Bishop Guertin-Demers-Iuliano-Aff-New Trier

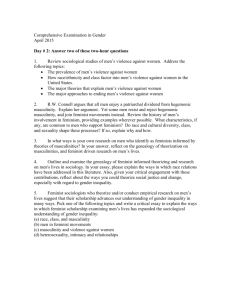

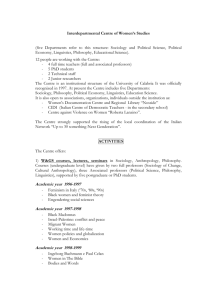

advertisement