Powerpoint Version - S

advertisement

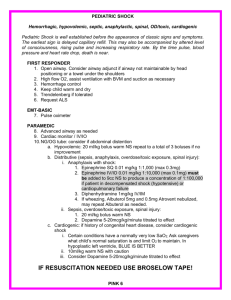

Sierra – Sacramento Valley EMS Agency 2015/2016 REGIONAL TRAINING MODULE S-SV EMS Agency 2015/2016 Regional Training Module ▪Training Module Agenda: ▪ S-SV EMS Agency General Trauma Management Treatment Protocol (T-1) Spinal Stabilization Updates ▪ Sepsis ▪ Advanced Airway Management S-SV EMS Agency 2015/2016 Regional Training Module ▪Training Module Objectives: ▪ Participants in this course will learn the following: ▪ The history, facts and current guidelines related to prehospital spinal immobilization/stabilization ▪ S-SV EMS Agency General Trauma Management policy (T-1) updated spinal stabilization guidelines ▪ Prehospital assessment and treatment of sepsis patients ▪ Advanced airway management education/training that will: 1. Maximize first time attempt success 2. Reduce transient hypoxia and improve patient outcomes 3. Reduce complications, such as unrecognized esophageal intubation Spinal Stabilization Spinal Stabilization ▪History of Spinal Immobilization ▪ A key feature of early EMT training Spinal Stabilization ▪History of Spinal Immobilization ▪ 1960s: Growing awareness of spinal injuries ▪ “The most frequently mishandled injuries, made worse by hasty and rough movement from a vehicle or other accident scene, are fractures of the spine and the femur.” - J.D. Farrington, MD, from DEATH IN A DITCH, American College of Surgeons, 1967 Spinal Stabilization ▪History of Spinal Immobilization ▪ Early spinal injury research ▪ A 1963 survey of a large series of patients with fatal injuries treated at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary showed that 25% of fatal complications occurred during the period between the accident and arrival in the ED ▪ This statement was taken by several papers at the time to imply that up to 25% of spine injuries worsened because of improper EMS packaging and handling Spinal Stabilization ▪History of Spinal Immobilization ▪ Early spinal injury research ▪ A 1965 retrospective study of 958 spinal cord injury patients in Toronto attempted to quantify serious cord damage due to “inept handling of the patients” ▪ Only 29 patients (3%) had “incontrovertible” evidence of delayed paralysis, attributed to either pre- or in-hospital inept handling ▪ Authors suspected but could not prove that “a larger number undoubtedly suffered this fate” Spinal Stabilization ▪History of Spinal Immobilization ▪ Early spinal injury research ▪ In 1966, USAF Col. L. C. Kossuth first described the use of the long backboard to “move a victim from the vehicle with a minimum of additional trauma” ▪ Such movement was to occur with “due regard to maximum gentleness” Spinal Stabilization ▪History of Spinal Immobilization ▪ Approximately five (5) million patients are immobilized in the prehospital environment in the U.S. each year ▪ Most have no complaints of neck or back pain or other evidence of spine injury Spinal Stabilization ▪The Facts ▪ Greater than 50% of trauma patients with no complaint of back/neck pain get full spinal immobilization ▪ 13% get immobilized without being asked about pain ▪ Less than 2% of EMS patients per year with suspected c-spine injury have a fracture ▪ Less than 1% develop neurological deficits Spinal Stabilization ▪Why Initiate Spinal Stabilization? ▪ 253,000 people in US living with spinal cord injuries ▪ 12,000 new cases each year ▪ In the US, the cost of MVA related spinal cord injury is estimated to be $34.8 billion per year Spinal Stabilization ▪Epidemiology of Spinal Cord Injuries ▪ 77.8% males ▪ Average patient age when injury sustained: ▪ 28.7 years old in 1970’s ▪ 39.5 years old in 2005 ▪ Causes: ▪ MVC – 42% ▪ Falls – 27% ▪ Violence – 15% ▪ Sports – 7.4% Spinal Stabilization ▪In some cases, spinal immobilization may not be in the patient’s best interest ▪“Prehospital spine immobilization is associated with higher mortality in penetrating trauma and should not be routinely used in every patient with penetrating trauma”1 ▪2001 Large meta-analysis on spinal immobilization ▪ “Effect on mortality, neurologic injury, spinal stability… uncertain.” ▪ “Possibility that immobilization may increase mortality and morbidity cannot be excluded” 1Spine immobilization in penetrating trauma: more harm than good?, J Trauma. 