PowerPoint 演示文稿

advertisement

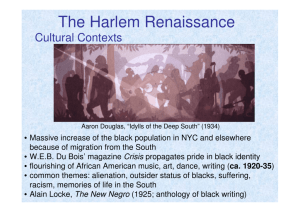

Chapter Fifteen: The Twentieth-Century Black Writer I. Social Background Black American literature has to be considered separately for the reason that it is all tied up with the bitter experience of the Black people. Because of the opprobrious (粗野的,无礼的) association the term “negro” had acquired through its southern use----more generally in the common derogatory variant “nigger” ---most Afro-Americans after emancipation much preferred the term “colored”. This was particularly true of the many freed men and women whose color ranged from dark brown to light tan (棕褐色的) or “high yellow”, indicating their mixed ancestry. In 1909 the first important national organization formed to gain respect for Afro-Americans as a group and improve their conditions named itself the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). However as time went on many of the more militant younger men and women felt that this terminology was an evasion, betraying a certain shame of one’s African ancestry, and should be replaced by the term Negro. After WWI the well-educated leaders of the Harlem Renaissance customarily wrote of “the New Negro”. Backward Forward Social Background The term was also honored in the name of an organization which boasted more than a million members in 1920. This was instituted by a Jamaican, Marcus Garvey, and called itself the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Today most socially aware Afro-Americans prefer the term “Blacks” which should therefore be used in any discussion of contemporary writers of issued. It would, however, be anachronistic(时代错误的) to insert it into material written before 1960. Until WWI more than three quarters of the black population were concentrated in the southern states. Except for a comparatively small number of house servants and a much smaller number of black professionals----doctors, ministers, teachers, undertakers---southern Negroes worked on the land, usually as sharecroppers with literally of functionally illiterate and most lived on the level of bare subsistence. Under the circumstances any black writer who hoped to live by his pen had, perforce (必然的), to address a white audience. This exposed him to pressure from at least two directions. Obviously he had to write what would prove acceptable to his potential white audience. Backward Forward Social Background And since he was writing fro outsiders, for readers who, kindly or unkindly, sympathetically or contemptuously, thought his people an inferior race, there was a tacit (默许)censorship imposed both by the black middle class and, often, his own conscience. This forbade him or her to provide ammunition for the enemy. Scenes of low life, frank treatment of “uncivilized” behavior, admissions of fundamental differences, were taboo. The tiny black bourgeoisie to be found in a very few cities, notably Philadelphia and New York, with some sons and daughters in Negro colleges, wished to believe, and make the world believe, that Negro society was just white society in black face. It even aped the color lines drawn by whites, valuing a light skin and “good hair, and discriminating against its own darker members. A street jingle ran, “If you are black, get back.” The revolt against the genteel tradition which shook late nineteenth century American literature did not and could not appear in Negro literature until after WWI. In addition to the immaterial barriers with which the black writer had to contend there were also, of course, enormous material difficulties. It was extremely difficult for a black writer to get even an occasional magazine story published and almost impossible to get even an occasional magazine have seen. Backward Forward Social Background Charles W. Chesnutt (1858-1932) did have four novels published but despite an enthusiastic recommendation by the leading critic of the period, William Dean Howells, Chesnutt’s novels met with little success and he wrote no more during the last twenty-seven years of his life. Dunbar, whose poetry we have noted, also wrote a number of short stories and four novels. Only one of the latter dealt with Negro life and none were either important or commercially successful. The most valuable and influential work of the early twentieth-century black writers was, in fact, not fiction. One of the most important themes in twentieth-century American history is the struggle of black Americans for their human and social rights. In 1863, during the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln had ended the slavery of blacks. But their position in American society remained very bad. In the South, especially government laws were used to keep black Americans in a low social position. There was also a powerful organization called the Ku Klux Klan which often used violence against blacks. Around the Turn of the Century, large numbers of blacks began moving from the South to the cities of the North. In such cities as New York, their situation was somewhat better. In the North, young black artists and writers began their long struggle for social justice for their people. Backward Forward Harlem Renaissance "From 1920 until about 1930 an unprecedented outburst of creative activity among African-Americans occurred in all fields of art. Beginning as a series of literary discussions in the lower Manhattan (Greenwich Village) and upper Manhattan (Harlem) sections of New York City, this African-American cultural movement became known as "The New Negro Movement" and later as the Harlem Renaissance. More than a literary movement and more than a social revolt against racism, the Harlem Renaissance exalted the unique culture of African-Americans and redefined African-American expression. African-Americans were encouraged to celebrate their heritage and to become "The New Negro," a term coined in 1925 by sociologist and critic Alain LeRoy Locke. One of the factors contributing to the rise of the Harlem Renaissance was the great migration of African-Americans to northern cities (such as New York City, Chicago, and Washington, D.C.) between 1919 and 1926. In his influential book The New Negro (1925), Locke described the northward migration of blacks as "something like a spiritual emancipation." Black urban migration, combined with trends in American society as a whole toward experimentation during the 1920s, and the rise of radical black intellectuals — including Locke, Marcus Garvey, founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), and W. E. B. Du Bois, editor of The Crisis magazine — all contributed to the particular styles and unprecedented success of black artists during the Harlem Renaissance period." Backward Forward W.E.B.Du Bois William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in Massachusetts in 1868, the year Congress guaranteed male black suffrage. Du Bois was graduated from Fisk University and Harvard University and studied two years at the University of Berlin. He was the first black American to receive the degree of doctor of philosophy from Harvard. Du Bois founded the Niagara Movement -- a group of African-American leaders committed to an active struggle for racial equality. Du Bois was a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and edited its journal, Crisis, for many years. A brilliant writer and speaker, Du Bois was the outstanding African-American intellectual of his time. His The Philadelphia Negro (1899) was the first sociological study of African-Americans. In The Souls of Black Folk (1903), Du Bois took a forceful stand against Booker T. Washington's policy of accommodation, calling instead for "ceaseless agitation and insistent demand for equality," and the "use of force of every sort: moral suasion, propaganda, and where possible even physical resistance." Backward Forward W.E.B.Du Bois Excerpts: On the Color-line Herein lie buried many things which if read with patience may show the strange meaning of being black here in the dawning of the Twentieth Century. This meaning is not without interest to you, Gentle Reader; for the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line. The Forethought I have seen a land right merry with the sun, where children sing, and rolling hills lie like passioned women wanton with harvest. And there in the King's Highway sat and sits a figure veiled and bowed, by which the traveller's footsteps hasten as they go. On the tainted air broods fear. Three centuries' thought has been the raising and unveiling of that bowed human heart, and now behold a century new for the duty and the deed. The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line. Backward Forward Jean Toomer (1894-1967) Jean Toomer was born in 1894 in Washington, D.C, the son of a Georgian farmer. Though he passed for white during certain periods of his life, he was raised in a predominantly black community and attended black high schools. In 1914, he began college at the University of Wisconsin but transferred to the College of the City of New York and studied there until 1917. Toomer spent the next four years writing and published poetry and prose in Broom, The Liberator, The Little Review and others. He actively participated in literary society and was acquainted with such prominent figures as the critic Kenneth Burke, the photographer Alfred Steiglitz and the poet Hart Crane. In 1921, Toomer took a teaching job in Georgia and remained there four months; the trip represented his journey back to his Southern roots. His experience inspired his book Cane, a book of prose poetry describing the Georgian people and landscape. In the early twenties, Toomer became interested in Unitism, a religion founded by the Armenian George Ivanovich Gurdjieff. The doctrine taught unity, transcendence and mastery of self through yoga: all of which appealed to Toomer, a light-skinned black man preoccupied with establishing an identity in a society of rigid race distinctions. Backward Forward Jean Toomer (1894-1967) He began to preach the teachings of Gurdjieff in Harlem and later moved downtown into the white community. From there, he moved to Chicago to create a new branch of followers. Toomer was married twice to wives who were white, and was criticized by the black community for leaving Harlem and rejecting his roots for a life in the white world; however, he saw himself as an individual living above the boundaries of race. His meditations center around his longing for racial unity, as illustrated by his long poem "Blue Meridian." He died in 1967. A Selected Bibliography Poetry Cane (1923) The Collected Poems of Jean Toomer (1980) Prose Essentials (1931) The Wayward and the Seeking: A Collection of Writings by Jean Toomer (1980) Backward Forward Song of the Son Pour O pour that parting soul in song, O pour it in the sawdust glow of night, Into the velvet pine-smoke air to-night, And let the valley carry it along. And let the valley carry it along. O land and soil, red soil and sweet-gum tree, So scant of grass, so profligate of pines, Now just before an epoch's sun declines Thy son, in time, I have returned to thee, Thy son, I have in time returned to thee. In time, for though the sun is setting on A song-lit race of slaves, it has not set; Though late, O soil, it is not too late yet To catch thy plaintive soul, leaving, soon gone, Leaving, to catch thy plaintive soul soon gone. Backward Forward Song of the Son O Negro slaves, dark purple ripened plums, Squeezed, and bursting in the pine-wood air, Passing before they stripped the old tree bare One plum was saved for me, one seed becomes An everlasting song, a singing tree, Caroling softly souls of slavery, What they were, and what they are to me, Caroling softly souls of slavery. Backward Forward Reapers Black reapers with the sound of steel on stones Are sharpening scythes. I see them place the hones In their hip-pockets as a thing that's done, And start their silent swinging, one by one. Black horses drive a mower through the weeds, And there, a field rat, startled, squealing bleeds. His belly close to ground. I see the blade. Blood-stained, continue cutting weeds and shade. From Cane by Jean Toomer. Copyright © 1923 Boni and Liveright, renewed 1951 by Jean Toomer. Used with the permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation. Backward Forward Introduction to Cane LOOKING back on the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920's, the distinguished scholar and sociologist, Charles