The Pain of Abdominal Pain

advertisement

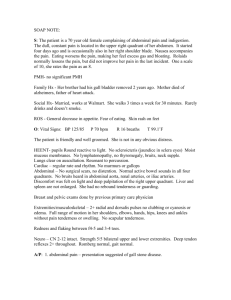

“The Pain of Abdominal Pain” Russell Cameron, M.D. New Perspectives in Pediatrics Conference Wednesday, October 21, 2015 Disclosure I have no relevant financial relationships or conflicts of interest to disclose. Objectives 1. Discuss approach to pediatric patients with functional abdominal pain 2. How to address patient and parental fears and expectations 3. Discuss when to call a surgeon and when to call a psychologist Why is this important? • About half of patients referred to pediatric GI clinics have symptoms that do not have a readily discernible cause • Knowing how to relieve the physical and emotional suffering in patients without “disease” is a necessity for every clinician Abdominal Pain • Usually stimulated by one of three pathways: – Visceral – Somatic – Referred • Variability in the experience of pain – Neuroanatomic, neurophysiologic, pathophysiologic, environmental, and psychosocial Visceral Pain • Caused by distended viscus which activates a local nerve, sending an impulse that travels through autonomic afferent fibers to the spinal tract and central nervous system • Localization of pain is difficult because there are few afferent nerves traveling from the viscera, and nerve fibers overlap • Epigastric, periumbilical, or suprapubic Somatic Pain • Carried by somatic nerves in the parietal peritoneum, muscle, or skin • Usually well localized and sharp Referred Pain • Perceived at a site remote from the actual affected viscera • Sharp, localized, or diffuse Biomedical Model • Two assumptions: 1. Any symptom can be traced back to a single cause 2. Every symptom is either “organic,” meaning there is an identifiable, objectively defined pathophysiology, or “functional,” meaning without identifiable, objectively defined pathophysiology – This dualistic approach implicitly places “organic disease” in high esteem – Functional disorders are considered less serious, psychological, or often without etiology or treatment – The biomedical model works for a broken bone or a kidney stone, but not so well when there are chronic problems such as headaches, abdominal pain, or chronic fatigue Parent’s Fears Patient’s Suffering Wrong Model Bad Experience Expectations and Frustration Imperfect Tools Imperfect Treatments SEP 16, 2009 “Misdiagnosis and Regret” • A reader who was recently found to have a rare, serious condition sent Doctor D a question about visiting one of several doctors who missed the diagnosis: – “It could be terribly awkward to have an appointment with one of them—me with all my new scars and a scary prognosis and them perhaps with their former, incorrect diagnoses of various benign conditions hanging in the air” – “I'd welcome a chance to let them know that I understand that it's impossible to get these things right instantly every time, and I have no resentment” – “But would it be better to just see a brand new doctor? Or would my former doctors want to see me? Or would they rather I melt into the ether and just let them forget it all?” • Every doctor has had that “Oh crap! It was X? I thought it was Y!” panic after finding out about a misdiagnosis. The unspoken truth is that doctors guess—a lot. Usually we make informed, educated guesses, but even good guesses can be incorrect. Unusual conditions can be hard to discover, and we often make several wrong diagnoses on the way to the right one • “Retrospectascope” - only medical instrument that produces the right answer every time • “We feel all patients demand perfection, and we work with imperfect tools and imperfect knowledge. Even the best care won't always produce the right answer—especially at the beginning. Example • Ashley is a 17-year-old was referred from the ER – Acute onset crampy abdominal pain and loose stools without blood during her first semester of college far away from home – She was upset by a separation from her high school boyfriend – Skipping breakfast and lunch to avoid having to interrupt her classes to use the rest room – Loosing weight Work Up – Screening laboratory tests – Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and Celiac serology and screening labs were normal – GI performs an EGD and colonoscopy and 24 hour pH-Impedance – All were normal Pain cont… – Sharp pains under the ribcage after meals, and the frequency and severity of the abdominal pain worsened – Unable to return to class because of worsening pain intensity – PCP