CANAR Presentation Tribal Gangs and Evidence

advertisement

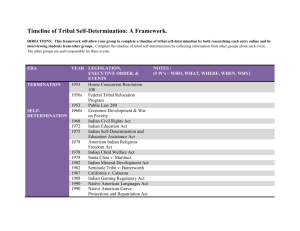

Gordon Swensen, M.S., LVRC, CRC, CPM, GCDF Director of Statewide Strategic Alliances and Initiatives Utah State Office of Rehabilitation Division of Rehabilitation Services gswensen@utah.gov CANAR Annual Conference Salt Lake City, Utah November 12, 2015 So How Motivated Are You? You’ve seen the motivational posters on everything from Courage, Faith, Persistence, Patience, Leadership, Integrity, Love, Endurance, Loyalty, Service, Friendship, Courtesy, Kindness…and all the rest! Let’s Take a Look! It’s the Last Day of the Conference and Getting to the Airport, and Hopefully Not Being Delayed, and Finally Arriving Home Exhausted…so maybe a few “NonMotivational” messages may be exactly what you need right now! DELINQUENCY, DISABILITY, and THE VR Process “We sometimes are called upon to work with people for whom all others have abandoned hope. Perhaps we have even come to the conclusion that there’s no possibility of change or growth. It’s at that time that, if we can find the tiniest scrap of hope, we may turn the corner, achieve a measurable gain, save someone worth saving…” (Hanoch McCarty) Native American Youth Gangs Learning Objectives: Indian Country Research on Youth Gangs Tools and Resources (Tricks of the Trade) for Service Providers Offender Re-Entry Issues Following Incarceration Collaboration and Partnerships that Work A Change in Perspective Delinquency, Disability, and The VR Process “Billions of dollars have been channeled into rehabilitation programs with few positive results. Yet the concepts of ‘rehabilitation’ as applied to the criminal personality is a misconception and a misnomer. To ‘rehabilitate’ means to restore to an earlier constructive state or condition. Offender rehabilitative measures have included providing educational opportunities, job skills, social skills, counseling and therapy. This resulted in criminals who have education, job skills, social skills, and occasional personal insights. They remained, however, criminals. “The rehabilitative measures were well-conceived and somewhat useful, but they did not touch the core of the criminal-the way he thinks…What is necessary is to know who the criminal is and how he thinks. Then it becomes possible to approach him more realistically in terms of making decisions and developing an approach to help him become a responsible human being.” (Stanton E. Samenow, Ph.D., in “The Criminal Personality”) A Closer Look at the Research from Indian Country Native American Gangs The following information is from research conducted by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), U.S. Department of Justice, taken from “Youth Gangs in Indian Country”, a Juvenile Justice Bulletin, March 2004, and the 2000 Survey of Youth Gangs in Indian Country Native American Gangs To address appropriate social issues and cultural sensitivity, advisors from the following were consulted for the study: National Youth Gang Research Staff Researchers from Center for Delinquency and Crime Policy Studies Representative from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) The Department of Justice Department of Housing and Urban Development Department of Health and Human Services Indian Health Services National Indian Court Judges Association National Congress of American Indians Tribal Leader as Initial Contact Instead of Law Enforcement Native American Gangs Law Enforcement Services: Vary from community to community Limited Resources (e.g. officer to resident ratio) Lack of sufficient crime data for these communities Native American Gangs Youth Gang Activity: Twenty-three percent of respondents (69 tribes) reporting having actives gangs in their communities during 2000. Seventy percent reported there was no gang activity and seven percent could not make a determination. Of Importance: The 23% mentioned approved were larger Indian country communities with greater gang involvement. Native American Gangs By contrast, law enforcement agencies responding to the same survey reported 40 percent of tribal jurisdictions with active gang involvement. The majority of respondents reported 1-5 different youth gangs in their communities. Half of the respondents said gang problems began after 1994, suggesting a relatively recent onset of gang activity. Native American Gangs Navajo Nation Field Study (2002) found that the importation and spread of youth gangs are the result of several factors: Frequency with which families move off and on the reservation Poverty Substance Abuse Family Dysfunction Cluster Housing verses Traditional Single-Family Housing Waning Connection to Native American Culture and Traditional Kinship Ties Among Cousins Native American Gangs “These changes in structural forces weaken families, schools, and other institutions traditionally associated with social control, thus allowing youth to be socialized on the street by gangs.” (from Armstrong, T.L., Bluehouse, P., Dennison, A., Mason, H., Mendenhall, B., Wall, D, and Zion, J. Finding and knowing the gang nayee-Field initiated gang research project: The judicial branch of the Navajo Nation, 2002) Native American Gangs Additional Statistics: Gangs in Schools: Eighty-six percent of Indian country communities with gang problems reported gang activity in the schools. This resulted in higher levels of violent victimization, availability of drugs and students who carry guns. Native American Gangs Criminal Involvement: 56 percent of respondents reported that youth gangs committed crimes both within and outside the community. 