S. Johnson, observed that "A brief ten years have developed more confident self-expression, more widespread efforts in the direction of art than the long, dreary two centuries before." Recalling the sunburst of Jean Toomer's first appearance, he added, "Here was triumphantly the Negro artist, detached from propaganda, sensitive only to beauty. Where [Paul Laurence] Dunbar gave to the unnamed Negro peasant a reassuring touch of humanity, Toomer gave to the peasant a passionate charm.... More than artist, he was an experimentalist, and this last quality has carried him away from what was, perhaps, the most astonishingly brilliant beginning of any Negro writer of this generation."Cane, the book that provoked this comment, was published in 1923 after portions of it had appeared earlier in Broom, The Crisis, Double Dealer, Liberator, Little Review, Modern Review, Nomad, Prairie and S 4 N. But Cane and its author, let it be said at once, presented an enigma from the start-an enigma which has, in many ways, deepened in the years since its publication. Given such a problem, perhaps one may be excused for not wishing to separate completely the man from his work. During the summer of 1922 Toomer had sent a batch of unpublished manuscripts to the editors of the Liberator, Max Eastman and his assistant Claude McKay. They accepted some of the pieces enthusiastically and requested biographical material from the author. Toomer responded with the following: Backward Forward Langston Hughes James Langston Hughes was born February 1, 1902, in Joplin, Missouri. His parents divorced when he was a small child, and his father moved to Mexico. He was raised by his grandmother until he was thirteen, when he moved to Lincoln, Illinois, to live with his mother and her husband, eventually settling in Cleveland, Ohio. It was in Lincoln, Illinois, that Hughes began writing poetry. Following graduation, he spent a year in Mexico and a year at Columbia University. During these years, he held odd jobs as an assistant cook, launderer, and a busboy, and traveled to Africa and Europe working as a seaman. In November 1924, he moved to Washington, D.C. Hughes first book of poetry, The Weary Blues, was published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1926. He finished his college education at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania three years later. In 1930 his first novel, Not without Laughter, won the Harmon gold medal for literature. Hughes, who claimed Paul Lawrence Dunbar, Carl Sandburg, and Walt Whitman as his primary influences, is particularly known for his insightful, colorful portrayals of black life in America from the twenties through the sixties. Backward Forward Langston Hughes He wrote novels, short stories and plays, as well as poetry, and is also known for his engagement with the world of jazz and the influence it had on his writing, as in Montage of a Dream Deferred. His life and work were enormously important in shaping the artistic contributions of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. Unlike other notable black poets of the period—Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, and Countee Cullen--Hughes refused to differentiate between his personal experience and the common experience of black America. He wanted to tell the stories of his people in ways that reflected their actual culture, including both their suffering and their love of music, laughter, and language itself. Langston Hughes died of complications from prostate前列腺 cancer in May 22, 1967, in New York. In his memory, his residence at 20 East 127th Street in Harlem, New York City, has been given landmark status by the New York City Preservation Commission, and East 127th Street was renamed "Langston Hughes Place." Backward Forward I, Too, Sing America I, too, sing America. I am the darker brother. They send me to eat in the kitchen When company comes, But I laugh, And eat well, And grow strong. Tomorrow, I'll be at the table When company comes. Nobody'll dare Say to me, "Eat in the kitchen," Then. Besides, They'll see how beautiful I am And be ashamed-I, too, am America. Backward Forward The Negro Speaks of Rivers I've known rivers: I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins. My soul has grown deep like the rivers. I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young. I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep. I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it. I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I've seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset. I've known rivers: Ancient, dusky rivers. My soul has grown deep like the rivers. Backward Forward Countee Cullen (1903-1946) Born in 1903 in New York City, Countee Cullen was raised in a Methodist parsonage. He attended De Witt Clinton High School in New York and began writing poetry at the age of fourteen. In 1922, Cullen entered New York University. His poems were published in The Crisis, under the leadership of W. E. B. Du Bois, and Opportunity, a magazine of the National Urban League. He was soon after published in Harper's, the Century Magazine, and Poetry. He won several awards for his poem, "Ballad of the Brown Girl," and graduated from New York University in 1923. That same year, Harper published his first volume of verse, Color, and he was admitted to Harvard University where he completed a master's degree. His second volume of poetry, Copper Sun (1927), met with controversy in the black community because Cullen did not give the subject of race the same attention he had given it in Color. He was raised and educated in a primarily white community, and he differed from other poets of the Harlem Renaissance like Langston Hughes in that he lacked the background to comment from personal experience on the lives of other blacks or use popular black themes in his writing. An imaginative lyric poet, he wrote in the tradition of Keats and Shelley and was resistant to the new poetic techniques of the Modernists. He died in 1946. Backward Forward A Selected Bibliography Poetry Color (1925) Copper Sun (1927) The Ballad of the Brown Girl (1928) The Black Christ and Other Poems (1929) The Medea and Some Other Poems (1935) On These I