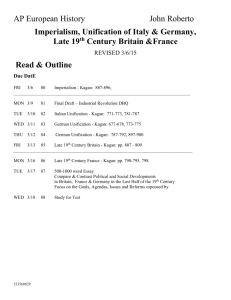

Research

advertisement

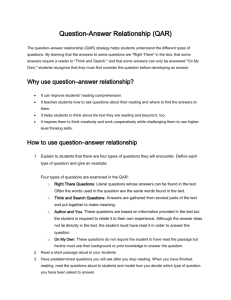

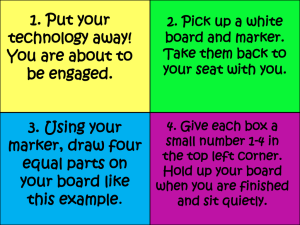

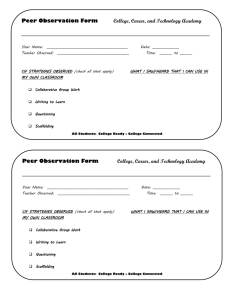

The Quest for Higher-Order, Student-Generated Questions Presented by: Jenn Maher SNWP Fall Conference, 2011 1 Research Making Content Comprehensible for English Language Learners, by Jana Echevarria, MaryEllen Vogt, and Deborah J. Short (2004) Engaging Readers and Writers with Inquiry, by Jeffrey Wilhelm (2007 and What’s the BIG IDEA? Question-Driven Units to Motivate Reading, Writing, and Thinking, by Jim Burke (2010 2 Outlines a set of protocols for teachers of English Language Learners, called the “Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOP) Breaks the concept of scaffolding into three types: verbal scaffolding through paraphrasings and think-alouds; procedural scaffolding through various grouping strategies and a gradual release towards student independence; and instructional scaffolding with the use of graphic organizers, and cueing systems Advocates careful planning for student interactions and discussions through various grouping strategies and the opportunity to write extended responses to questions Argues that our English Language Learners need to be engaged with higher-order thinking skills and recommends using the Question-Answer-Relationship questioning scheme QAR’s in the classroom. Student literacy practices need to be grounded not only in the state-mandated curriculum, but also in student interests and personal dilemmas. Student engagement is increased when students see a reason and purpose in an activity. Literature is a powerful tool for providing insights about yourself and life in general. Classroom discussions improve reading comprehension. Students should be provided with various questioning schemes to scaffold their own questions: o Question-Answer-Relationships (in packet) o Socratic Seminars o Questioning the Author (packet) o ReQuest (packet) o The Questioning Circle o Hillock’s Questioning Hierarchy (packet) All students will achieve in reading comprehension and writing if effective scaffolding is used for difficult tasks. After students write their questions, they should also be asked to explain why their questions are important and relevant to the topic being discussed. Lesson Plan for Scaffolding QAR’s This lesson is adapted from a classroom activity described by Kylie Elizabeth Meyers in her article title “A Collaborative Approach to Reader’s Workshop in the Middle Years”, The Reading Teacher,63(6) p 501-507 (March 2010). I modified it by pulling in specific Kagan structures that I thought would help scaffold QAR’s for my ELL’s. Content Objective: Categorize questions according to the Question-Answer-Relationship schema Evaluate whether or not a question is a good discussion question Reflect on what makes a question a good discussion question Language Objectives: Write questions with or without question frames Discuss the catagories that questions fit into. “I think that________ fits ___________ because… Revise questions as needed Justify in writing the value or importance of a question Previous learning experiences: Teacher modeling of asking questions through think-alouds Introduction to the QAR schema – teacher modeling of each type of question, students search through textbooks in pairs to identify question types, whole-class generated lists of sample questions Materials: short text as a read-aloud or copies for the students, post-it notes, whiteboard and markers, masking tape to mark off desks into four quadrants, reader’s notebooks, previous posters made by the class, a question matrix generator Activities: 1. Read a short text aloud to students, or provide them with a short text to read themselves. 2. “Jot Thoughts” activity from Kagan (2004) – Place students in groups of four. Give each student a stack of post-it notes. In three minutes, students brainstorm as many questions as they can about the text. Students read each post-it note to their group as they finish. There is no turn-taking, just the writing and reading of questions. THE GOAL IS TO GENERATE AS MANY IDEAS AS POSSIBLE AND COVER THE TABLE. 3 3. Collect a question or two from each group. Divide the whiteboard into four quadrants for the four types of questions in a QAR. Read the collected questions aloud to the class and identify the type of question each is. Place it in the right quadrant. 4. Round Robin Consensus (Kagan, 2004) – Students take turns picking up a question, identifying its category, and explaining why it should go there. Group members can dissent or agree with the placement, but consensus must be reached before the post-it note is placed in a quadrant. 5. Groups report out a question and placement to the whole class; teacher records. 