36 percent reported only crimes within Indian country. 47 percent of communities with a gang problem reported a significant graffiti issue; 40 percent reported vandalism; 22 percent reported drug sales; and 15 percent report aggravated assault. Native American Gangs Program and Policy Implications: “Survey findings suggest that the most critical concerns in Indian country communities are the social problems that contribute to youth gang involvement, not the gangs themselves. Respondents identified a variety of factors that promote delinquent behavior and gang activity, including parental apathy, erosion of family structure, low self-esteem, social problems in the community, and lack of positive activities for youth.” Native American Gangs “…programs incorporating a range of strategies to prevent, control, and reduce youth crime in Indian country could effectively combat gangs…” Prevention, Intervention, and Suppression Strategies with Programs that have Proven Success IMPROVING THE VISION OF OFFENDERS “Looking for their glasses” Nearsightedness (look in the mirror/not pleased with the view) Through Rose Colored Glasses Creating Shatter-Resistant Lenses Daily Wear Contacts Focusing Field of Vision Finding Contact Lenses “Four Eyes”/Role of Mentors Blindness/Finding the Way Color Blindness Is there a prescription for all offenders? © J. Gordon Swensen The Five I’s of Involvement (Working Towards a Solution) I. IDENTIFICATION- Finding the offender affected by the social diseases of delinquency, violence, substance abuse, and/or poor life choices II. ISOLATION- Separating the offender from the harmful influence III. INOCULATION- Vaccinating with “surround services” to eradicate the spread of illness IV. INCUBATION- A period of protected preparation for entry into a healthier existence V. INTEGRATION- Moving the offender into a more productive, healthier, lifestyle, including employment ©J. Gordon Swensen “Surveys conducted by the NIC’s (National Institute of Corrections) Transition and Offender Workforce Development Division among offender workforce development specialist trainees indicated that approximately 65% of offender workforce practitioners have received no formal training in offender workforce development.” (35th IRI Monograph, Moore, Carter, Simpson, & Wade) Professional “Tricks of the Trade”- the Things That Work Adjust the dials on your ‘Paradigm Viewmaster’ Treat offenders with respect-Have no ‘fear of fair’ Develop rapport carefully and caringly Respect is deserved, trust is earned Watch for ‘games criminals play’/don’t be manipulated Become culturally informed (those ‘native nuances’) See the offender through Superman’s lenses (beyond the mask) Channel productive, yet illegal skills into marketable ones Identify the possible disabilities behind, or affected by, the conduct Provide a way out of crime/break the cycle Search for answers in the scattered pieces of a family’s puzzle “Tricks of the Trade” (continued) Avoid the ‘Big Picture’-focus on the rainbow’s path instead of the pot at the end of it Talk ‘straight up’ with offenders/test their realities Don’t try to save the Titanic alone…trust the advice of those with sturdy lifeboats Change the expectation, and you change the destination Be specific in vocational planning (short-term objectives, key players, evaluation and time-lines) Advocate for offender employment with employers, the community, and lawmakers (more harvests/fewer obituary columns) Educate employers about disability and delinquency Gate-keepers and Key-Masters Let’s Talk Offender Re-Entry in Indian Country Are there strategies that work? How to collaborate with state and federal partners? An Example of a Partnership That Works This information comes from the document “Strategies for Creating Offender Reentry Programs in Indian Country”, American Indian Development Associates, prepared for the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Washington, D.C., August, 2010 Tribal Challenges with Offender ReEntry “Indians and non-Indians may have different perceptions of wrong-doing and the most effective means to address crime. In the non-Indian community, a person who commits a crime is deemed a law breaker who must be punished. Many Indian communities, however, traditionally view offenses as misbehavior that calls for corrective action or mentoring or an illness that requires healing.” Tribal Challenges (Continued) “The clash between worldviews and practices becomes evident in correctional facility construction, operations, programming, and reentry planning for offenders, which lack cultural relevancy. “…jails in Indian Country frequently operate under substandard conditions.” “A U.S. Office of Inspector General study found that Indian jails are understaffed, overcrowded, and underfunded.” “The poor conditions, lack of programming, and transitional services of BIA and tribal jails require vast improvement to support offender success in addressing the root causes of their incarceration.” State Challenges “Tribal-state relations vary among tribes from progressive to non-existent.” “For most tribes, state law enforcement is limited for tribal apprehension or prosecution.” “The lack of formal relations between tribal and state criminal justice authorities compromises justice for victims and tribal communities.” State Challenges (continued) Lack of tribal-state relationships prevents Involvement of tribal criminal and juvenile justice representatives , who could assist in all aspects of transitional planning. Proper notification by state authorities to tribal authorities