Stand: An Anthology of the Best Poems of Countee Cullen (1947) My Soul's High Song: The Collected Writings of Countee Cullen (1991) Prose One Way to Heaven (1931) The Lost Zoo (1940) Children's stories. My Lives and How I Lost Them (1942) Children's stories. Drama St. Louis Woman (1946) With Arna Bontemps. Backward Forward "Yet Do I Marvel" I doubt not God is good, well-meaning, kind, And did He stoop to quibble could tell why The little buried mole continues blind, Why flesh that mirrors Him must some day die, Make plain the reason tortured Tantalus Is baited by the fickle fruit, declare If merely brute caprice dooms Sisyphus To struggle up a never-ending stair. Inscrutable His ways are, and immune To catechism by a mind too strewn With petty cares to slightly understand What awful brain compels His awful hand. Yet do I marvel at this curious thing: To make a poet black, and bid him sing! (Concise Anthology of American Literature, p1702) Backward Forward Richard Wright (1908-1960) The day Native Son appeared, American culture was changed forever. No matter how much qualifying the book might later need, it made impossible a repetition of old lies." - Irving Howe One of America’s greatest black writers, Richard Wright was also among the first African American writers to achieve literary fame and fortune, but his reputation has less to do with the color of his skin than with the superb quality of his work. He was born and spent the first years of his life on a plantation, not far from the affluent city of Natchez on the Mississippi River, but his life as the son of an illiterate sharecropper was far from affluent. Though he spent only a few years of his life in Mississippi, those years would play a key role in his two most important works: Native Son, a novel, and his autobiography, Black Boy. Richard Wright was born on a plantation near Natchez, Mississippi, on September 4, 1908. His father, Nathaniel, was an illiterate sharecropper and his mother, Ella Wilson, was a well-educated school teacher. The family’s extreme poverty forced them to move to Memphis when Richard was six years old. Backward Forward Richard Wright (1908-1960) Soon after, his father left the family for another woman and his mother was forced to work as a cook in order to support the family. Richard briefly stayed in an orphanage during this period as well. His mother became ill while living in Memphis, so the family moved to Jackson, Mississippi, and lived with Ella’s mother. Richard’s grandmother, a devout Seventh Day Adventist, enrolled him in a Seventh Day Adventist school near Jackson at the age of twelve. He also attended a local public school for a few years. In the spring of 1924 the Southern Register, a local black newspaper, printed his first story, “The Voodoo of Hell’s Half Acre.” From 1925 to 1927, he worked several menial 仆人的jobs in Jackson and Memphis. During this time he continued writing and discovered the works of H.L. Mencken, Theodore Dreiser, and Sinclair Lewis. In 1927 he moved to Chicago, where he became a Post Office clerk until the Great Depression forced him to take on various temporary positions. During this time he became involved with the Communist Party, writing articles and stories for both the Daily Worker and New Masses. In April 1931 he published his first major story, “Superstition,” in Abbot’s Monthly. His ties to the Communist Party continued after moving to New York in 1937. Backward Forward Richard Wright (1908-1960) He became the Harlem editor of the Daily Worker and helped edit a short-lived literary magazine, New Challenge. In 1938 four of his stories were collected as Uncle Tom’s Children. He then received a Guggenheim古根海姆Fellowship, which allowed him to complete his first novel, Native Son (1940). In 1939, he married Dhimah Rose Meadman, a white dancer, but the two separated shortly thereafter. In 1941, he married Ellen Poplar, a white member of the Communist Party, and they had two daughters, Julia in 1942 and Rachel in 1949. In 1944 he broke with the Communist Party but continued to follow liberal ideologies. After moving to Paris in 1946, Wright became friends with Jean-Paul Sartre萨特 and Albert Camus加谬 while going through an Existentialist phase best depicted by his second novel, The Outsiders 局外人(1953). In 1954 he published a minor novel, Savage Holiday. After becoming a French citizen in 1947, he continued to travel throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa, and these experiences led to a number of nonfiction works. In his last years, he was plagued by illness (aerobic dysentary) and financial hardship. Throughout this period he wrote approximately 4,000 English Haikus俳句 (some of which were recently published for the first time) and another novel, The Long Dream, in 1958. He also prepared another collection of short stories, Eight Men, which was published after his death on November 28, 1960. Backward Forward Richard Wright (1908-1960) Among his other works are two autobiographies. Black Boy, published in 1945, covered his youth in the segregated South, and American Hunger, published posthumously in 1977, treated his membership and disillusionment with the Communist Party. Many of Wright’s works failed to satisfy the rigid standards of the New Criticism, but his evolution as a writer has interested readers throughout the world. The importance of his works comes not from his technique and style, but from the impact his ideas and attitudes have had on American life. Wright is seen as a seminal figure in the black revolution that followed his earliest novels. Bigger Thomas, the central figure of Native Son, is a murderer, but his situation galvanized 刺激, 使兴奋, 激励the thought of black leaders toward the desire to confront the world and help shape the future of their race. As his vision of the world extended beyond the U.S., his quest for solutions expanded to include the politics and economics of emerging third world nations. Wright’s development was marked by an ability to respond to the currents of the social and intellectual history of his time. His most significant contribution, however, was his desire to accurately portray blacks to white readers, thereby destroying the white myth of the patient, humorous, subservient屈从的 black man. Backward Forward Fiction Uncle Tom’s Children: Four Novellas. New York: Harper, 1938. Uncle Tom’s Children: Five Long Stories. New York: Harper, 1938. Bright and Morning Star (story). New York: International Publishers, 1938. Native Son. New York: Harper, 1940. The Outsider. New York: Harper, 1953. Savage Holiday. New York: Avon, 1954. The Long Dream. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1958. Eight Men (stories). Cleveland and New York: World, 1961. Lawd Today. New York: Walker, 1963. Backward Forward Native Son Richard Wright’s Native Son is an essential text of AfricanAmerican literature and a great piece of reading. The novel is the tragic story of Bigger Thomas, a hard-working, honest black man trying to get by in the white man’s world. When he takes a job as a chauffeur for a wealthy white family with a left-leaning college-age daughter, he sees trouble inexplicably coming his way. How it happens will leave you spellbound出神的, and will also show how a person with the best intentions can be trapped in a noose 束缚of race and class. Native Son's publication history is one of its most revelatory启示的 aspects. After several novel-projects had failed, Wright sold Native Son to Harper Publishers, netting a $400 advance预付. Published in 1940, Native Son became a selection of the Book-ofthe-Month club. Ironically, some of the most candid commentary on racism and communism was censored from the novel in its publication for the Book-of-the-Month club. Perhaps more ironic is the fact that the novel was featured as a detective story; Wright's discussions about race and poverty were largely considered to be incidental at best, if not distracting, or worse. It was not until 1991 that Native Son was printed in its original form and literary critics and professors alike agreed that the substantial additions to the novel significantly enhanced its political and literary weight. Backward Forward Native Son Some of the most notable additions can be found in the courtroom scenes of Book Three. While the outcome of the trial is no different, much of Boris A. Max's Communist philosophy was restored. Similarly, there is more graphic detail of the violence of the racist white mob, now including an enhanced portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan三K党. Finally, the restored details of Bigger's psychology support the idea that the inmate's final contemplation is spiritually transforming. The censorship of Native Son speaks to the political context displayed in the novel. The array of racist, anti-Communists like Britten, the private investigator, and Buckley, the state prosecutor, reminds one of the political problems that Wright suffered in the "red scares" of McCarthy-era America. Similarly, the story of Bigger's family‹their migration and poverty provides the context of the Great Depression; but more specifically, Native Son focuses on the experiences of African-Americans and how economic disadvantages are so closely related to and entwined缠绕 with political subjugation征服. In the novel, Wright essentially reports his findings, that racist Chicago is little better than the South and northern blacks are just as impoverished as their southern counterparts. Backward Forward Ralph Ellison Ralph Ellison’s life began on March 1, 1914 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Ellison was forced to face hardships as a young child. He first lost a brother when he was very young. Then in 1917, at the age of three, Ellison’s father died and his mother was left to raise two young sons. As a child he was influenced by the western frontier philosophy of America. He viewed our American nation as a land of “infinite possibilities.” He did not have to face many racial tensions growing up in the Midwest, this caused for a culture shock when he witnessed the harshness of the deep south for the first time. This occurred when he went to school on a scholarship at the Tuskegee Institute from 1933 to 1936. While at Tuskegee his main interest was found in music and this was what his career plans were. In the year of 1936 Ellison left the Tuskegee Institute for the city, New York City. While in the city he met the novelist Richard Wright and became involved in the Federal Writers Project. During these times he published many short stories for magazines. His stories appeared in New Masses and other random periodicals. Next Ellison became the editor of the Negro Quarterly and soon after began work of his first novel. During his stay in New York he also took a time off to serve in the Merchant Marine academy in the second World War. Following is a list of the most famous works, and dates they wore published, created by this wonderful author during his lifetime. Backward Forward Background Information Ellison gained valuable writing experience while working for the Federal Writers' Project between 1938 and 1942. Through his work, he came into close contact with a variety of people and thus became better adept at producing realistic characters in his writing. Many of the conversations he recorded he then used when he was writing The Invisible Man. For instance, Mary Rambo's character advises the narrator of the novel to not let New York corrupt him. This quotation is verbatim逐字的 out of his FWP encounters. Another experience which was later encapsulated压缩 into his novel was his work in freelance writing. In 1943, he was hired to cover a riot in Harlem. This event provided the background for the climax of the novel, the race riot, which finally succeeds in driving the narrator underground in The Invisible Man. While in the Merchant Marines during World War II, Ellison struggled with writing a prison camp novel. He contracted a kidney infection and became depressed. He took a sick leave as the War wound down in 1945 and moved with his wife to recuperate复原 in Vermont. He spent time reading Lord Raglan's The Hero which discusses AfricanAmerican mythical and historical figures. Also influenced by the likes of Sophocles, Homer, Dostoyevsky, Freud, Jung, Wright, and others, he began to think about black leaders and wondered why they ignored their constituents but often bent over backwards for the white man. Backward Forward He decided to write a novel