sent her to the surgeon who ordered a HIDA scan – Ejection fraction was 33% (adult normal 35 to 90%) The “cure” – The surgeon removed the gallbladder – The patient had prolonged pain after surgery and was discharged on NJ tube feedings, narcotics for abdominal pain, and polyethylene glycol for constipation – She remained out of school for many months, disabled by pain and unable to eat The aftermath… • Psychiatric consult found no eating or thought disorder and criticized the gastroenterologists for requesting the consultation, stating that the request might have been motivated by the physicians’ failure to find what was wrong • The patient, family, and clinicians inadvertently co-created disability by considering only organic etiologies and avoiding the reality of the patient’s stressful experiences and functional, physiologic responses to stress, namely, IBS and functional nausea and vomiting Analysis • They approached the problem from a biomedical model and the presumption that illness must have an organic etiology • Extensive testing for diseases to explain symptoms • Each negative test result reinforced the worries and fears that something important was being missed • Focus on the mystery disease and miss recognizing the emotional impacts of separations from her family, her ex-boyfriend, and her failure to adjust to college • The patient, parent, and provider were upset and frustrated by the failure to find organic pathology Biopsychosocial Model • Engel in 1977 • Goal is to understand and treat illness, the patient’s subjective sense of suffering, rather than confining the diagnostic effort to no more than finding disease • Symptoms may develop from several different influences, not just disease, and may stem from: – – – – Normal development (infant regurgitation) Psychiatric disease (pain, conversion, factitious disorders) Impact of culture and society (uninsured) Functional disorders (symptoms are real, but there is no easily discerned disease) D.R. Fleisher, E.J. Feldman: The biopsychosocial model of clinical practice in functional gastrointestinal disorders. P.E. Hyman p. 2-6 Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 1999 Academy Professional Information Services New York 21-22 “Being human is messy and we are not that good at it” • Rather than reducing a cluster of symptoms to a single pathophysiology (reductionism), the biopsychosocial model expands the potential for understanding a problem from simultaneously interacting systems at subcellular, cellular, tissue, organ, interpersonal, and environmental levels Biomedical versus Biopsychosocial • Not versus but and… – Most clinicians include elements of both – All illnesses, organic and functional, can be managed within the framework of the biopsychosocial rather than the biomedical model • Goal - improving patients’ well-being • Difference in what is considered to be impairment and the extent to which the clinician considers the origin and remedies to that impairment • Biomedical model limits the role of the clinician to the diagnosis and treatment of disease and assumes that doing so restores well-being • Biopsychosocial model expands the meaning of the goal and the clinical process by which it is achieved – Illness is defined as the patient’s subjective sense of suffering – The goal of management is to identify the patient’s disease as well as other factors contributing to suffering – Includes an analysis of the relationship and contributions of each factor in the patient’s illness Illness Approach • Frame the conversation with the following categories: – Things we needed to know about yesterday because they are emergent and need an intervention (ASAP) – Things we want to find out about because it will significantly change our approach – Things that we will have to continue to learn about in order to make the symptoms better • This will be a process and that the process is frustrating for: – Patient because they are the one having the pain – Parent because they are watching their child have pain and feel helpless to fix it – Provider because we are having to make educated and uneducated guesses as to what could be causing the symptoms “5 symptoms of GI tract” • Abdominal pain • Nausea • Vomiting • Diarrhea • Constipation But… “2000 + potential causes” Approach • Quality, timing, location, associations, and story are important and should be used as your guide in working it up and also your guide to stopping the investigation – Build