2010 Jan; 68(1):115-20 Spinal Stabilization ▪Backboards Cause Pain ▪ 1989 study of 170 trauma victims eventually discharged from a major ED showed a significant reduction in c- and lspine pain when patients were allowed off the boards ▪ 21% had cervical pain/tenderness on the board but not off, suggesting that the immobilization process or the boards themselves cause pain that otherwise would not be there ▪ 1993 study caused 100% of 21 healthy volunteers to report pain within 30 minutes of being strapped to a backboard • Headache, sacral, lumbar, and mandibular pain most common Spinal Stabilization ▪Backboards Cause Pressure Sores ▪ A 1988 prospective study at Charity Hospital of the association between immobilization in the immediate post injury period and the development of pressure ulcers in spinal cord-injured patients ▪ Time on the spinal board was significantly associated with ulcers developing within 8 days Spinal Stabilization ▪Backboards Cause Pressure Sores ▪ A 1995 study at Methodist Hospital of Indiana measured the interface (contact) pressures over bony prominences of 20 patients on wooden backboards over 80 minutes ▪ Interface pressure > 32 mm Hg causes capillaries collapse, resulting in ischemia and pressure ulceration. ▪ This study measured mean interface pressures as high as 149 mm Hg at the sacrum, 59 mm Hg at occiput, and 51 mm Hg at heels Spinal Stabilization ▪Backboards Cause Respiratory Compromise ▪ A 1987 study at Beaumont Hospital of healthy, backboarded males concluded that backboard straps significantly decrease pulmonary function ▪ Similar 1999 study showed 15% respiratory restriction in backboarded adult subjects ▪ 1991 pediatric study showed decreased forced vital capacity (FVC) in children due to backboard straps Spinal Stabilization ▪Other Concerns ▪ Cervical collars have been associated with elevations of intracranial pressure (ICP) ▪ Prospective study of 20 patients ▪ Significant (p = .001) increase in ICP from 176.8 to 201.5 mm H20 ▪ American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) 2001 Guidelines for Prehospital Cervical Spinal Immobilization following trauma: ▪ “There is insufficient evidence to support treatment standards” ▪ “There is insufficient evidence to support treatment guidelines” Spinal Stabilization ▪ 5 year retrospective chart review at University of New Mexico and University of Malaysia hospitals ▪ All 454 patients with acute spinal cord injuries included during the 5 year study period ▪ None of the 120 U. Malaysia patients were immobilized ▪ All 334 U. of NM patients were immobilized in the field • Hospitals and treatment otherwise equivalent • Results: 2x MORE neurologic disability in the University of New Mexico patients Spinal Stabilization ▪How well do we immobilize anyway? ▪ Convenience sample of 50 low acuity backboarded subjects at one Level 1 ED ▪ 30% had at least 1 point where a strap or tape did not secure the head ▪ 70% had 1 strap with >4 cm slack ▪ 12% had all 4 straps with >4 cm slack ▪ “At 4 cm, movement in any direction along the board is both possible and probable” ▪ A well secured head and mobile body creates movement of the neck Spinal Stabilization ▪How well do we immobilize anyway? ▪ Backboards don’t make patients lie still ▪ A violent or agitated patient is going to fight against a backboard, threatening his/her spine ▪ A cooperative patient is going to lie still when asked (or if it hurts to move), regardless of a backboard or straps Spinal Stabilization ▪How well do we immobilize anyway? ▪ Mock automobile was constructed to scale, and volunteer patients, with infrared markers on bony prominences, were extricated by experienced paramedics ▪ “Extricating the driver/subject headfirst by standard technique to a long spine board was associated with significant cervical spine motion, both with the collar alone and even with a cervical collar and KED” ▪ “Ultimately, we documented the least movement of the cervical spine in subjects who had a cervical collar