module_acquisition and methodsJune13

advertisement

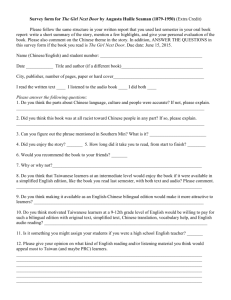

1 Second Language Acquisition and Teaching Methods: Chinese Dr. Meng Yeh Objectives As a result of information learned from this lesson, participants will: 1. understand the major second language acquisition processes and language learning theories 2. apply various language teaching methods to develop effective classroom instruction and activities Standards SBEC: Languages other than English Standards 1.1k, 1.3k, 1.4k, 1.6k, 1.1s, 1.2s, 1.3s, 1.5s, 3.1k, 3.2k, 3.3k, 3.4k, 3.5k, 3.6k, 3.6s, 3.7s 2 Pre-Test 1.How does Cognitive Approach view the process of second language acquisition? a. b. c. d. Language learning is similar to learning to play piano. Humans have a special cognitive faculty for language learning. Learning a L2 is easier for adults because of their cognitive development. Language input process is more critical than language production. 2. What is a Comprehensive Input suggested by Krashen (1982)? a. b. c. d. The input is clearly explained in terms of grammar and function. The input that students can thoroughly understand The input is a little beyond students’ current level of competence The input is provided in a large quantity with visual and contextual clues 3. How can the process of language learning be effective in the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky 1978)? a. b. c. d. Pedagogical planning takes into consideration of various learning styles. The teachers provide an anxiety-free learning environment. Self-learning is emphasized, encouraging students to explore their own learning. Students are offered the opportunity to interact and negotiate meanings. 4. According to the scaffolding method, a teacher should a. design a variety of activities to promote peer-learning b. demonstrate the desired outcome of a task through modeling c. enhance students’ proficiency by using only the target language d. adopt the authentic materials used by the native speakers 5. What is the main principle when designing a cooperative learning activity? a. ensure that each student is accountable for his/her individual contribution b. provide students opportunities to search for relevant information c. evaluate the accuracy of student language output d. encourage the application of communicative strategies as a team 3 Introduction The focus in this module is on guiding the teachers to design effective language instruction with the understanding of research results on second language acquisition (SLA) and teaching methods. Language instructions should be developed to achieve the standards-based curriculum goals and performance-based assessment.1 The recent SLA studies and language methodologies have directly impacted on classroom instructions. The research of SLA intends to answer the question ‘How do people learn a second language?’ Language teaching methods center on ‘How do teachers help students learn a second language?’ Hence, the understanding of SLA and teaching methods can lead the teachers to effectively facilitate the student learning in a classroom setting and design meaningful instructional materials and engaging activities. The first part of the module introduces some major theories and research findings on SLA and discusses the results that shape the current concept of language teaching. The main topics include: Communicative Competence Cognitive Approach Social-cultural Approach Individual Learner Differences The second part of module demonstrates a number of language teaching methods based on the studies of SLA. 1 Task-based Language Teaching Cooperative Learning Approach Using the Target Language Teaching Chinese Sounds Teaching Chinese characters The module of Standards, Curriculum and Assessment: Chinese provides detailed discussion of standards-based curriculum and performance-based assessment. 4 Communicative Competence Language competence, suggested by Chomsky (1965), is the intuitive knowledge of rules of grammar and how the linguistic system of a language operates. In the past three decades, the definition of competence has been expanded to a broader notion of communicative competence. Communicative competence, the ability to function in a target-language community, consists of the following four skills and knowledge (CelceMurcia, Dörnyei & Thurrell, 1995). socialcultural competence: the knowledge of social, cultural and non-verbal contextual knowledge of the language studied linguistic competence: the knowledge of the grammar and forms of the language actional competence: the functional skills to apply linguistic knowledge to a variety of situations strategic competence: a set of skills, verbal or non-verbal, assisting the speaker to be understood in order to maintain communication For instance, your socialcultural competence helps you bring the appropriate gifts, such as fruit, as a guest to a Chinese family in Beijing. You are able to engage in a conversation using correct words and sentence with your linguistic competence. Actional competence helps you apply proper expressions to greet people, give compliments, and thank for the invitation. When you forget certain words or phrases, you can rely on strategic competence to continue the conversation, by using gestures, indirect/alternative ways to express the same things, or know how to ask for assistance. The broad view of communicative competence recognizes that students need more than grammatical and linguistic knowledge to function in a communicative setting. They need to be able to apply the linguistic forms correctly and functionally. They should be familiar with social-cultural factors, so they can speak and behave in culturally appropriate ways. Students should be given ample opportunities to engage in spontaneous conversation in various real-world situations and learn the conversational strategies to avoidcommunication breakdowns. 