trust, show you are listening – Be nosy – Be interested • Acknowledge that this is frustrating and ask what is your greatest concern, what is your biggest fear? Approach • I use a dry erase board to document the facts of their story and then use those symptoms to help come up with a game plan that we all agree on • There are some baseline labs, stool studies, and imaging studies that we often order • Value of the physical exam – lets them know you are taking this seriously (Abraham Verghese, MD) https://www.ted.com/talks/abraham_verghese_a _doctor_s_touch?language=en#t-125798 Testing • Laboratory, radiologic, endoscopic, and ancillary evaluation – Should be individualized according to the information obtained during the history and physical examination – Most clinicians recommend the following studies as an initial screen for all patients with recurrent abdominal pain: • CBC, UA with culture, Liver enzymes, ESR, Celiac and Stool O&P • If normal, in combination with a normal physical examination, effectively rule out an organic cause in 95% of cases. – Other: Noninvasive studies and Invasive studies – Ex: • Ultrasound has gained a prominent role over the past decade because it is painless and does not involve radiation • 3 studies to investigate the diagnostic value of routine abdominal ultrasound in children with recurrent abdominal pain failed to demonstrate its utility in this clinical setting • 217 patients were evaluated and a total of 16 patients were found to have abnormalities identified by abdominal ultrasound, but in no case could the pain be attributed to the abnormality FGID: Functional Gastrointestinal Disease • • • • RAP FAP CRAP IBS • Functional Dyspepsia • Abdominal Migraines Apley • At least 1 episode per month for 3 consecutive months and severe enough to interfere with routine functioning • Affects 10-15% of school age • Up to 46% of children experience during childhood ROME III -> IV (spring 2016) • a diagnosis of a FGID is made • opposed to FGID only considered as a diagnosis of exclusion “When in Rome…” A. Esophageal Disorders C. Bowel Disorders A1. Heartburn C1. Irritable Bowel Syndrome A2. Chest Pain Presumed Esophageal C2. Functional Bloating A3. Functional Dysphagia C3. Functional Constipation A4. Globus C4. Functional Diarrhea C5. Unspecified Functional Bowel Disorder B. Gastroduodenal Disorders B1. DYSPEPSIA D. Abdominal Pain Syndrome B1a. Postprandial Distress Syndrome B1b. Epigastric Pain Syndrome E. Gallbladder and Sphincter of Oddi Disorders B2. BELCHING DISORDERS B2a. Aerophagia E1. Gallbladder Disorder B2b. Unspecified Excessive Belching E2. Biliary Sphincter of Oddi Disorder B3. NAUSEA/VOMITING DISORDERS E3. Pancreatic Sphincter of Oddi Disorder B3a. Chronic Idiopathic Nausea B3b. Functional Vomiting B3c. Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome B4. Rumination Syndrome in Adults “When in Rome…” F. Anorectal Disorders F1. Fecal Incontinence F2. ANORECTAL PAIN F2a. Chronic Proctalgia F2a.1. Levator Ani Syndrome F2a.2. Unspecified Functional Anorectal Pain F2b. Proctalgia Fugax F3. Defecation Disorders F3a. Dyssynergic Defecation F3b. Inadequate Defecatory Propulsion G. Childhood Functional GI Disorders: Infant/Toddler G1. Infant Regurgitation G2. Infant Rumination Syndrome G3. Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome G4. Infant Colic G5. Functional Diarrhea G6. Infant Dyschezia G7. Functional Constipation H. Childhood Functional GI Disorders: Child/Adolescent H1. VOMITING AND AEROPHAGIA H1a. Adolescent Rumination Syndrome H1b. Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome H1c. Aerophagia H2. ABDOMINAL PAIN-RELATED FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS H2a. Functional Dyspepsia H2b. Irritable Bowel Syndrome H2c. Abdominal Migraine H2d. Childhood Functional Abdominal Pain H2d1. Childhood Functional Abdominal Pain Syndrome H3. CONSTIPATION AND INCONTINENCE H3a. Functional Constipation H3b. Nonretentive Fecal Incontinence ABDOMINAL PAIN-RELATED FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS • • • • • Functional Dyspepsia Irritable Bowel Syndrome Abdominal Migraine Childhood Functional Abdominal Pain Childhood Functional Abdominal Pain Syndrome Functional Dyspepsia IBS Abdominal Migraine Functional Abdominal Pain FAP Syndrome • Bidirectional brain-gut interaction • Brain receives a stream of interoceptive input from the GI tract, integrates the information with other interoceptive information from the body and with contextual