about black identity, heroism, and history through the use of the folklore, spirituals, blues, comedians, archetypes, and personal experiences he had gathered over the years. One day in 1945, Ellison sat at his typewriter in Vermont, thinking of an ironic joke he had heard from a black face comedian about his family becoming so progressively dark in complexion that the new baby's mother could not even see her. In this vein, he suddenly wrote, "I am an invisible man". He nearly rejected the idea but was intrigued and decided to give it a try. Ellison then spent seven years working on the novel, The Invisible Man. In October of 1947, Ellison published the battle royal chapter as "Invisible Man" in the British magazine, Horizon. In 1948, he published the same section in the American magazine, Magazine of the Year. Subsequently, in the early months of 1952, he published the Prologue of the novel in the Partisan Review. The complete novel was then published in April of 1952. It received favorable reviews by both white and black audiences, although it was also met with some negative reviews. Harsh criticism came from a minority of the Afro-American community who claimed that the novel displayed contempt toward blacks. The Left also was a harsh critic, finding the novel to be pretentious and otherworldly. Overall however, the book was greeted positively. Over the years it has been awarded with numerous accolades赞美, such as the Russwurm Award, National Book Award, Rockefeller Foundation Award, and Prix de Rome Fellowships from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Backward Forward James Baldwin James Arthur Baldwin was born in Harlem, New York City, Aug. 2, 1924 and died on Nov. 30, 1987. He offered a vital literary voice during the era of civil rights activism in the 1950s and '60s. The eldest of nine children, his stepfather was a minister. At age 14, Baldwin became a preacher at the small Fireside Pentecostal Church in Harlem. After he graduated from high school, he moved to Greenwich Village. In the early 1940s, he transferred his faith from religion to literature. Critics, however, note the impassioned cadences调子 of Black churches are still evident in his writing. Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), his first novel, is a partially autobiographical account of his youth. His essay collections [Notes of a Native Son (1955), Nobody Knows My Name (1961), and The Fire Next Time (1963)] were influential in informing a large white audience. From 1948, Baldwin made his home primarily in the south of France, but often returned to the USA to lecture or teach. In 1957, he began spending half of each year in New York City. His novels include Giovanni's Room (1956), about a white American expatriate who must come to terms with his homosexuality, and Another Country (1962), about racial and gay sexual tensions among New York intellectuals. His inclusion of gay themes resulted in a lot of savage criticism from the Black community. Backward Forward James Baldwin Eldridge Cleaver, of the Black Panthers黑豹, stated the Baldwin's writing displayed an "agonizing, total hatred of blacks." Baldwin's play, Blues for Mister Charlie, was produced in 1964. Going to Meet the Man (1965) and Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone (1968) provided powerful descriptions of American racism. As an openly gay man, he became increasingly outspoken in condemning discrimination against lesbian and gay people. Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953) The Amen Corner (play, 1965) Works by James Baldwin Notes of a Native Son (1955) Giovanni's Room (1956) Nobody Knows My Name (1961) Another Country (1962) The Fire Next Time (1963) Blues for Mister Charlie (play, 1964) Going to Meet the Man (1965) Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone (1968) No Name in the Street (1972) Backward Forward Go Tell It on the Mountain In Go Tell It on the Mountain, author James Baldwin describes the course of the fourteenth birthday of John Grimes in Harlem, 1935. Baldwin also uses extended flashback episodes to recount the lives of John's parents and aunt and to link this urban boy in the North to his slave grandmother in an earlier South. The first section follows John's thoughts, the second mostly his aunt’s, the third his father’s, the fourth his mother’s and the fifth again mostly John's. The title Go Tell It on the Mountain comes from a Negro spiritual. The novel is steeped in the language of the King James Bible, and the Bible is a constant presence in the characters' lives; thus, a familiarity with Biblical stories can enhance the reader's understanding of the text. At the heart of the story three main conflicts intertwine: a clash between father and son, a coming-of-age struggle, and a religious crisis. Baldwin deals with issues of race and racism more elliptically in this novel than in his other works, but these issues inform all three of the text's central problems--indeed, according to some critics, these issues take center stage in the book, though subtly. Backward Forward Go Tell It on the Mountain John doesn't understand why his father hates him, reserving his love for John's younger brother Roy instead. He is torn between his desire to win his father's love and his hatred for his father (and the strict religious world this man represents). The boy believes himself to have committed the first major sin of his life--a belief that helps precipitate a religious crisis. Before the night is over John will undergo a religious transformation, experiencing salvation on the "threshing-floor" of his family's storefront Harlem church. Yet this will not earn him his father's love. What John does not know, but the reader does, is that the man he thinks is his father--Gabriel--is, in fact, his stepfather; unbeknownst to John, Gabriel's resentment of him has nothing to do with himself and everything to do with Gabriel's own concealed past. Backward Forward Another Country Synopsis: Opening with the unforgettable character of Rufus Scott, a scavenging Harlem jazz musician adrift in New York, it draws us into a Bohemian underworld of writers and artists as they betray, love and test each other - men and women, men and men, black and