applied and were allowed to simply get out of the car and lie down on a stretcher” 1Cervical Spine Motion During Extrication: A Pilot Study, West J Emerg Med. 2009 May; 10(2):74-78 Spinal Stabilization ▪1999 NAMESP Position Paper ▪ “There have been no reported cases of spinal cord injury developing during appropriate normal patient handling of trauma patients who did not have a cord injury incurred at the time of the trauma.” ▪ “Although early emergency medical literature identified mis-handling of patients as a common cause of iatrogenic injury, these instances have not been identified anywhere in the peer-reviewed literature and probably represent anecdote rather than science.” Spinal Stabilization ▪Summary ▪ We immobilize way too many patients ▪ Most injured patients will be mechanically stable ▪ Totally unstable patients probably have maximum damage at time of impact ▪ All immobilized patients can be potentially harmed ▪ Spinal immobilization is a misnomer ▪ Spinal Immobilization is a method of transport, not a therapy Spinal Stabilization ▪Latest Spinal Injury Guidelines ▪ In July, 2013, NAEMSP and ACS-COT released a joint position paper on “EMS Spinal Precautions and the Use of the Long Backboard” that indicated the following: ▪ Utilization of backboards for spinal immobilization during transport should be judicious, so that the potential benefits outweigh the risks ▪ Spinal precautions can be maintained by application of a rigid cervical collar and securing the patient to the EMS stretcher, and may be most appropriate for: ▪ Patients who are found to be ambulatory at the scene ▪ Patients who must be transported for a protracted time, particularly prior to interfacility transfer Spinal Stabilization ▪S-SV EMS Agency Protocol T-1 ▪ Patients with penetrating trauma to the head, neck or torso and no evidence of spinal injury should not be stabilized on a backboard Spinal Stabilization ▪S-SV EMS Agency Protocol T-1 ▪ Spinal stabilization with a backboard should be implemented for trauma patients who meet any of the following criteria: ▪ Midline spinal pain or tenderness ▪ Limited cervical spine active range of motion ▪ Gross motor/sensory deficits or complaints ▪ High energy impact blunt trauma patients meeting anatomical and/or physiological trauma triage criteria Spinal Stabilization ▪S-SV EMS Agency Protocol T-1 ▪ Spinal stabilization with or without a backboard should be considered for trauma patients who have an unreliable history & physical: ▪ Altered mental status (i.e. dementia or delirium) ▪ Intoxicated (drugs or alcohol) ▪ Injury detracting from or preventing reliable history & exam ▪ Language barrier preventing reliable history & exam ▪ Extremes of age < 5 or > 65 years old Spinal Stabilization ▪S-SV EMS Agency Protocol T-1 ▪ Initiation of spinal stabilization is not necessary for patients who do not meet any of the criteria listed on the previous 2 slides ▪ Helmet removal guidelines: ▪ Football helmets should not be removed unless they fail to hold the head securely, interfere with the airway, or prevent proper stabilization ▪ Note: If the helmet is removed, the shoulder pads should also be removed and/or the head should be supported to maintain neutral stabilization ▪ Motorcycle, bicycle, and other helmets should be removed Spinal Stabilization ▪Spinal Stabilization Without A Backboard ▪ By maintaining spinal precautions using the ambulance stretcher, we can protect the spine as best possible without the downside risks of the backboard ▪ The following are acceptable methods and tools to achieve spinal stabilization without a backboard: ▪ Fowler’s, semi-fowler’s, or supine positioning on stretcher with c-collar only ▪ Supine position with vacuum mattress device splinting from head to toe ▪ Child car seat with appropriate supplemental padding ▪ Supine positioning on scoop stretcher, secured with strap system and appropriate padding including head blocks – avoiding log roll movement adds benefit Spinal Stabilization ▪Self Extrication ▪ Start with normal cervical stabilization with manual techniques and collar Spinal Stabilization ▪Self Extrication ▪ If the patient is