5 Cognitive Approach Cognitive Approach views second language acquisition (SLA) similar to other kinds of learning. This approach characterizes acquisition of knowledge in terms of input and output. Learning, from the perspective of cognitive psychology, involves processing information input, through constructing the working memory to internalizing the knowledge in the long-term memory, and finally production (using the knowledge) (Eysenck 2001). The studies on language input and output seek to explain how students process the language input and produce the output based on their L2 knowledge. A. Comprehensible Input Krashen’s (1982) hypothesis of comprehensible input initiated the discussion of what kind of input best assisting students to learn a second language. Comprehensible input is an optimal quantity of input that helps student’s acquisition of the language. The input is not defined by grammatical sequence, but should be interesting, understandable and a little beyond their current level of competence (i + 1). “i” is viewed as the current competence of the learner, and “1” represents the next level of competence that is little beyond where the learner is now. The implication for classroom instruction is that the effective input has to be meaningful and purposeful, challenging but not overwhelming. Krashen’s hypothesis has sparkled a great deal of thought and discussion in the profession in regard to the role of input in language learning. For example, Long (1983) suggested three ways that input can be made comprehensible: by modifying the input, using familiar structures and vocabulary by using linguistic and extralinguistic features, such as gesture, prior knowledge by providing the interactional structure of the conversation, i.e., students interacting with each other toward mutual comprehension In the next topic, we will focus on the input processing strategies used by the learner and the modified input that the teacher can provide for their students. B. Processing Input Processing language input, according to Lee and VanPatten (2003), involves connecting grammatical forms with their meanings. Learners use automatic and controlled processing in their comprehension and production of the second language. In automatic process, students do not analyze the linguistic elements, but use them automatically. For example, the response ‘You’re welcome’ to ‘Thank you’ is automatized. In contrast, students activate controlled processing to think consciously how to produce correct sentences. Controlled processing becomes automatic processing when learners practice regularly and what they practice becomes part of the long-term memory. The study done by Lee and VanPatten suggested a set of processing principles used by learners. For example: 6 Learners process content words in the input before anything else. Learners prefer processing lexical items to grammatical items for semantic information. Learners prefer processing more meaningful morphology before less or non-meaningful morphology, for example, simple past regular endings rather than redundant verbal agreement. Lee and VanPatten (2003: 142) defined structured input as ‘input that is manipulated in particular ways to push learners to become dependent on form and structure to get meaning.” The guidelines for developing structured input activities include: present one thing at a time keep meaning in focus move from sentences to connected discourse use both oral and written input have the learners do something with the input keep the learner’s processing strategies in mind For example, in a Chinese class, students are learning the vocabulary of a variety of activities (watch TV, go to a movie, swim, dance, etc.) and the sentence pattern of using frequency adverbs, such as often, rarely, once a while, every week. A structured input activity may require students to do a survey among the classmates. They have to use Chinese to ask the following questions and find out the answers from their fellow classmates. In this activity, students engage in a meaningful survey using new words and patterns to form questions. Find out from your classmates, if they go a movie every week watch TV often go dancing once a while … C. Interlanguage Interlanguage is the language of the learner (Selinker 1974), a system in development and not yet a totally accurate approximation of native speaker language. The characteristics of interlanguage are: interference from the native language overgeneralization of grammatical rules, such as applying the past tense rule to goed strategies involved language learning strategies involved in second language communication, such as circumlocution The following diagram depicts the role of interlanguage in the language input processing (Lee and VanPatten 2003). Structured input becomes intake when the language is 7 comprehended and used by learners to develop a linguistic system (interlanguage) that they then use to produce output in the language. structured input intake interlanguage (developing system) output Ellis (1999) suggested that learners construct interlanguages in the long-term memory to represent what they have processed from the input. An interlanguage consists of a network of form-function mappings rather than grammatical rules. When the learner processes the input and identify the meaning (function) of a specific grammatical feature (form), he/she is mapping a form-function connection. This view stresses that teachers should guide the learners to focus on input and comprehension before production. Interlanguage studies describe the linguistic system developed in the mind of the learner. Since it is a system in development, learners make errors when using the target language. It is a natural part of the learning process. Teachers provide correct input and engage learners in attending to that input, which help learners improve their interlanguage to incorporate new and/or more accurate feature. D. Language Output Krashen (1982) only focused on input for language acquisition. Swain (1985) argued that comprehensible input is not sufficient for students to learn the target language. They need to be provided opportunities to produce output, using the language to communicate and achieve higher language competence. In the process of producing language output, students use the new words and rules, discover the gap between what they want to say and what they are able to say, and reflect what they know about the system of the target language. Ellis (1999) examines the L2 production in terms of fluency and complexity (such as word-order). The result suggests that the learners cannot attend to all aspects of L2 production (i.e., fluency, accuracy, complexity) simultaneously. Thus, it is important that the teachers design a variety of tasks that strengthen different skills of L2. The tasks should also produce the language output that is meaningful, purposeful and motivational. The output from mechanical drills is not beneficial for language acquisition, since there is no communication purpose. Language production acquires more than linguistic knowledge. Students need to learn to use various communication strategies, such as gestures or circumlocution. In communicative type of output activities, students consolidate what they know about and realize what they need to learn. Through repeatedly using the language in communicative situations, students move from analyzing the linguistic rules and develop automatic process. 8 Social-cultural Approach In the social-cultural approach, language acquisition is considered to best occur in a social setting. Learning with others exceeds what the learner is able to do alone. From Vygotsky’s (1978) viewpoint, social interaction is critical for learning and development of one’s language competence. Learners can perform tasks at actual developmental level without any assistance from others. Completing a task at potential development level, learners need assistance from his/her peers or teacher. Through interaction with others, the learner progresses from the ‘actual development’ to ‘potential development.’ In this process, potential development of the learner becomes next actual development. Between the two levels is what Vygotsky called the learner’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), the grey area, as illustrated in the following diagram. actual development potential development scaffolded interaction (assistance, guidance) ZDP LEARNING PROCESS Language learning occurs in ZPD when the learner receives scaffolded assistance from the teacher. In scaffolding, the teacher simplifies a complex task into manageable small steps based on students’ language development. During the scaffolded interaction in the ZPD, the teacher is not the traditional authority figure who provides the solution. Instead, the teacher facilitates the learners’ search for solution, by highlighting relevant features, pointing out the discrepancy between what has been produced and the possible solution, reducing stress and frustration, and modeling appropriate use of the language. The interaction among peers in ZPD also promotes language learning. In a language class, the interaction continues through negotiation of meaning, which are the exchanges between learners as they attempt to resolve communication breakdown and to work toward mutual understanding (Pica 1987). To reach a clear understanding of each other, the two parties must use the language to seek clarification, check comprehension and request confirmation that they have understood or are being understood by others. Collaborative dialoguing (peer-peer dialogue) has positive effect on language learning, in which students in groups or pairs use collective resources to produce the language and construct a solution. Ohta (2001) demonstrated that students were able to produce utterance collaboratively that were beyond them individually. However, students do not always produce error-free utterances working in groups. Thus, to enhance language development in ZPD, on the one hand, students should be encouraged to be active 9 conversational participants who interact and negotiate meaning. On the other hand, there are situations in which assistance and guidance should be provided by the teachers. 10 Individual Learner Differences The differences of each learner influence the degree of success in learning a foreign language. Motivation and anxiety are pertaining to affective factors. A student’s learning style also affects the language development. A. Motivation According to Masgoret and Gardner (2003), motivation is the most influential factor in predicting the success of learning a new language. Motivation involves both the reasons that learners have for learning a language as well as the intensity of their feelings. Two types of motivation are distinguished (Gardner & Lambert, 1972): instrumental: learning a language for a practical reason, such as getting a better job or to fulfilling an academic requirement integrative: learning a language to fit in with people who speak the language natively and to understand the culture associate with that language, for example, heritage learners typically integratively motivated Learning a language is a long-time commitment. To maintain the strong motivation, classroom experience is critical. As Dörnyei (1994) maintained, students tend to retain their motivation when the class content, teaching methods, learning tasks are interesting and engaging. The teacher’s personality, teaching style and relationship to students promote positive feeling about the target language and its speakers. Student motivation is stronger when the learner has specific rather than general goals for language learning. It can be very helpful when teachers guide learners to develop more specific goals for language learning. B. Anxiety A number of studies (see Horwitz, Tallon, & Luo, 2009) suggested that about a third of language students experience some foreign language anxiety. Language classes are typically more public and more personal than classes in other subject matters. The classroom activities, such as speaking in front of a group and interacting with other spontaneously, may cause anxiety. Gregersen and Horwitz (2002) found that anxious learners tend to make more errors and resort to their native language more often. Anxiety can cause learners to skip classes or even withdraw from language study. The traditional classroom structure with the authoritarian teacher-centered atmosphere promotes anxiety. Imagine that your language teacher asked you to share something personal in the target language, and just as you were getting to the important part, he or she interrupted you to correct a grammatical error. It is very important to consider that students who appear unmotivated may be experiencing anxiety. To reduce anxiety, teachers provide interactive group works before asking them to perform individually, encourage students to express anxious feelings, guide them to concentrate on communicative success rather than formal accuracy. In 11 essence, the teacher should help anxious students to focus less on what they are doing wrong and more on what they are doing right. C. Learning Styles a. Multiple Intelligence A learning style is a general approach to process and perceive information that a learner uses to learn. Multiple Intelligences (MI), proposed by Gardner (1993), refer to human intelligences that are capable of learning skills or knowledge in many different ways. For example, Visual-spatial Verbal-linguistic Logical-mathematical Bodily-kinesthetic Musical-rhythmic Interpersonal Intrapersonal Naturalistic The concept of multiple intelligence leads the teachers away from the traditional classroom that treat students as a homogeneous group, with the teacher presenting the same exercises to all students at the same time, and expecting the same answers. MI Theory encourages the teachers to investigate the diversity which exists in every classroom, and to find out more about students' strengths and weaknesses as related to the learning process. Then, the teachers can develop instruction and assessment that address each student’s need and intelligences. b. Language Learning Scarcella & Oxford (1992) have identified the following learning styles when students study a foreign language. analytic-global: sensory preferences: intuitive-sequential: Analytic students are detail-oriented and concentrates on grammatical information. Global students enjoy interactive tasks expressing their ideas and are not disturbed by making errors. Students may have different sensory preferences in learning, such visual, audio and hands-on. Visual students learn better with visualized information. Auditory students enjoy verbal interaction and may have difficulty with written works. Hands-on students like action and movement around the classroom, touching and producing objects. Learners prefer various organizations as how the material is presented. Intuitive students can think in non-liner and 12 random manner, perceiving the big picture. Sequential learners like step-by-step ordered presentation and may have difficulty seeing the bigger picture. orientation to closure: The learners oriented closure ask for grammatical rules and have little tolerance for ambiguity. They may have difficulty participating in open-ended communication. Awareness of students’ preferred learning style helps to explain why some aspects of language learning seem to come easier to certain students and why some students struggle with particular approaches. The teachers should strive for a mixed of instructional methods that match students’ different learning styles. 