white - to the limit. First lines: He was facing Seventh Avenue, at Times Square. It was past midnight and he had been sitting in the movies, in the top row of the balcony, since two o'clock in the afternoon. Twice he had been awakened by the violent accents of the Italian film, once the usher had awakened him, and twice he had been awakened by caterpillar fingers between his thighs. He was so tired, he had fallen so low, that he scarcely had the energy to be angry; nothing of his belonged to him anymore - you took the best, so why not take the rest? - but he had growled in his sleep and bared the white teeth in his dark face and crossed his legs. Then the balcony was nearly empty, the Italian film was approaching a climax; he stumbled down the endless stairs into the street. He was hungry, his mouth felt filthy. He realised too late, as he passed through the doors, that he wanted to urinate. And he was broke. And he had nowhere to go. Backward Forward Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones) Amiri Baraka was born Everett LeRoi Jones in Newark, New Jersey, on October 7, 1934. His father, Colt LeRoy Jones, was a postal supervisor; Anna Lois Jones, his mother, was a social worker. He attended Rutgers University for two years, then transferred to Howard University, where in 1954 he earned his B.A. in English. He served in the Air Force from 1954 until 1957, then moved to the Lower East Side of Manhattan. There he joined a loose circle of Greenwich Village artists, musicians, and writers. The following year he married Hettie Cohen and began co-editing the avant-garde literary magazine Yugen with her. That year he also founded Totem Press, which first published works by Allen Ginsbere, Jack Kerouac, and others. He published his first volume of poetry, Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note, in 1961. From 1961 to 1963 he was co-editor, with Diane Di Prima, of The Floating Bear, a literary newsletter. His increasing hostility toward and mistrust of white society was reflected in two plays, The Slave and The Toilet, both written in 1962. 1963 saw the publication of Blues People: Negro Music in White America, which he wrote, and The Moderns: An Anthology of New Writing in America, which he edited and introduced. His reputation as a playwright was established with the production of Dutchman at the Cherry Lane Theatre in New York on March 24, 1964. Backward Forward Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones) The controversial play subsequently won an Obie Award (for "best off-Broadway play") and was made into a film. In 1965, following the assassination of Malcolm X, Jones repudiated批判 his former life and ended his marriage. He moved to Harlem, where he founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School由固定剧团演出保留剧目的剧场. The company, which produced plays that were often anti-white and intended for a black audience, dissolved 解散 in a few months. He moved back to Newark, and in 1967 he married AfricanAmerican poet Sylvia Robinson (now known as Amina Baraka). That year he also founded the Spirit House Players, which produced, among other works, two of Baraka's plays against police brutality: Police and Arm Yrself or Harm Yrself. In 1968, he co-edited Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing with Larry Neal and his play Home on the Range was performed as a benefit for the Black Panther party. That same year he became a Muslim, changing his name to Imamu Amiri Baraka. ("Imamu" means "spiritual leader.") He assumed leadership of his own black Muslim organization, Kawaida. From 1968 to 1975, Baraka was chairman of the Committee for Unified Newark, a black united front organization. In 1969 , his Great Goodness of Life became part of the successful "Black Quartet" off-Broadway, and his play Slave Ship was widely reviewed. Backward Forward Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones) Baraka was a founder and chairman of the Congress of African People, a national PanAfricanist organization with chapters in 15 cities, and he was one of the chief organizers of the National Black Political Convention, which convened in Gary, Indiana, in 1972 to organize a more unified political stance for African-Americans. In 1974 Baraka adopted a Marxist Leninist philosophy and dropped the spiritual title "Imamu." In 1983, he and Amina Baraka edited Confirmation: An Anthology of AfricanAmerican Women, which won an American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation, and in 1987 they published The Music: Reflections on Jazz and Blues. The Autobiography of LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka was published in 1984. Amiri Baraka's numerous literary prizes and honors include fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, the PEN/Faulkner Award, the Rockefeller Foundation Award for Drama, the Langston Hughes Award from The City College of New York, and a lifetime achievement award from the Before Columbus Foundation. He has taught poetry at the New School for Social Research in New York, literature at the University of Buffalo, and drama at Columbia University. He has also taught at San Francisco State University, Yale University and George Washington University. Backward Forward A Selected Bibliography Poetry Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note (1961) The Dead Lecturer (1964) Black Art (1969) Black Magic: Collected Poetry 1961-1967 (1969) It's Nation Time (1970) Spirit Reach (1972) Selected Poetry of Amiri Baraka/LeRoi Jones (1979) The Leroi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader (1991) ed. William J. Harris Wise Why's Y's: The Griot's Tale (1995) Transbluesency: The Selected Poetry of Amiri Baraka/Leroi Jones (1961-1995) Funk Lore: New Poems (1984-1995) (1996) Backward Forward Alex Haley (1921-1992) The author of the widely acclaimed novel Roots was born in Ithaca, New York on August 11, 1921, and reared in Henning, Tennessee. The oldest of three sons of a college professor father and a mother who taught grade school, Haley graduated from high school at fifteen and attended college for two years before enlisting in the United States Coast Guard as a messboy in 1939. A voracious贪婪的 reader, Haley began writing short stories