comfortable with self extrication, assist the patient with the process as needed Spinal Stabilization ▪Self Extrication ▪ Assist the patient as needed to exit the crash setting ▪ The patient’s effort and collar are used for cervical stabilization ▪ Addition manual stabilization is not needed Spinal Stabilization ▪Self Extrication ▪ Move the patient to the ambulance stretcher Spinal Stabilization ▪Self Extrication ▪ Place the patient in a position of comfort on the ambulance stretcher & secure with stretcher straps Sepsis Sepsis ▪Sepsis Facts ▪ There are 750,000 cases of sepsis in the US each year ▪ More than 2/3 are seen in the ED ▪ 10th leading cause of death in the US ▪ 250,000 deaths each year ▪ Mortality rate estimated at 25-50% ▪ Most common cause of death in non-coronary ICUs ▪ Greater than 1/3 of ED patients with infections, severe sepsis and septic shock receive their initial care from EMS ▪ Patients that arrive by EMS have higher mortality rate Sepsis ▪Sepsis Information ▪ Sepsis is a rapidly progressing, life threatening condition due to systemic infection ▪ Sepsis must be recognized early and treated aggressively to prevent progression to shock and death ▪ Sepsis can be identified when the following markers of the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) are present in a patient with suspected infection: ▪ Temperature > 100.4° F OR < 96.8° F ▪ Respiratory Rate > 20 breaths/min ▪ Heart Rate > 90 beats/min Sepsis ▪ETCO2 Assessment ▪ Severe sepsis is characterized by poor perfusion, leading to a buildup of serum lactate and resulting metabolic acidosis ▪ EtCO2 levels decline in the setting of both poor perfusion and metabolic acidosis ▪ As lactate levels rise in septic patients, ETCO2 levels drop ▪ In patients with ≥ 2 SIRS criteria, an ETCO2 measurement of ≤ 25 mmHg is strongly correlated with lactate levels > 4 mM/L and increased mortality Sepsis ▪Prehospital Sepsis Management ▪ Early identification and prehospital management can significantly decrease patients ICU stays, hospital stays and mortality ▪ S-SV EMS General Medical Treatment Protocol (M-6) is currently being updated to address assessment/treatment/ED notification ▪ Provide early hospital notification for suspected sepsis/SIRS pts ▪ Provide early and appropriate fluid resuscitation ▪ The goal of the fluid resuscitation is to get enough fluid in the vasculature to increase the BP enough to perfuse vital organs ▪ Unlike hypovolemic shock, septic shock doesn’t need more oxygen carrying fluid - Isotonic fluids are adequate, especially in the initial phases of treatment Advanced Airway Management Advanced Airway Management ▪Factors suggestive of the need for invasive airway management ▪ Apnea or agonal respirations ▪ Airway reflexes compromised (ventilatory effort adequate, e.g. unconscious without a gag reflex) ▪ Ventilatory effort compromised (airway reflexes adequate, e.g. pulmonary edema) ▪ Injury or medical condition directly involving the airway ▪ Adequate airway reflexes and ventilatory effort, but potential for future airway or ventilatory compromise due to course of illness (head or other), or medical treatment Advanced Airway Management ▪Additional Findings ▪ Increased respiratory rate ▪ Muscular retractions (suprasternal, intercostal, abdominal) ▪ Labored breathing ▪ Impaired speech ▪ Decreased level of consciousness ▪ Agitation ▪ Pallor or cyanosis ▪ Increasing end-tidal carbon dioxide (capnography) ▪ Inadequate oxygen saturation (pulse oximeter) Advanced Airway Management ▪Definitions ▪ Unsecured Airway ▪ A compromised airway in which ventilation is possible by Bag Mask but in which intubation has failed or has not been attempted ▪ Can’t intubate, can ventilate ▪ Uncontrolled (Unmanageable) Airway ▪ A compromised airway in which intubation has been unsuccessful after two attempts, rescue airways are unsuccessful, and in which BVM ventilation does not provide satisfactory oxygenation or ventilation ▪ Can’t intubate, can’t ventilate Advanced Airway Management ▪Advanced Airway Placement PEARL #1 ▪ “Getting the tube in is not the only goal when attempting to effectively manage an airway” ▪ Avoid