information from the environment, and sends an integrated response back to various target cells • Homeostasis of the GI tract during physiological perturbations and to adapt GI function to the overall state of the organism • Majority of information reaching the brain is not consciously perceived but serves primarily as input to autonomic reflex pathways • FAP syndromes, conscious perception of interoceptive information from the GI tract, or recall of interoceptive memories of such input, can occur in the form of constant or recurrent discomfort or pain Treatment of FGID • • • • Acknowledgement and Reassurance Medication Diet Therapies Simulation: • Parent: “Doctor, what is causing my child’s pain?” • Me: “I am not sure yet, but will try and help your child and you as we navigate through this process. It is possible we will be wrong before we find out what is causing it, and it may be that the symptom is the disease. Like a headache in the stomach.” PPIs • PPIs, however, have only a small benefit over placebo in the treatment of functional dyspepsia [Moayyedi et al. 2006] Histamine • Predominant dyspepsia, a short course of empiric therapy with an H2-histamine receptor antagonist is acceptable • Failure to respond or a recurrence of symptoms following discontinuation prompts further evaluation • Study showed only subjective improved in symptoms, and placebo was equally effective when looking at objective scores M.C. See, A.H. Birnbaum, C.B. Schecter, et al.: Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of famotidine in children with abdominal pain and dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 46:985-992 2001 Periactin • Cyproheptadine, a central and peripheral H1 nonselective histamine receptor antagonist with antiserotonergic properties • A double-blind, randomized, placebocontrolled trial was performed in 29 children ages 4 to 12 years with FAP – Randomized to placebo or cyproheptadine – 86% in the cyproheptadine group and 36% in the placebo group had improvement or resolution M. Sadeghian, F. Farahmand, G.H. Fallahi, et al.: Cyproheptadine for the treatment of functional abdominal pain in childhood: a double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial. Minerva Pediatr. 60:1367-1374 2008 Peppermint Oil • Soothe the GI tract for hundreds of years • Relaxes intestinal smooth muscle by decreasing calcium influx into the smooth muscle cells • Meta-analysis of five randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials performed in adult patients supported the efficacy of peppermint oil in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome • Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial in pediatric patients with IBS demonstrated the efficacy of entericcoated peppermint oil capsules in the reduction of pain during the acute phase of IBS R.M. Kline, J.J. Kline, J. Di Palma, et al.: Enteric-coated, pH-dependent peppermint oil capsules for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in children. J Pediatr. 138:125-128 2001 Anticholinergics • Dicyclomine (Bentyl) and hyoscyamine (Levsin) • Smooth muscle relaxants, block the muscarinic effects of acetylcholine on the GI tract, relaxing smooth muscle and reducing spasm and abdominal pain, slowing intestinal motility, and decreasing diarrhea • Efficacy not clearly established in adult trials, no randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in pediatrics • Potential side effects: drowsiness, blurred vision, dry mouth, tachycardia, constipation, and urinary retention • PRN or episodic, up to four times daily Tricyclic Antidepressants • Shown to provide relief to patients with FGIDs • Neuromodulatory and analgesic effects, from a combined anticholinergic effect on the gastrointestinal tract, mood elevation and central analgesia • Two clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of TCA therapy in the treatment of FAP in children – A single-center study of 33 adolescents with IBS found a beneficial effect of amitriptyline in comparison to placebo in terms of quality of life and pain relief – A multicenter randomized double-blinded trial on 90 children showed improvement in 59% of the children receiving amitriptyline* M. Saps, N. Youssef, A. Miranda, et al.: Multicenter, randomized, placebocontrolled trial of amitriptyline in children with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 137:1261-1269 2009 Serotonin • Serotonin is found in high concentrations in the enterochromaffin • 14 