13 Try this1 (Second Language Acquistion) 1. What kind of input should be provided by the teachers according Lee and VanPatten (2003)? a. authentic materials used by the native speakers b. structured materials integrating forms and meanings c. engaging materials that draw students’ attention d. communicative materials that students can use immediately 2. Which of the following describes the characteristics of “interlanguage”? a. a system built by learners that maps language forms to the meanings b. a language used by the teacher to ensure the learners’ comprehension c. a set of grammatical rules mastered by the learners d. a process that encourages the interaction among the students 3. With the understanding of Gardner’s (1993) concept of Multiple Intelligences (MI) What should the teachers do? a. reduce students’ anxiety by focusing on what they do right b. motivate students through building specific goals c. design open-ended communicative activities d. understand each student’s strengths and weaknesses 14 Task-based Language Teaching Task-based teaching approach has been developed to help students achieve the communicative proficiency. We have learned that mechanical drills and exercises have limited value in contributing to language acquisition and communicative skills. To improve the teaching methods, communicative tasks are designed to provide students interactive opportunities to negotiate meaning, clarify content, and confirm understanding in the target language. A communicative task focuses on guiding the students to perform meaningful tasks using the target language in real-world situations, such as visiting a doctor, conducting an interview, or calling customer service for help. A cycle of activities are usually associated with a task: pre-task: Students are presented what will be expected in the task phase. In pretask phase, teachers model the use of language and practice the key words/patterns that will be used to accomplish the task task: During the task phase, the students perform the task, usually in pairs or small groups. A task may also involve individual students searching and analyzing information. post-task: In the phase of post-task, the students present result of the task to the rest of the class. The teacher and other students provide feedback. Three main principles of the task-based approach will be discussed: focus on form, authentic materials, and scaffolding. The last part will present sample task activities. A. Focus on Form ‘Focus on form’, in the task-based teaching methods, is a methodological principle that emphasizes both linguistic structures and communicative skills. ‘Focus on form’ is different from ‘focus on forms’ which only attends to pre-determined discrete-point grammar. ‘Focus on form’ stresses the importance of designing meaning/functionfocused activity, while guiding students to notice certain linguistic feature in context. (Long 1991). Research has shown that a focus on meaning (communication) alone is insufficient to achieve language proficiency, which needs to be improved upon also by systematic attention to linguistic elements. More importantly, learning certain grammatical structures is to serve the communicative objectives in a unit. For instance, if the task is about narrating a most exciting travel experience, students need to be familiarized with the usage of time expressions indicating the past, past tense of verbs, and adverbial connectors to narrate the event. Pre-task activities can be designed to guide students to pay attention to these linguistic elements which are necessary to accomplish the task. 15 Thus, the objective of a task determines what grammar to be learned to conduct communicative works. B. Authentic Materials The communicative task-based approach emphasizes the use of authentic language and material in instruction. ‘Authentic material’ is the written or oral text produced for the native speakers in that language, such as realias, magazines, newspapers, broadcastings, movies, songs, poems, and so forth. Such language samples reflect a naturalness of form and an appropriateness of cultural and situational context that would be found in the language used by members of the target language. Hence, the use of travel brochures, hotel registration forms, train schedules, product ads, labels, signs will acquaint students more directly with real language than will any set of contrived classroom materials used alone. Authentic materials should be incorporated into instruction at all levels, starting with the beginning students. Authentic material is intended for use by native speakers of the language, not tailored to a specific language curriculum. Thus, teachers should carefully choose the material and design appropriate tasks based on student language proficiency level. Otherwise, the material and tasks may cause anxiety and frustration among students. The key principle is to understand that the difficulty of the authentic material is determined only the by tasks that we ask the learner to carry out based on that material and not on the material itself (Terry 1998). Also, for each task, ample contextual and visual cues are provided to enhance the comprehension. In pre-listening activities, students are guided to concentrate on comprehending the key words and main points. For example, for beginning Chinese students, once they have learned the number 1 to 20, teachers can use the authentic materials, such as supermarket ads or McDonald menu. The task for the students is to find out the price for a variety of item on the ads and menu. C. Scaffolding “Scaffolding’, a concept first suggested by Vygotsky (1978), is a procedure with various methods for the teacher to help the students to learn new materials. Scaffolding is incorporated in the task-based language teaching as a critical process to optimize the impact of a task on student learning a language. Scaffolding does not mean that the teacher simplifies the task, but the goal is to help students accomplish a complex task through small manageable steps. During scaffolding, students receive needed support from the teacher. Such support will be gradually reduced with the learner taking up more responsibility when they are ready. The teacher carefully designs effective verbal and instructional scaffolds that enable students to practice the individual parts of a task within the context of full performance. 