages

Specific symbols,as the specific for disordered speech of

ExtIPA symbols for disordered speech (1997), are needed

for babbling transcription (Oller specific for

infraphonology:

PHON disadvantages

Another option is to include disordered symbols in PHON

IPA map because some of them can be used for babies

segments:

- (¯) for undeterminated sounds.

- (V) for undeterminated vocalic sounds (the

acoustical formants analysis shows is a vocalic sound

but it doesn’t seem to a known vowel).

Thank you so much!

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to the entire GrEP group,

the subjects, and especially to Phon and

Yvan Rose for all of his continued help.

Bibliography

Boersma, P., & Weenink, D., (2005): Praat: doing phonetics by computer

(Version 4.3.14), retrieved May, 26, 2005.

Cruttenden, A. (1970): “A phonetic study of babbling” British Journal of

Disorders of Communication, 5, 110-118.

Davis, B. L., MacNeilage, P. F., Matyear, C. L., & Powell, J. K. (2000). Prosodic

correlates of stress in babbling: An acoustical study.Child Development, 71,

1258–1270.

Halle´ , P. A., Boysson-Bardies, B., & Vihman, M. M. (1991). Beginnings of

prosodic organization: Intonation and duration patterns of disyllables

produced by Japanese and French infants. Language and Speech, 34, 299–

318.

Levitt, A. G. (1993). The acquisition of prosody: Evidence from French- and

English-learning infants. In B. de. Boysson-Bardies, S. de.Schonen, P.

Jusczyk, P. MacNeillage, & J. Morton (Eds.), Developmental neurocognition:

Speech and face processing in the first year oflife (pp. 385–398). Dordrecht:

Kluwer Academic.

Bibliography

McCarthy, D. (1952): “Organismic interpretation of infant vocalizations”,

Child Development, 23, 273-80.

MacWhinney, B., & Rose, Y., (2007): “PHON” supported by grant RO1HD051698 from NIH-NICHHD to Brian MacWhinney and Yvan Rose in

CHILDES project, 1995.

Oller, D. K (1980): “The emergence of the sounds of speech in infancy” in

Child phonology, ed. Yeni-Komshian, Grace H:, Kavanahg, James F.,

Ferguson, Charles, Academic Press, London, vol. 1.

Oller, D. K., Wieman, L. A., Doyle, W., and Ross, C. (1975): “Infant babbling

and speech”, Journal of Child Language, 3, 1-11.

Robb, M. P., & Tyler, A. A. (1995). Durations of young children’s word and

nonword vocalizations. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 98,

1348–1354

Bibliography

Rory A. DePaolisa,,Marilyn M. Vihmanb, Sari Kunnari (2008): ”Prosody in

production at the onset of word use:A cross-linguistic study”, Journal of

phonetics,36, pp. 406-422.

Vihman, M. M., & DePaolis, R. A. (1998). Perception and production in early

vocal development: Evidence from the acquisition of accent. In M. C. Gruber,

D. Higgins, K. S. Olson, & T. Wysocki (Eds.), Chicago Linguistic Society 34,

Part 2: Papers from the panels (pp. 373–386). Chicago, IL: CLS.

Yeni-komshian, Grace H:, Kavahagh, James F., Ferguson, Charles, A. (1980):

Child phonology, Academic Press, London, vol. 1.