Fiscal Management in Oil-Producing Countries

advertisement

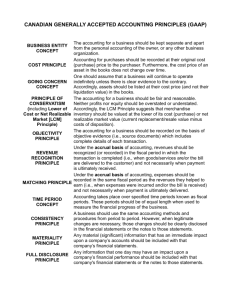

Oil Revenues and Fiscal Policy Philip Daniel Fiscal Affairs Department International Monetary Fund The PRMPS/COCPO Training Workshop The World Bank May 2007 The views in this presentation are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the International Monetary Fund, its Executive Board, or its management. Oil Revenues and Fiscal Policy Overview Challenges posed by oil revenue Fiscal policy and macroeconomic stability The non-oil primary balance Fiscal policy and intergenerational issues Oil funds Expenditure management Some guidelines Oil-Producing Countries Differ Importance of oil in the economy and fiscal accounts Development of the non-oil economy Maturity of the oil industry / oil production horizon Ownership of oil industry Fiscal regime for the oil sector Macroeconomic situation Financial position of the government and the public sector (gross and net debt, liquidity) Quality of institutions Petroleum Revenues and Stabilization Uncertainty and Instability Uncertainty about value of resource and timing of revenues Instability caused by volatility of oil prices Taxes must respond robustly to realised outcomes Stabilization Stabilize by total expenditure and revenue management, not by reliance on “stable” taxes General economic stability Reduces investors’ risk premia Avoids disruption of projects Strengthens negotiating & trading position Vital to poverty reduction Crude Oil Spot Prices, 1970-2006 1/ A Rollercoaster Ride 110 Real oil prices 100 90 80 U.S. dollars per barrel 70 60 50 40 30 Nominal oil prices 20 10 0 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 Sources: IMF, World Economic Outlook (Washington, various issues); and IMF staff estimates. 1/ Average of U.K. Brent, Dubai, and West Texas Intermediate. Real oil prices deflated by the US CPI (December 2005 = 100.) 2005 Guidelines for Stability Keep public sector demand in line with sustainable rate of capacity growth Save excess petroleum revenues abroad Use conservative price forecasts Save foreign assets in boom periods, use in downturns No need to “fine tune” the economy Rely on automatic stabilizers Oil funds are no substitute for sound fiscal management. The Non-oil Primary Balance Key fiscal indicator in petroleum exporters. Derived from the overall fiscal balance, excluding oil-related revenues & expenditures and net interest. Ideally, should include explicit or imputed expenditure on petroleum product subsidies if applicable. Analytical importance of the non-oil primary balance: Reasonable indicator of domestic government demand Measure of injection of oil revenue into the economy Measure of fiscal effort and underlying fiscal policy stance Key input into fiscal sustainability and intertemporal analysis Size of the Non-oil Primary Deficit Some factors to take into account: macroeconomic objectives short-run vulnerability government wealth, including oil in the ground and net accumulated financial assets—sustainability In some petroleum exporters, large non-oil primary deficits are sustainable and do not pose vulnerability concerns. In others there may be a need to reduce the non-oil primary deficit due to vulnerability and sustainability considerations. In all cases, the non-oil primary deficit should be consistent with macroeconomic stability objectives. Smoothing Fiscal Policy: Fiscal Considerations (1) Costly and inefficient to adjust spending rapidly and abruptly. The level of spending should be determined in light of its likely quality and the capacity to execute it efficiently. The sudden creation or enlargement of spending programs is risky. Increases in spending may exceed the government’s planning, implementation, and management capacity waste. Spending should not rise faster than transparent and careful procurement practices will allow. Smoothing Fiscal Policy: Fiscal Considerations (2) Spending typically proves difficult to contain or streamline following expansions. Expenditure becomes entrenched and takes a life of its own. Drastic spending cuts may lead to social instability, discouraging investment and reducing future growth. The Non-oil Primary Balance and Transparency Focus on the non-oil primary balance helps develop constituencies in support of prudent policies, thereby contributing to a less procyclical and more long term-oriented fiscal policy. This balance should be highlighted in budget documents used in parliamentary and public discussion. A clear presentation of the non-oil primary balance helps: Make the use of oil revenue more transparent Delineate policy choices more clearly Example: Norway’s budget. Long-Run Oil and Fiscal Dynamics: Trajectory of Net Government Wealth Total net wealth per capita (In 1997 U.S. dollars) 16000 14000 12000 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 1998 2003 2008 Oil wealth 2013 2018 2023 Residual oil in the ground 2028 2033 Financial assets 2038 A Path for Use of Oil Revenues: Permanent Income The Concept Current consumption limited to maintain wealth for future generations Sustainable use – resources converted to other incomeproducing financial assets A guideline with uncertainties Advantage of making intergenerational equity an explicit goal The Calculation Petroleum reserve data & production profiles Production cost or state take Output price forecasts Real interest rate Population growth rate Subtract discounted present value (adjusted for population growth) from total real revenues Oil Funds Purposes Stabilization– shield economy from revenue instability Savings – wealth for future generations Precautionary – if projects are uncertain or absorptive capacity is in doubt Links with Fiscal Policy Oil funds are no substitute for good fiscal management; important producers operate without oil funds (UK, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Australia, Russia) Important features 1. 