16 Thus, the process of learning of students is facilitated through the graduated intervention of the teacher. For instance, for a task that students with proficiency at the novice-high level are asked to describe one’s home and room, the teacher can design the scaffolded help as follows: modeling: to demonstrate the desired outcome, through explaining and questioning to make the critical features of the task explicit The teacher uses ppt slides to describe her house and various rooms. Before the presentation, the teacher goes through a list of five questions with the students. The questions, relevant to the house/room in the presentation, prepare student to listen to the main ideas. student contribution: activate their prior knowledge and review what they have learned, solicit students’ active involvement During and after the modeling, with the ppt visual slides, the teacher consciously lead to students to express what they know by using the language they have learned, such as Is this house big? How many rooms are there? What are there in the front yard? comprehension checks: verifying and clarifying their understanding Based on the presentation, the teacher can use a memory game to ask students to recall what they have seen on the slides. guided practices: design activities in which students have to use the new words/patterns For example, use a survey activity in which students utilize the new vocabulary and sentence patterns to find out Whose house has the most rooms? Who likes to live in a big city? Whose house has a swimming pool? D. Communicative Task Samples In this section, three communicative tasks are described, including interpersonal, interpretive and presentational tasks. a. interpersonal speaking Theme: best friends Students: 10th graders, novice-high Task: Students are divided in pairs and use the following questions in Chinese to find out the information of your partner’s best friend. How and where did you meet? Why is he/she your best friend? What does he/she look like? What is his/her personality? 17 b. Interpersonal Writing Theme: school and community Students: 12th graders, intermediate low Task: Your school is going to host an exchange student from Wuhan, China. The student’s name is Shu Wang. Write him a letter in Chinese welcoming him to your school and your community. In your letter, write about: You town or city: location, size, special feature You school and typical daily activities Your interests and hobbies Two or three things that you expect Shu Wang will fine strange or different, given what you know about Chinese high schools and how they are different from your school. c. presentational speaking Theme: planning an activity Students: 9th graders, novice mid Task: Students are divided in pairs. Each pair is given different situation. Each pair presents spontaneous exchanges in Chinese to act out the given situation. Situation 1 You two are talking what to do for the weekends. Decide a plan on Saturday, including times and activities. Situation 2 You two want to go out for a dinner. Discuss what you want to eat. Each of you recommends a type of food and a restaurant of your favorite. You two need to make a final decision together. 18 Cooperative Learning Approach Cooperative learning is the instructional use of small groups so that students work together to maximize their own and each other’s learning. It is defined as students working together to attain group goals that cannot be obtained by working alone. Cooperative learning approach stresses that students learn more by talking, explaining, arguing, and working together with their classmates than listening to a teacher’s lectures. The benefits of group or pair work include higher retention and achievement, development of interpersonal skills and responsibility as well as heightened self-esteem and creativity (Johnson & Johnson, 2004). In a cooperative learning classroom, the teacher plays the role of a facilitator, not a knowledge transmitter. The students are the center. They take responsibility of active learning through working with the peers and receive consultation from the teacher. When designing a cooperative activity, the following principles are important: Objectives: The teacher needs to ask what students are able to do with the language? in an activity. In other words, what is the activity goal that will be achieved through the language use? Assessment: After each activity, the teacher should find ways to evaluate students’ learning, such as selecting several students to report the results or handing in a written summary. Individual Accountability: Students are assigned specific roles in the task. Each student is accountable for his/her individual contribution and his/her own learning. Each student’s performance is required and evaluated. Group Interdependence: The knowledge or skills of each teammate helps the team accomplish the task. Students need to interact with the content and with fellow students to accomplish the task. Managing groups: It is ideal to have 2-4 students in a group. It is easier for inexperienced teachers to start with paired activities. During the group works, the teacher walks around the classroom to make sure that each group is on task and group members are using the social skills to interact with each other (such as praising others, taking turns to speak, and etc.). Four cooperative learning activities will be introduced here. The activity samples are from the eWorkshop Student-centered language Classroom through Cooperative Learning, produced by Dr. Meng Yeh at Rice University with STARTALK funding. The eWorkshop aims at guiding teachers to be effective in facilitating student-centered learning using engaging and creative cooperative-activities that maximize student interaction and language output. The workshop presents twenty-five cooperativelearning activities, designed by middle school, high school and university instructors in Texas. The activities are presented with detailed activity plans consisting of objectives, proficiency-levels, preparation process, instructions and worksheets. Fifteen activities have classroom video clips which reveal students’ working in groups and completing the 19 task. To see the details of the following activities and other activities, please view http://startalk.umd.edu/teacher-development/workshops/2009/CTCLI/content/. A. Dialogue Building, by Fang Ji, Johnston Middle School, HISD This small-group activity Dialogue Building