6. If tables notice any question-types that are missing, they may be given time to think-writeround-robin share new questions. 7. Teacher chooses one student question. Teacher models how to think in writing to the following prompt: Is this question important? Is it worth asking of other people? Does it contribute help to make sense of the text we have just read? Does it make us think? 8. Students then select a question that they think is particularly strong and that they would like to see used in a classroom. Students copy the question into their reader’s notebooks, and then reflect in writing: Why is this question important to the text? Is it worth asking of other people? Why or why not? 9. Stand-Up-Hand-Up-Pair-Up (Kagan) Students stand and find a partner outside of their group. They place hands together so that the teacher can see pairs and help direct lost students. Students share their questions and their reflections, and then try the questions out on each other to see if they really do yield strong answers. 10. Whole-group closure: Students share and the teacher lists: What are the qualities of a good question? 11. Follow-up: provide a new piece of text. Ask students to write QAR questions. Students should decide which questions are truly important and have value in a discussion. They should explain why in writing. 4 Annotated References Blumenreich, M. and Falk, B. (2005). The Power of Questions: A guide to Teacher and Student Research. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann This book helps to lay a strong foundation for anyone wanting to engage in action research. It covers everything from framing your teaching dilemma as a question, to writing through your own personal assumptions associated with the dilemma, to the logistics of gathering and collecting qualitative data. It also includes information about creating space and supporting your students’ questions. Burke, J. (2010). What’s the Big Idea? Question-Driven Units to Motivate Reading, Writing, and Thinking. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann From the foreword, written by Arthur Applebee: “Jim …goes on to show us how a focus on big ideas and enduring questions can, over extended periods of time, add depth and rigor to the curriculum, while simultaneously increasing student interest and engagement.” I think that says it all. Echevarria, J., Short, D., and Vogt, M. (2004). Making Content Comprehensible for English Language Learners: The SIOP Model. Boston, Massachusetts: Pearson. This is a must-own for all teachers of English Language Learners. It breaks outlines the protocol for designing and implementing lessons with the English Language Learner in mind. It also has various teaching vignettes that you can evaluate for ELL effectiveness. Kagan, S. and Kagan, M. (2009). Kagan Cooperative Learning. San Clemente, California: Kagan Publishing Once I decided that what I needed to do was do a better job scaffolding my lessons for my English Language Learners, I turned to my Kagan materials for support. It is one of those practical guides for creating structure in a classroom lesson. Marzano, R., Pinkering, D, and Pollock, J. (2001). Classroom Instruction that Works: Research-Based Strategies for Increasing Student Achievement. Alexandra, Virginia: McRel Publishing. Marzano discovered that effective questioning practices in the classroom could potentially yield a measurable increase in student achievement. In the various studies that he and his colleagues reviewed, they determined that questions, cues, and organizers could lead to a twenty-two percent gain in student achievement. Marzano observed that “higher-level questions produced deeper, more enduring learning than “lower-level” questions. Marzano was referring to the types of questions that teachers ask of students, not studentgenerated questions. 5 Meyer, Kylie Elizabeth (March 2010). A Collaborative Approach to Reading Workshop in the Middle Years. The Reading Teacher 63(6) p. 501-507 Kylie Elizabeth Meyer showed how she structured QAR activities so that students were more successful in the generation of “Think-and-Search” and “Author-and-Me” Questions. My favorite part of her article was how she then analyzed her students’ questions as her formative assessment and used it for planning follow-up lessons in reader’s workshop. She grouped her students’ questions into categories: questions that showed a lack of pragmatic competence with a text; questions that showed a lack of semantic competence; questions that showed a lack of vocabulary competence; and questions that showed a lack of critical competence. This grouping was based on the work of Freebody and Luke, something I will definitely investigate later on. Wiggins, G. and McTighe, J. (2005) Understanding