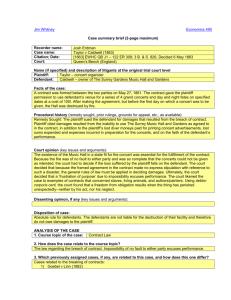

notes 2 (2012)

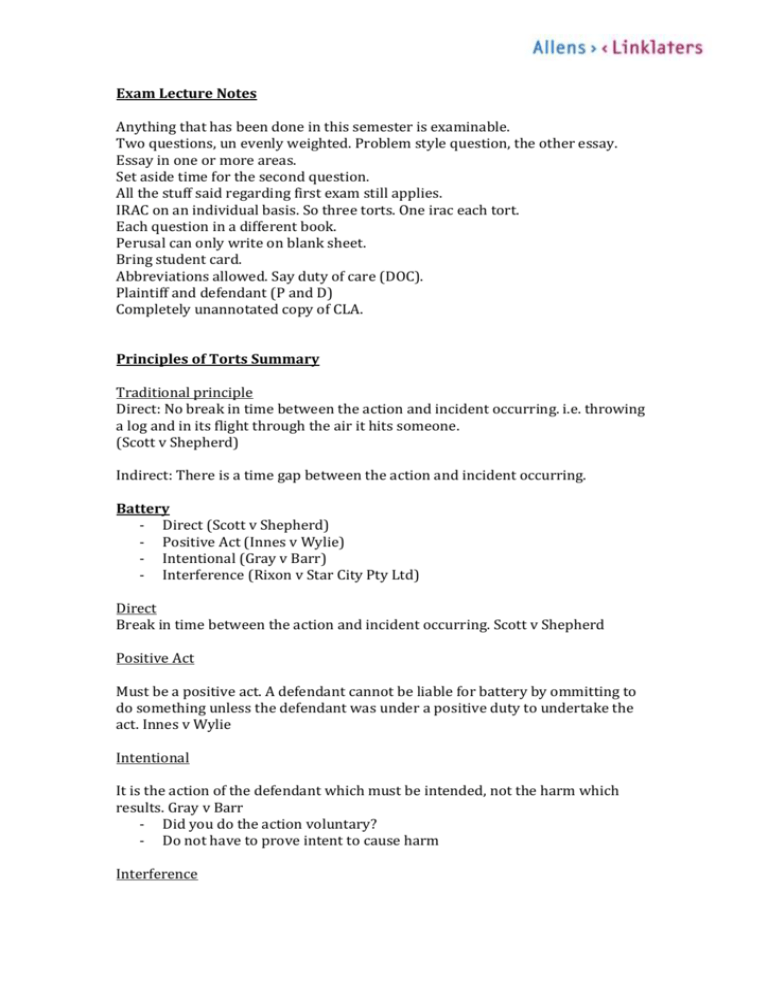

advertisement