is designed for 7th graders (novice-mid). Each group will be given a drawing and a set of flash cards. Based on the drawing of the situation given, each group builds a dialogue using the flash cards. The flashcards in yellow are for building sentences, and the card in blue for questions. After building dialogues, group members take turns to practice reading it aloud. B. Have You Been To…?, by Meng Yeh, Rice University Have You Been To…? is a whole-class cooperative activity for the college students in the third-semester Chinese class (intermediate low). The activity is to practice the use of experiential marker guo in Chinese through finding out which students have been to what places. The students are given a worksheet with a list of 10 different places. They go around the classroom to interview their classmates and see who has been to the places listed in the worksheet. C. Recycling, by Elsie Chang, Cinco Ranch High School, Katy ISD The small-group activity, Recycling, is for the high school students in the 4th-year Chinese class (intermediate mid). Recycling starts with a jigsaw reading activity and ends with a roundtable discussion. In this cooperative task, students in each small group help each other comprehend an article related to environment and recycling. Once the main points of the article are clear to everyone, the groups will engage in discussion for the issues raised in the article. Each group will present their views to the class. D. Family Tree, by Yimiao He, Shepton High School, Plano ISD Family Tree is a small-group activity for 9th graders (novice high). The goal of this activity is to read a passage about David’s family and fill out the information correctly in the family tree worksheet. Since each student is given different part of the David’s family information, the students need to communicate with each other to complete the worksheet. 20 Using the Target Language Standards-based curriculum and language teaching places emphasis on using the target language (TL) by the teacher and the students in classrooms. Usually the classroom is the only environment where students are exposed to the language. Using the TL maximizes the comprehensive input for students and students’ language output. Chinese, instead of English, being used in everyday classroom makes the language real for students and sees that Chinese is immediately useful to them. Students learn to respond spontaneously and get used to not understand every word. When the TL is used most of the time in a classroom, it helps bridge the wide gap between carefully controlled secure classroom practice and unpredictable real life language encounters. Teachers can stay in the target language by using a variety of strategies. Use parallel or multiple sources to convey the meaning/message: visuals (ppt, drawings, photos, props, graphs, diagrams, poster, real objects, video clips, etc.), body language, facial expression, intonation, movement, and prior knowledge. Avoid switch in and out of the target language: Arrange the class into the TL block and English-language block (which is for explaining complex grammar/instruction or dealing with discipline problesm). While during the TL block, no English is used and do not translate Chinese into English. Thus, students know that they are only allowed to use Chinese. Tailor the TL input to students’ level: Comprehensive input is the guiding principle. The language used by the teacher can be a bit higher than the students’ level. Classroom routines and useful expressions: Build a repertoire of words and phrases to carry out consistent classroom routines, which help to create a predictable environment that supports language use and strengthens the sense that the target language is simply a part of the environment. The expressions are used frequently daily (possible several times), such as Time for class 上课了, Please say it again 请再说一次。 The expressions apply collectively; this enables an individual student who has not understood to follow by mere imitation, such as Open your books 把书打开. Some expressions do not require the students to respond orally but simply to carry the instructions physically: Please sit down 请坐下。 21 Teaching Chinese Sounds A. Pinyin Teaching Chinese sounds involve two aspects: pinyin and tones. Chinese uses pinyin, the Roman alphabets, to indicate each character’s pronunciation. With respect to the vowels and consonants, Mandarin has fewer sounds than English. However, Mandarin has six consonants do not exist in English, such as zh, ch, sh, r, j, q, x, which pose some challenge for English-speaking students. With comparison to English jeep, cheese, and she, along with the description of tongue position and lip shape, the teachers can guide students to improve their pronunciation. Please see below the comparison and the drawing indicating the place of articulation. Mandarin consonants: zh, ch, sh, r, j, q, x unaspirated affricate zhī 知 aspirated affricate chī 吃 fricative place of articulation post alveolar 齿龈后 tongue manner shī 施 jī 基 qī 七 xī 西 palatal 硬腭 tongue blade touching pre-palatal tongue tip touching the low teeth spread the lips jeep cheese she palatal 硬腭 tongue blade touching palate some rounding of the lips Tongue tip touching the post alveolar area 日 rì (like shì, more vibration): palatal, ride, road, rain ‘zhi’ in Mandarin ‘jeep’ in English ‘ji’ in Mandarin 22 B. Tones Chinese is a tonal language. Mandarin has five tones with various pitch contours. See the chart below. Tones are considered very difficult for non-tonal language speakers, such as English. Many L1 features may cause interferences. For example, English has intonation and stress which frequently interfere with the production of correct tones at the sentence level. 5 tones in Chinese Tone 1 Tone 2 Tone 3 Tone 4 Neutral tone 55/HH 35/MH 214/LH 51/HL 1/L As indicated in the table below, the pitches of Chinese tones range from 1 (the lowest) to 5 (the highest). In contrast, the pitch range in English is narrower, only 2 to 4. Thus, English speakers have difficulty in producing Tone 1 high enough or Tone 4 falling to the lower pitch. Pitch Ranges in Chinese and English (White, 1981) Chinese speaker English speaker pitch range: 1 to 5 pitch range: 2-4 C. Strategies for Teaching Tones and Pronunciation For the beginning students, Yeh (2010) suggested the use of the visual musical staff for individual characters and sentences to reinforce the perception of the pitch contour of each tone. The visual image leads students to be aware of the wide range of Chinese tone pitches. Here is the illustration of five tones and the tones of the words in a sentence. 