aspiration, hypoxia, delaying CPR or defibrillation ▪ An endotracheal tube or rescue airway is just a method to supply oxygen and ventilate, sometimes basic airway management is best ▪ There may be adverse patient consequences for placing an advanced airway Advanced Airway Management ▪SOAP ME Mnemonic ▪ S – Suction ▪ O – Oxygen ▪ A – Airway ▪ P – Positioning ▪ M – Monitoring ▪ E – End-Tidal Carbon Dioxide (ETCO2) Advanced Airway Management ▪S – Suction ▪ Ensure that a suction unit with Yankauer suction tip is readily available Advanced Airway Management ▪O – Oxygen ▪ Saturation vs pO2 100 ▪ A drop in saturation can mean a precipitous drop in blood oxygen level ▪ Note how steep the curve drops with the saturation (SP02) important to maintain high level of O2 ▪ Pulse Ox on a distal extremity has a lag time of 60 – 90 seconds SpO2 (%) ▪ Maintain saturation above 90% in patients requiring supplemental O2 80 60 40 20 0 0 50 100 150 pO2 (mmHg) 200 250 Advanced Airway Management ▪O – Oxygen ▪ Procedure for maintaining adequate oxygenation during advanced airway procedures: ▪ Apply a nasal cannula with a flow rate of 5 - 15 L/min as tolerated ▪ If patient is breathing spontaneously and cooperative, apply an additional non-rebreather mask with a flow rate of at least 15 L/min, using a secondary oxygen source ▪ If possible, allow patient to breathe for three (3) minutes or ask the patient to perform eight (8) maximal exhalations and inhalations Advanced Airway Management ▪O – Oxygen ▪ Procedure for maintaining adequate oxygenation during advanced airway procedures (continued): ▪ Just prior to advanced airway placement, increase nasal cannula flow rate to 15 L/min and replace non-rebreather mask with BVM ventilation at appropriate rate ▪ Perform jaw thrust to maintain pharyngeal patency ▪ Apply advanced airway ▪ Maintain nasal cannula at a flow rate of 15 L/min until advanced airway is secured Advanced Airway Management ▪A – Airways ▪ Select & utilize appropriate advanced airway according to your scope of practice and individual patient circumstances ▪ Orotracheal Intubation ▪ Nasotracheal Intubation (utilizing Endotrol® ET Tube and BAAM) ▪ King Airway Device ▪ No more than two (2) total attempts per patient at placing the endotracheal tube ▪ Intubation attempt - introduction of an ET tube past the patient’s teeth ▪ If orotracheal intubation is unsuccessful, a King Airway Device shall be utilized if an advanced airway remains necessary Advanced Airway Management ▪P – Positioning ▪ Position the patient in a semi-recumbent position (approximately 200) or in Reverse Trendelenburg, if possible Advanced Airway Management ▪M – Monitor (& Verify) ▪ “Regardless of the quality of the laryngeal view, or the confidence of the intubator, verification of tracheal placement must be performed on every patient.” ▪ Richard M. Levitan, M.D. Guide to Intubation and Practical Airway Management, 2004 ▪ “Clinical verification, as a sole means of verifying endotracheal tube placement is not uniformly reliable. EMS services performing endotracheal intubation should be issued equipment for confirming proper tube placement.” ▪ NAEMSP Position Paper on Verification of Endotracheal Intubation, July 1999 Advanced Airway Management ▪M – Monitor (& Verify) ▪ Confirming placement must be done: ▪ Using multiple methods ▪ Immediately after placement ▪ After major movement of patient ▪ After manipulation of neck ▪ After giving ET medications ▪ If absent ETCO2 waveform or unexpected ETCO2 detector color change Advanced Airway Management ▪M – Monitor (& Verify) ▪ Clinical Verification ▪ Direct visualization of tube passing cords (orotracheal intubation) ▪ Rise and fall of chest ▪ Absent epigastric sounds ▪ Present breath sounds ▪ Good BVM compliance ▪ Condensation in tube ▪ Tube fogging alone is not a reliable differentiator between tracheal and esophageal intubation Advanced Airway Management ▪M – Monitor (& Verify) ▪ Methods to confirm ET tube placement after clinical verification ▪ Esophageal Intubation Detector Device ▪ ETCO2 measurement - waveform capnography is preferred Advanced Airway Management ▪E – ETCO2 ▪ Pitfalls of colorimetric