November 2008 - Word Version

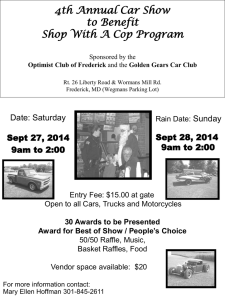

advertisement