5_______________________________________________________ 4_______________________________________________________ 3_______________________________________________________ 2_______________________________________________________ 1_______________________________________________________ mā má mǎ mà ma 23 5__________________________________________________ 4__________________________________________________ 3__________________________________________________ 2__________________________________________________ 1__________________________________________________ nǐ jiào shénme míngzi? you call what “What is your name?” name Zhang (2008) used various body movements to highlight the production of the tones. Tone 1: one arm stretching high with your index finger drawing a line in the air Tone 2: both hands (pawn up) rising Tone 3: both hands (pawn down) pushing down Tone 4: moving one arm from high to low and simultaneously stumping one foot Yeh (2010) contented that pronunciation activities should be meaningful, communicative, and engaging. It is no effect of doing mechanic drills on isolated words or sounds. When designing activities to help students practice tones and pronunciation, the teacher should keep in mind: Use multiple-sensory methods: auditory, visual, body movements, rhythm Practice pinyin and tone together in a meaningful way Not drilling on individual sounds and single syllabus out of context Here is an example. The activity guides students to practice the pinyin xie with different tones and meanings. The activity starts with words and places the words in sentences with visuals. Minimal pairs: from words to sentences xiēzi, xiézi xiēzi xiézi 24 Wǒ pà xiēzi. Tā chuān xiézi Teaching Chinese characters Chinese writing system is character-based, not alphabets. Learning writing characters is a challenging task. The difficulty results from two main factors: 1) Each character contains various numbers of strokes and the learners have to remember how each stroke is written; 2) Characters themselves do not represent the pronunciation, so the learners have to remember both the meaning and sound of each character. Chinese characters have been used for the past four thousands years. There are over 50,000 characters in total, but knowing 3,000 characters is sufficient to become literate and to be able to read newspapers. Learning 3,000 characters is still a daunting process. However, many characters share forms and elements. Teachers need to guide the students to perceive the commonalties among the characters. In the following, some strategies of teaching characters will be discussed. A. Understand the Components in Characters Students should learn the shared components among characters. The earliest characters were pictographs, created by drawing a presentation of an object. Most new characters are constructed by using existing character forms (example 1). 90% of the characters are formed by two elements: meaning part and sound part (example 2). The meaning part is also called ‘radical’. Example 1: The meaning of a character is constructed by two pictographs. 木 mù ‘tree’ 休 xiū ‘rest’: combination of the character 木 mù ‘tree’ 人 rén ‘person’ 木 and 人 are two pictographs. and the characters 人 rén ‘person’, indicating a person leaning on a tree to rest 25 Example 2: The characters are formed by meaning and sound parts. Meaning part Sound part 日 rì ‘sun’ 水 shuǐ ‘water’ 氵 心 xīn ‘heart’ 忄 characters 青 qīng ‘green’ 晴 qíng ‘sunny’ 青 清 qīng ‘clear’ 青 情 qíng ‘feeling’ Thus, exercises can be developed to notice the components of characters. Here are two examples from the Workbook Level 1 of The Routledge Course in Modern Mandarin Chinese (Ross, He, Chen and Yeh 2010). Example 3: Group the following characters according to the radical they share, writing each character in the line next to its radical (Workbook, L10, p.182) 不,你,都, 他,呢, 哪, 那, 什, 两,吃, 可,会,吗,们 口 亻 阝 一 Example 4: Group the following characters in terms of a part that they share in common. The shared part need not be the radical in each character. Write the shared part first, and then list the characters that share the part afterwards, as in the example. You can use a character more than once. (Workbook, L12, p. 231) 都, 馆, 什, 怎, 们, 生, 饭, 对, 然, 他, 日 谢, 点,想, 星, 老, 是, 可, 这, 还, 起,只 Shared Part 人 Characters 人,大,太, 天 B. Strokes: Basics and Sequence 26 Students should be familiar with basic strokes (about 20 different strokes) which compose the characters. There is a conventional sequence to write characters, such as from left to right, from top to bottom. Native speakers learn the sequence when they are taught characters. Even though the sequence is arbitrary, the systematic order helps learners memorize the writing of characters. Therefore, at the beginning of learning to write characters, the teacher should take time to introduce the components of each character and the order of the strokes. Character exercises should be given to familiarize students with the basics and sequence of characters. Here are two examples (Workbook, L11, p.205) Example 5 Write the first two strokes of each of the following characters. a. h. 还 家 b. 太 i. 星 Example 6: Complete each character by writing in the missing strokes. a. bàn half b. kàn see, look at, read c. qǐng invite C. Delay Character Writing There are two approaches to character learning. One approach requires students to write the characters that they are able to say from the very beginning. Most currently textbooks adopt this approach. The drawback is that the students are overwhelmed by the burden of both pronunciation and character writing. Moreover, the teacher spends less time on demonstrating the basics of writing characters because of time constraints. Hence, the second approach (Ross, He, Chen and Yeh, 2010) suggests that the beginning class focus on pinyin, tones, speaking and listening. Once the foundation of pronunciation is established, characters can be introduced at a slow pace, starting with 10 characters each lesson and gradually increases the number. In the second approach, students are able to say more than they can write. The texts for them may mix characters with pinyin. This approach ensures that students have thorough grasp of both pronunciation and character writing from the very beginning. Teachers should also provide students the opportunity to type characters. AP Chinese, starting 2007 administered by the College Board, requires students to type the answers for free response items, such as writing an email or describing an event. Typing Chinese characters also helps students’ pinyin spelling and recognition of characters. 27 Try this 2 (Language Teaching Methods) T/F questions 1. Using the target language in a classroom should start with the beginning students. (True) 2. ‘Focus on form’ approaches emphasize both communication and linguistic knowledge. (True) 3. English intonation and stress helps the learning of the tones in Mandarin. (False) 4. Students should be guided to follow the stroke order when writing a character. (True) 5. Authentic materials include the lesson texts in textbooks written for language learners (false). 