Master of ARTS - Jack H. David Jr.

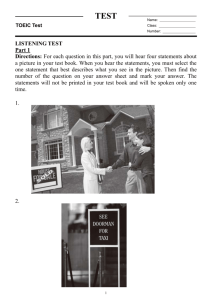

advertisement