by Design. Columbus, Ohio: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall I had a momentary flash of insanity and decided to reread Understanding by Design, by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe (2005). I found this book difficult to get through the first time around and I am not quite sure why I was willing to submit myself to it again. But the second reading helped me to refocus my philosophy on the inquiry process of the classroom. It reminded me of the importance of framing the curriculum with essential questions that are meaningful and relevant to my students. Wilhem, Jeffrey (2007) Engaging Readers and Writers with Inquiry. New York: New York: Scholastic This books is amazing! It is filled to the brim of various questioning schemes and examples of how to use them with students. The examples span the grade levels, K – 12, so it is easy to see how to use the strategies in your own classroom, Websites International Baccalaureate Program. http://www.ibo.org/ Accessed 6/2/10 The Story of Stuff. http//www.storyofstuff.com Accessed 6/2/10 The SIOP Model: Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol http://www.siopinstitute.net/classroom.html Accessed 11/3/11 International Reading Association. http://readwritethink.org Accessed 11-3-11 6 Hillocks’ Questioning Hierarchy Basic Stated information — information taken directly from the words on the page. Key detail — information implied by the words on the page. Stated relationship — information given by the author about a variety of stated information. Simple implied relationship — information supplied by the author, but not stated. Complex implied relationship — inference; not directly stated, but implied. Author’s generalization — what the author is trying to say about everyone (the people outside the text. Structural Generalization — How it’s all put together to elicit our response. “> What does Calvin’s dad think Calvin needs? What has happened to the snowman on the ground? What season is it? What’s going on in this picture? Who did the snowman sculpture? How does each snowman feel about what has happened to the one on the ground? What clues do you see? How does dad feel about what he sees? How does the mom feel? What clues you into your answer? What happened before this panel? Whose house does this take place? What does the author say about the way parents react to their child’s/children’s actions? What does the author say kids do when their parents aren’t around? What does the author think about how we normally make/pose snowmen? Why is this told in just one panel? What does the cloud behind the dad’s head signify? Notice the difference between mom’s and dad’s eyebrows—what expression is each on wearing?http://thereflectiveteacher.wordpress.com/2006/11/17/answering-questions%E2%89%A0-learning/ 7 Questioning the Author (QtA) There are three main types of queries: initiating, follow-up, and narrative. Within each of these main types of queries there are specific prompts that are used to help launch a discussion, focus students in a specific area of the content, or focus students on a particular characteristic of the text. It is important to remember that query prompts should be used during the reading of a text. Initiating Queries Three types of suggested Initiating Queries include: o o o What is the author trying to say here? What is the author’s message? What is the author talking about? These types of prompts will help make text ideas public and prepare your students to construct meaning of the piece of text they are reading. Remember, this is to be done as you work through the text, not at the end of an assigned reading (Beck, et al., 1997). Follow-Up Queries Follow-up queries help focus the content and direction of the discussion. The goal is to help students look at "what the text means rather than what the text says" (Beck, et al., 1997, p. 37). Some follow-up prompts that can do this are: o o o o o o What does the author mean here? Does the author explain this clearly? Does this make sense with what the author told us before? How does this connect to what the author told us here? Does the author tell us why? Why do you think the author tells us this now? Narrative Queries Narrative queries are used because narrative texts have different characteristics than expository text in terms of structure, authorship, and purpose. Queries may often deal with characters, theme, and plot. Some useful prompts for this type of query include: o o o o How do things look for this character now? Given what the author has already told you about this character, what do you think he’s up to? How has the author let you know that something has changed? How has the author settled this for us? Accessed 6/13/10 http://forpd.ucf.edu/strategies/stratQtA.html 8