2. 3. Consolidated budget framework Liquidity constraint on the budget Limits on domestic investment by the oil fund Types of Oil Funds, by Objective Stabilization Funds Savings Funds Precautionary Funds Receive all revenues & inject regular amounts to budget [Papua New Guinea – wound up 2000] Petroleum revenues in excess of forecast budget amount [Oman] Fixed percentage of petroleum revenues [Alberta, Alaska] Assign all or part of revenues to fund in early stages of petroleum development Percentage of total government revenue [Kuwait] Goal to ensure financial viability if revenues are lower than expected Finance deficit or receive surplus [Norway] Net government revenues (budget surplus) [Norway] Guards against poor absorptive capacity Receive deposits above a reference price; can withdraw when below floor price [Chile, Venezuela until 2001] Recent examples in Azerbaijan and Timor-Leste [now a Norway-type fund] Types of Oil Fund, by Operational Rules Contingent funds Revenue-share funds Mainly stabilization objectives Deposit and withdrawal depend on rigid exogenous triggers, usually oil prices or fiscal oil revenues. Triggers: multiyear (fixed/moving average) or intra-annual (relative to budget oil price) Examples: Venezuela Macroeconomic Stabilization Fund (1998 rules), Iran Mainly savings objectives A fixed share of revenues or oil revenues is deposited in the oil fund. Various rules (or discretion) for withdrawals Example: Kuwait Reserve Fund for Future Generations Financing funds Both stabilization and savings objectives Net oil revenue is deposited in the fund. The fund automatically finances the budget’s non-oil deficit through a reverse transfer. Example: Norway Government Pension Fund Fund Management Potential for poor management with or without oil fund: Key elements for efficiency of oil fund – Regular public disclosure Accountability to elected representatives Independent audit of activities Clear investment strategy – majority foreign assets “Benchmarking” of desired investment returns Competition in appointment of investment managers Oil Funds, PFM, and Transparency Oil funds should not have the authority to spend avoid dual budgets: all spending should be transparently on budget. Oil revenues should not be earmarked for specific expenditures there should be genuine competition for fiscal resources. Avoid separate oil fund institutional frameworks Stringent mechanisms to ensure good governance, transparency, and accountability are critical clarity of rules, disclosure, audit, and performance evaluation The Need to Distinguish Oil Funds from Fiscal Rules Oil funds are sometimes confused with fiscal rules. Oil funds do not constrain fiscal policy—unless the government is liquidity-constrained. Fiscal Rules in Oil-Producing Countries Attempt to insulate fiscal policy from political pressures. By placing restrictions or limits on fiscal variables (such as deficits, expenditure, debt), rules seek to constrain fiscal policy. Design of fiscal rules in oil producers must take into account their specific fiscal characteristics (oil volatility; expanded concept of sustainability). Rules should aim at decoupling expenditure and the non-oil deficit from the short-term volatility of oil revenues. But many oil producers are liquidity-constrained—can these countries afford to decouple spending in the downswing? A sound fiscal management framework is a necessary (not sufficient) condition for the success of a fiscal rule. Fiscal rules are no stronger than the will of the political class to abide by them. Medium-Term Expenditure Frameworks MTEFs can help limit the extent of short-run spending responses to rapidly-changing oil revenues. They can allow a better appreciation of future spending implications of current policy decisions—including future recurrent costs of capital spending. Expenditure Public Expenditure Management No special rules for expenditure from petroleum revenues Consistent base data Budget preparation procedures Budget execution system Cash planning and management Extra-budgetary funds Better mobilization of public support? Simulate market conditions? Disadvantages Loss of central control and budget integrity Resource allocation distortion Entrenching old priorities Barrier to reallocation at the margin Potential transparency concerns Attempts in special circumstances proved difficult (Chad example) Final Remarks Target smooth responses of expenditure to oil revenues and prudent nonoil primary balances. Fiscal consolidation may be needed to reduce vulnerability and strengthen fiscal sustainability. Pay attention to the non-oil primary balance and scaling factors. Establish sound budgetary systems. Have a long-term horizon. Enhance fiscal transparency, so that everybody can see how oil revenue is used—or misused.