CO2 detection devices: ▪ Cannot provide a specific CO2 value ▪ May fail if litmus paper gets wet (airway secretions, vomit, etc.) ▪ Subject to expiration (usually 2 years) ▪ Requires six breaths in cardiac arrest patient to get accurate reading Advanced Airway Management ▪E – ETCO2 ▪ Benefits of waveform capnography: ▪ Provides important indicators for overall respiratory function ▪ Airway integrity/proper advanced airway placement ▪ Provides indication of clinical death and return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) ▪ Quantifies the effectiveness of interventions ▪ Assisted ventilations ▪ Hyperventilation Advanced Airway Management ▪E – ETCO2 ▪ Waveform capnography additional notes: ▪ Adjust rate of ventilations based on capnography readings ▪ If ETC02 goes above 45, increase rate of assisted ventilations (no more than 12/minute) ▪ If ETCO2 falls below 35, slow rate of assisted ventilation ▪ ETCO2 should be maintained around 35 in head injured patients Advanced Airway Management ▪Additional Notes ▪ Suspected head/brain Injury guidelines ▪ Consider prophylactic Lidocaine 1.5mg/kg IV/IO for suspected head/brain injury patients ▪ Lidocaine should be administered 3 minutes prior to intubation whenever possible ▪ Sedation ▪ If the patient regains consciousness while the advanced airway is in place, do not remove the advanced airway. Use restraints as necessary and consider sedation with midazolam: ▪ IV/IO – 0.1 mg/kg (max dose 4 mg) ▪ IM/IN – 0.2 mg/kg (max dose 8 mg) Advanced Airway Management ▪Assessing the difficult airway (LEMON) ▪ L – Look externally (short/fat/hairy etc.) ▪ E – Evaluate (3-3-2 Rule) ▪ M – Mallampatti (evaluate on awake patient ahead of time) ▪ O – Obstruction (airway/vomitus/oral trauma) ▪ N – Neck (cervical collar, short fat necks) If each of these categories was given a point, the closer the score is to 5, the higher the likelihood of a difficult airway Advanced Airway Management ▪L - Look Externally ▪Obesity or very small ▪Short muscular neck ▪Prominent Upper Incisors (buck teeth) ▪Receding jaw (dentures) ▪Burns ▪Facial trauma ▪Edema ▪Facial hair Advanced Airway Management ▪E - Evaluate the 3-3-2 Rule ▪3 – Mouth opening: Should open wide enough for 3 fingers to be inserted between upper and lower teeth ▪3 – Mandible length: 3 fingers is normal length (measured from the tip of the chin to the hyoid bone) ▪2 – Distance from the hyoid bone to the thyroid notch: Should be at least 2 fingerbreadths Advanced Airway Management ▪M - Mallampati Classification ▪A method used by anesthesiologists ▪A reliable tool used to predict difficult direct laryngoscopy ▪Best success with intubation is a Class I or II Class I Class II Class III Class IV Advanced Airway Management Mallampati Class II Advanced Airway Management Mallampati Class IV Advanced Airway Management ▪O - Obstruction ▪ Blood ▪ Vomitus ▪ Teeth ▪ Dentures ▪ Tumors ▪ Impaled objects ▪ Peritonsillar abscess ▪ Epiglottis ▪ Edema Advanced Airway Management ▪N - Neck ▪ Spinal precautions ▪ A c-collar can prevent manipulation and movement of the mandible ▪ Utilize a 2nd rescuer to apply manual in-line stabilization and release the collar for the duration of the attempt ▪ Impaled objects ▪ Lack of mobility Advanced Airway Management ▪Importance of First Pass Success ▪ Hypoxia associated with multiple attempts (2833 attempts)1 ▪ First attempt - 4.8% ▪ Second attempt - 33.1% ▪ Third attempt - 62% ▪ Fourth attempt - 85% 1Mort TC. Emergency Tracheal Intubation Anesth Analg. 2004: 99:607-13 Advanced Airway Management ▪Maximizing First Time Success ▪ Pre-oxygenate ▪ Suctioning as necessary ▪ Position the patient – increased head elevation ▪ Utilize Macintosh #4 blade for orotracheal intubation ▪ External laryngeal manipulation (ELM) ▪ Straight-to-cuff ET tube with stylet or tube inducer as indicated Advanced Airway Management ▪External laryngeal manipulation (ELM) ▪ Backwards Upwards Rightwards Pressure (BURP) ▪ A simple technique that may improve laryngeal visualization and facilitate intubation Advanced Airway Management ▪Problem-solving ▪ If ventilation becomes difficult or the patient desaturates after