6. Mandarin has more vowels and consonants than English. (False) 28 Conclusion Studies on second language acquisition have provided valuable insight of the process and challenges of learning a language. Learning a language involves linguistic analysis, cognitive development and social interaction in a community. Each student’s affective factors and learning style also shape the learning experience and achievement. Based on the research results of SLA, language teachers have a better idea how to structure optimal language input and maximize student output to build students’ interlanguage. The current language teaching methods suggest that communicative tasks are most effective to enhance students’ language proficiency. In completing a task, the teachers should incorporate the target language, authentic materials, and scaffolding steps to assist students. The classroom pedagogy is student-centered and includes small-group cooperative activities. Students are encouraged to take responsibility of their own learning and use the language to work with other members in a team to accomplish tasks. The teaching methods can be readily implemented in a Chinese language class. Since tones and characters are two unique aspects of the Chinese language, strategies of teaching tones and characters are suggested in this module. 29 post-test 1.How does Cognitive Approach view the process of second language acquisition? e. f. g. h. Language learning is similar to learning to play piano. Humans have a special cognitive faculty for language learning. Learning a L2 is easier for adults because of their cognitive development. Language input process is more critical than language production. 2. What is a Comprehensive Input suggested by Krashen (1982)? e. f. g. h. The input is clearly explained in terms of grammar and function. The input that students can thoroughly understand The input is a little beyond students’ current level of competence The input is provided in a large quantity with visual and contextual clues 3. How can the process of language learning be effective in the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky 1978)? e. f. g. h. Pedagogical planning takes into consideration of various learning styles. The teachers provide an anxiety-free learning environment. Self-learning is emphasized, encouraging students to explore their own learning. Students are offered the opportunity to interact and negotiate meanings. 4. According to the scaffolding method, a teacher should e. design a variety of activities to promote peer-learning f. demonstrate the desired outcome of a task through modeling g. enhance students’ proficiency by using only the target language h. adopt the authentic materials used by the native speakers 5. What is the main principle when designing a cooperative learning activity? e. ensure that each student is accountable for his/her individual contribution f. provide students opportunities to search for relevant information g. evaluate the accuracy of student language output h. encourage the application of communicative strategies as a team 30 References Celce-Murcia, M., Dörnyei, Z. & Thurrell, S. 1995. Communicative competence: A pedagogically motivated model with content specification. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 6, 5-35. Dörnyei, Z. 1994. Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 78, 273-284. Ellis, R. 1999. Input-based approaches to teaching grammar: a review of classroomoriented research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistic 19, 64-80. Eysenck, M. 2001. Principles of Cognitive Psychology. Hove: Psychology Press Gardner, H. 1993. Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books. Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. 1972. Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. Gregersen. T. and Horwitz, E. K. 2002. Language learning and perfectionism: Anxious and non-anxious language learners' reactions to their own oral performance. The Modern Language Journal 86, 562-570. Horwitz, E. K., M. Tallon & H. Luo (2009). Foreign language anxiety. In J. C. Cassady (ed.), Anxiety in schools: The causes, consequences, and solutions for academic anxieties. New York: Peter Lang. Johnston D. W., & Johnston, R. T. 2004. Assessing students in groups. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Krashen, Stephen D. 1982. Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. New York: Pergamon Press Lee, J. F., & VanPatten, B. 2003. Making communication language teaching happens. San Francoise: McGraw-Hill. Long, M. H. 1983. Native speaker/non-native speaker conversation in the second language classroom. In M. A. Clarke & J. Handscomb (eds.), On TESOL ’82: Pacific perspectives on language learning and teaching, 207-225. Washington, DC: TESOL. Long, M.H. 1991. Focus on form: A design feature in language teaching methodology. In K. DeBot, R. Ginsberg, and C. Kramsch (Eds.), Foreign language research in crosscultural perspective (pp. 39-52). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Masgoret, A. M. and R. C. Gardner. (2003). Attitudes Motivation, and Second Language Learning: A Meta-Analysis of Studies Conducted by Gardner and Associates. Language Learning, 53, 123-163. Nunan, David. 2004. Task-based Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ohta, A. 2001. Second language acquisition processes in the classroom: Learning Japanese. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Pica, T. (1987). Second-language acquisition, social interaction, and the classroom. Applied Linguistics, 8, 3-21. Ross, C., He, B., Chen, P., & Yeh, M. 2010. The Routledge Course in Modern Mandarin Chinese Textbook and Workbook, Level 1. New York: Routledge. Scarcella, R. C & Oxford, R. L. 1992. The tapestry of language learning. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. Selinker, L. 1974. Interlanguage. In J. H. Schumann & N. Stenson (eds.), New Frontiers in second language learning, 114-136. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. 31 Swain, M. 1985. Communicative competence: some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In S. Gass & C. Madden (eds.), Input in Second Language Acquisition, 235-253. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. Terry, R. M. 1998. Authentic tasks and materials for testing in the foreign language classroom. In J. Harper, M. Liverly, & M. William (eds), The coming of age of the profession, 277-290. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. Vygotsky, L. S. 1978. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological process. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. White, C. M. 1981. ‘Tonal Production Errors and Interference from English Intonation,’ Journal of the Chinese Language Teachers Association, V14(2), 27-56. Yeh, M. 2010. ‘Teaching Chinese Sounds,’ one-day Chinese Teacher Workshop in April, Houston, Texas STARTALK program.