that the state is housing or will release an Indian offender. Service agencies from coordinating and collaborating to develop an offender rehabilitation or care plan and assist with reintegration. Tribal justice and other service agencies from remaining in contact with tribal members serving sentences in offreservation prisons or facilities. Federal Challenges “Federal prisons or contracted correctional facilities often lack… Formal relationships with tribal criminal justice authorities. Tribal involvement in planning the return of Indian offenders. Notification policies or procedures to inform tribal authorities that they have custody of a tribal citizen or that an ex-offender is returning. Culturally relevant care or services. Culturally competent staff to assist ex-offenders in obtaining supportive services. “Reentry is a process and not an event. It necessitates that tribes resolve reentry issues with culture-based methods and approaches to integrate offenders back into their tribal communities.” “Reentry is not limited to the physical process of how offenders will return to their families and communities, but also includes how various stakeholders and partners will assist with transitional services and discharge planning; arrange for structured services to support ex-offenders and their families; and ensure victim and community protection and safety.” Strategies to Develop Tribal Reentry Programs “Identify stakeholders and providing the rationale as to why they should participate in reentry. Defining the roles of participating stakeholders. Articulating the stakeholder benefits for participation in reentry. Understanding the challenges for stakeholder participation. Identifying the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed by stakeholders to participate in reentry programs. Identifying the resources needed for a reentry program or initiative. Playing Nice in the Sandbox The state agency and AIVRS agency partnerships are varied and reflect the culture of each state agency and the culture of the various American Indian Rehabilitation Vocational Rehabilitation Service (AIVRS) agencies within those states. Quality collaboration is just like VR, it is a process. The collaborative process is not quick and easy, it must start with a will to persist regardless of how rocky the start and/or what the history may be like. Each partner must work to develop an understanding as to the needs and requirements of the other. The partners must take time to develop a relationship of respect. Partners need to communicate clearly and honestly. Set attainable goals or objectives to begin with and be willing to be patient… (from 10/4/11 National Clearinghouse of Rehabilitation Training Materials webinar) Advantages to Collaboration Leverage resources Create opportunities for efficiency Standardization Increased communication and cooperation between agencies (joint benefits) Cooperative problem-solving Impact recidivism and decrease costs Diplomacy, Partnering, and Collaboration Big Words that can equal Big Outcomes Negotiation, Teamwork, and Sharing When Orchestrated Carefully Can Impact the Bottom Line of Services to Offenders It is All About Team, Not About Turf Creating Pathways of Promise: Sustaining the Project for the Future Returning to the Reservation NO WORK IS INSIGNIFICANT! “All labor that uplifts humanity has dignity and importance and should be undertaken with painstaking excellence. If a man is called to be a street sweeper, he should sweep even as Michelangelo painted, or Beethoven composed, or Shakespeare wrote.” - Dr. Martin Luther King Making It Work Some Key Strategies for Partnering Between Programs Overcoming Barriers/Finding Common Ground Communication and Problem-Solving Dealing with Change The Political Climate Paradigm Shifts The Establishment of Trust Identifying a Liaison Understanding the “Common Goal” Making It Work Are There Additional Strategies to Consider? Everyone Wins…Especially the Client Critical to Maintain Focus on the Client Evidence of Collaboration Between 121 Projects and State Agencies Critical to Refunding Those Programs Make No Assumptions Collection of Data Data Information Sharing Being Able to go to the Tribes Relationship Building and Rapport Frequent Opportunities to Exchange Information Making It Work Strategies (continued): Getting Past the “Native Nuances” (cultural differences) Being Visionary and Forward-Minded Avoiding Turf Issues Looking for Additional Partners The Value of a Memorandum of Understanding Administrative Buy-In Efforts and Constant Work on the Partnership Making It Work Strategies (continued): The Art of Diplomacy and Negotiation Being Able to Go to the Tribes/Outreach Relationship Building and Rapport Cultural Competency Development (where needed) Learning to “Walk Your Talk” “eye of god” (Helix nebula) The Value of Perspective: Seeing the World Through a Different Lens Making Sense of the Needs of Those Around You Improving One’s Vision Allowing for Differences Finding Commonalities Landscape Changes Focus on What Matters Most Improving the Hood (aka “The Rez”) One Gang Member At A Time The Value of a Partnership Politics and Diplomacy Turf and Agendas Finding the Right Folks Not Business As Usual Trust and Accountability Improving the “Rez” One Gang Member At A Time Looking for “Buy-In” Principles and Practice Relationship-Building Seizing the Opportunities Streamlining Pathways Actions…Not Words… Always Remember: Working Together Can Be A Good Thing When Working With Gang Issues…Always Work In Large Groups… And If That Doesn’t Work… Questions?