intubation, consider DOPE: ▪ D – Dislodgement ▪ O – Obstruction ▪ P – Pneumothorax ▪ E – Equipment Advanced Airway Management ▪Advanced Airway Placement PEARL #2 ▪ “Do not attempt to re-establish an advanced airway unless you have changed something” ▪ Move location/position ▪ Different advanced airway device ▪ Blade Change ▪ Suctioning ▪ Magill Forceps ▪ ELM/BURP ▪ Flexguide Advanced Airway Management ▪Video Laryngoscopy ▪ Video Laryngoscopy is within the paramedic scope of practice and may be utilized by S-SV EMS approved ALS providers ▪ Due to the many models of devices available and the lack of medical literature recommending one device over another, the decision on which device to utilized rests with the individual provider Advanced Airway Management ▪ET Tube Introducer ▪ Considered first choice by many physicians for difficult airways when epiglottis can be visualized but vocal cords cannot ▪ Patients with suspected c-spine injury in whom epiglottis could be seen had 100% successful intubation within 21-45 seconds use of introducer Advanced Airway Management ▪ET Tube Introducer ▪ In simulated patients with c-spine injuries and Mallampati Class 3, first attempts were more successful with tube introducer than laryngoscope alone ▪ Can be passed through laryngeal opening despite limited visibility ▪ Angled end is directed anterior ▪ Passes more easily than ET tube when supraglottic or laryngeal edema present ▪ Vibrates over tracheal ring in 65-90% of placements Advanced Airway Management ▪ET Tube Introducer Utilization Steps 1. Use standard orotracheal intubation preparation and procedures, including cricoid pressure. 2. When blade optimally exposes all or some of the laryngeal opening, introducer is advanced. Advanced Airway Management ▪ET Tube Introducer Utilization Steps 3. Holding introducer in right hand and the angled tip upward, gently advancing anteriorly (under the epiglottis) to the glottic opening (cords). (It is important to note the orientation of the upturned tip as the introducer is inserted) Advanced Airway Management ▪ET Tube Introducer Utilization Steps 4. If the cords are visualized, direct through the cords. For other situations, direct the introducer under the epiglottis, and feel for a vibrating sensation as the tip ‘washboards’ across the tracheal rings. Advanced Airway Management ▪ET Tube Introducer Utilization Steps 5. For epiglottis only views, the upturned distal tip must be kept midline and immediately underneath the epiglottis. Advanced Airway Management ▪ET Tube Introducer Utilization Steps 6. The length of the device allows it to be advanced until resistance is encountered (at the carina). 7. If no resistance is encountered and the entire length of the introducer is inserted, the device is in the esophagus. Advanced Airway Management ▪ET Tube Introducer Utilization Steps 8. Correct placement is assumed when the device is directed through the cords, the tip is felt vibrating against the trachea, or you meet resistance while advancing (at the carina). Introducer in trachea Advanced Airway Management ▪ET Tube Introducer Utilization Steps 9. Advance until the thick black line is at the lipline. This ensures that enough of the introducer is protruding from the mouth to allow tube passage. Advanced Airway Management ▪ET Tube Introducer Utilization Steps 10.Have the intubator maintain visualization of the of the epiglottis with the laryngoscope while the assistant feeds the tube over the introducer. 11.Remove the introducer, confirm airway patency, and secure the tube. Advanced Airway Management ▪Advanced Airway Placement PEARL #3 ▪ “Even the best can miss, don’t be invested in your airway” ▪ Don’t be afraid to allow another person to intubate ▪ Even the best will have a bad day and not be able to perform the skill ▪ Convincing yourself you placed the tube properly and ignoring clinical signs could lead to a poor patient outcome….Death Advanced Airway Management ▪Critical Thinking and Clinical Decision Making ▪ Must be able to “think outside the box” ▪ Early identification and anticipation of airway management needs is the key to survival ▪ Be proactive vs. reactive