while working at sea, but it took eight years before small magazines began accepting some of his stories. By 1952, the Coast Guard had created a new rating for Haley, chief journalist, and he began handling United States Coast Guard public relations. In 1959, after 20 years of military service, he retired from the Coast Guard and launched a new career as a freelance writer. He eventually became an assignment writer for Reader's Digest and moved on to Playboy where he initiated the "Playboy Interviews" feature. Backward Forward The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) One of the personalities Haley interviewed was Malcolm X-- an interview that inspired Haley's first book, The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965). Translated into eight languages, the book has sold more than 6 million copies. Pursuing the few slender clues of oral family history told him by his maternal grandmother in Tennessee, Haley spent the next 12 years traveling three continents tracking his maternal family back to a Mandingo youth, named Kunta Kinte, who was kidnaped into slavery from the small village of Juffure, in The Gambia, West Africa. "Through a life of passion and struggle, he became one of the most influential figures of the 20th Century. In this riveting account, he tells of his journey from a prison cell to Mecca, describing his transition from hoodlum to Muslim minister. Here, the man who called himself "the angriest Black man in America" relates how his conversion to true Islam helped him confront his rage and recognize the brotherhood of all mankind. An established classic of modern America, The Autobiography of Malcolm X was hailed by the New York Times as "Extraordinary. A brilliant, painful, important book." Still extraordinary, still important, this electrifying story has transformed Malcom X's life into his legacy. The strength of his words, the power of his ideas continue to resonate more than a generation after they first appeared." Backward Forward Roots It begins with a child's birth in Africa. His parents name him Kunta Kinte, a strong, proud boy who later in life is kidnapped and taken to America to be sold into slavery. Roots follows his clan through seven generations, ending with Alex Haley himself. The book tells, in fascinating detail, the lives of Kunta Kinte, Kizzy Waller, "Chicken George" Lea, Tom Murray, Will Palmer, Simon Alexander Haley, and finally, the author. Throughout the book, African culture, as well as the culture of Americanized slaves, is introduced. Haley's book stimulated interest in Africa and in black genealogy家谱. The United States Senate passed a resolution paying tribute to Haley and comparing Roots to Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe in the 1850s. The book received many awards, including the National Book Award for 1976 special citation of merit in history and a special Pulitzer Prize in 1976 for making an important contribution to the literature of slavery. Roots was not without its critics, however. A 1977 lawsuit brought by Margaret Walker charged that Roots plagiarized her novel Jubilee. Another author, Harold Courlander also filed a suit charging that Roots plagiarized his novel The African. Courlander received a settlement after several passages in Roots were found to be almost verbatim逐字的 from The African. Haley claimed that researchers helping him had given him this material without citing the source. Backward Forward Roots Haley received the NAACP's Spingarn Medal in 1977. Four thousand deans and department heads of colleges and universities throughout the country in a survey conducted by Scholastic Magazine selected Haley as America's foremost achiever in the literature category. (Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.was selected in the religious category.) The ABC-TV network presented another series, Roots: The Next Generation, in February 1979 (also written by Haley). Roots had sold almost five million copies by December 1978 and had been reprinted in 23 languages. In 1988, Haley conducted a promotional tour for a novella titled A Different Kind of Christmas about slave escapes in the 1850s. He also promoted a drama, Roots: The Gift, a two-hour television program shown in December 1988. This story revolved around two principal characters from Roots who are involved in a slave break for freedom on Christmas Eve. When Roots appeared in 1976 it gained critical and popular success, although the truth and originality of the book faced criticism. James Baldwin considered in his New York Times review, that Roots suggest how each of us are vehicle of the history which have produced us. On the other side - representing a minority opinion - Michael Arled viewed the book and television series as Haley's own fantasies about 'going home.'The story starts from Juffure, a small peaceful village in West Africa in 1750. It ends in Gambia, in the same village, after several generations. Backward Forward Roots Haley depicts realistically his ancestor's life - the villagers suffered occasionally from shortage of food. "But Kunta and the others, being yet little children, paid less attention to the hunger pangs in their bellies than to playing in the mud, wrestling each other and sliding on their naked bottoms. Yet in their longing to see the sun again, they would wave up at the slate-colored sky and shout - as they had seen their parents do - 'Shine, sun, and I will kill you a goat!'" Haley doesn't imagine that it is possible to return to some Paradise. In Juffure, among the villages, he realizes in shock that the color of his skin is much lighter than theirs. Skeptics claimed that the griot, Kebba Kanji Fofana, an old man, was a well-known trickster and told Haley just what he wanted to hear. However, Haley donated money to the village for a new mosque. He had also founded in the early 1970s with his brothers the Kinte Foundation to collection and preservation of African-American genealogy records. Selected Books by Alex Haley Backward Roots •The Autobiography of Malcolm X by Malcolm X •Marva Collins' Way •Alex Haley's Queen: The Story of an American Family •Climbing Your Family Tree: Online and Off-line Genealogy for Kids •A Different Kind of Christmas Forward