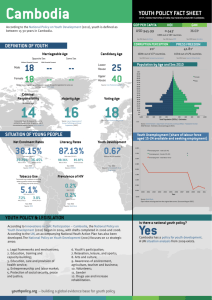

Cambodia Paper 5

advertisement