serotonin receptor subtypes with varying actions in the peripheral and central nervous systems exist • 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors appear to play a role in the pathophysiology of IBS SSRIs • Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are helpful for some patients with unremitting pain and impaired daily functioning, even if no depressive symptoms are present • Citalopram has been studied in children with FGIDs – 12-week open-label flexible-dose trial – By week 12, 50% rated their symptoms as very much improved – Also showed improvement in comorbid depression and anxiety J.V. Campo, J. Perel, A. Lucas, et al.: Citalopram treatment of pediatric recurrent abdominal pain and comorbid internalizing disorders: an exploratory study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 43:1234-1242 2004 5-HT3 antagonist • Ondansetron (Zofran) and Granisetron (Kytril) • Some chemotherapeutic and radiotherapeutic agents cause the release of 5-HT from enterochromaffin cells • Serotonin activates vagal afferents via 5-HT3 receptors, triggering emesis by stimulation of the area postrema and chemoreceptor trigger zone • Ondansetron and granisetron are very effective in reducing postchemotherapy nausea, but do not consistently alleviate the pain associated with FGIDs • Not routinely recommended for FGIDs unless nausea is a predominant symptom Probiotics • Double-blind randomized controlled trial, 50 children with IBS were treated with either Lactobacillus GG or placebo for 6 weeks – No significant differences between treatment and placebo groups with the exception of abdominal distention • Larger, 4-week placebo-controlled study, 104 patients who fulfilled the Rome II criteria for functional dyspepsia, IBS, or FAP – 25% in the treatment group and 9.6% in the placebo group responded to therapy – IBS more likely to respond to probiotic, compared to placebo or FAP M. Bausserman, S. Michail: The use of Lactobacillus GG in irritable bowel syndrome in children: a doubleblind randomized control trial. J Pediatr. 147:197-201 2005 A. Gawronska, Horbath A. Dziechciarz, et al.: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of Lactobacillus GG for abdominal pain disorders in children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 25:177-184 2007 • Microbiota + Carbohydrate (fuel) = Gas + Byproducts • Gas = Distension • Distension = Pain (nociceptor) • Byproducts = Absorption + Attraction H2O What Are Prebiotics? • Different kinds of fiber that encourage beneficial species of gut flora to grow • You can’t digest them, but your gut flora can – and more food for the gut flora means more flora! – PREbiotics provide food for the bacteria already living in your gut – PRObiotics provide a direct infusion of bacteria that weren’t there before – “Synbiotics” refers to supplements that combine probiotics and prebiotics Lactose, Fructose, FODMAPs…Oh my… • Breath tests • Elimination diets • Supplemental enzymes Prebiotic, Probiotic, Symbiotic … Oh my… • Prebiotics +/• Probiotics – which one, who do you trust • Symbiotic – does it even matter, and how would you even know What about evil gluten and Paleo? Cognitive Behavioral Therapy • 6 studies in a Cochrane review • Relatively small and had some weaknesses in design and reporting • Each reported a statistically significant benefit to participants in the intervention group • Cochrane reviewers thought CBT is worth considering A.A. Huertas-Ceballos, S. Logan, C. Bennett, C. Macarthur: Psychosocial interventions for recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in childhood (Review). Cochrane Library. (Issue 4)2009 Relaxation/Arousal Reduction • A variety of techniques to teach patients to counteract the physiological sequelae of stress or anxiety • The most commonly used techniques include progressive muscle relaxation training; biofeedback for striated muscle tension, skin temperature, or electrodermal activity; and transcendental or yoga meditation • Most techniques incorporate a quiet environment, a relaxed and comfortable body position, and a mental image to focus attention away from distracting thoughts or body perceptions • Audiotapes may be used to guide practice at home • Relaxation training has been shown in adults to significantly reduce gastrointestinal symptoms as compared with controls R.D. Anbar: Self-hypnosis for the treatment of functional abdominal pain in childhood. Clin Pediatr. 40:447-451 2001 www.CrosswordHobbyist.com/89649