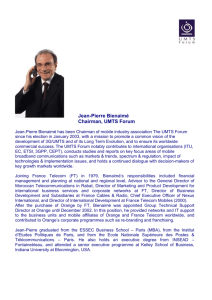

1 A Frenchman's Love Story with America By Daniel Dorian A group

advertisement

217 A Frenchman’s Love Story with America By Daniel Dorian A group of ten French Alps ski resorts known as SNO had chosen Annie Famose as their spokesperson. Annie was a member of the dominating French alpine skiing national team and had won two medals at the 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble as well as three medals, including one gold in slalom, at the 1966 World Championship in Portillo, Chile. She proposed that Air France use American Hot Dog skiers for the promotion of these resorts in the United States. I suggested we make a movie. Hot Dogging was in its infancy then. This form of acrobatic skiing had not yet caught on. The only filmmaker who had produced movies about it was Warren Miller whose company, Warren Miller Entertainment, had specialized in winter sport photography since 1949. Using picturesque French Alps resorts as backdrops for ski stunts would lend our short film a style of its own. Annie brought to the project four American champs from Utah, Colorado, Idaho and Vermont, all of them daredevils, all of them famous among aficionados. They were Scott Brooksbank, Ken Tofferi, Corkey Fowler and Eddie Ferguson. Because of her busy schedule, she asked that we start filming soonest. I had less than a week to find a cameraman specialized in skiing photography. An editor from Ski Magazine strongly recommended that I hire a friend of hers from Vail, Colorado. His name was Bruce Barthel. He was, she assured me, a veteran ski photographer. 218 I called him. He was interested. Could he meet me in Paris in three days? He didn’t have a passport. I intervened with the State Department and helped him get one in forty-eight hours. The shooting schedule was gruesome. We had ten resorts to cover and only ten days to do it. We filmed during the day and travelled at night. Bruce’s ability to ski backwards while photographing Eddie Ferguson freestyling down steep slopes reassured me. He knew how to ski, but did he know how to frame, how to pan, how to zoom, how to light? He seemed to take an awfully long time to load the camera and to prepare his shots. Granted, filming fast moves on white snow with a deep blue sky in the background wasn’t simple. Still, there was something about Bruce’s work habits that troubled me. Video playback did not exist then. A director could not verify on the spot if his cameraman had done a good job or even if he had captured any image at all. I was impatient to see the work of this guy I had gambled on. So, right after we landed in New York, I rushed to DuArt labs to have the material developed ASAP. The photography turned out superb. Some sequences, particularly the ones showing the four Hot Doggers schussing in deep powder, the somersaults, the spread eagles, Eddie’s freestyle, the moguls were breathtaking. Barthel had excelled. Bobby’s editing was equally brilliant. I called my movie French Kick. It had been in the can for a week when a young man from Paramount came to my office to discuss a possible joint promotion. I mentioned, en passant, that I had just returned from the French Alps where I had directed a short on Hot Dog skiing. The man asked if he could see it. I loaded a 16mm projector in one of the back rooms, turned it on 219 and returned to my office, letting him watch the movie by himself. Twenty minutes later, the man knocked at my door. ‘Great stuff! Come to Paramount with me,” he said. “I want to show your piece to my boss. Okay?” We left Air France, walked a few blocks, reached the skyscraper owned by Paramount at ten Columbus Circle, took the elevator to the top floor and entered a spacious office that had a panoramic view of Central Park. An elegant man greeted us. He was Barry Reardon, one of Paramount’s vice presidents. Mr. Reardon, who later became the president of Warner Bros. Domestic Theatrical Distribution, had the reputation in the industry of being “the dean of distribution.” He took us to a preview theater, a few floors below. When the lights came back, he asked, “Is this film available for distribution?” “I suppose it is, Sir.” “Any fee attached to it?” “None. It’s free.” Paramount offered to pay for the blow up of the 16mm into a 35mm version and for the duplication of enough copies for all its theaters in North America. French Kick was tagged to Woody Allen’s Sleeper. Annie Famose and the people at SNO were ecstatic. They could not have possibly expected better exposure. I was curious to see for myself how French Kick was faring with an audience. It was playing in three theaters in town. I went to the one on Third Avenue and Sixty-First Street and sat in the back. The room was packed. The blown-up print looked surprisingly good. The colors were deep and vibrant, the definition unexpectedly adequate. The audience seemed to enjoy my little short. When the narrator summed it up by saying, 220 “Sports Illustrated wrote that the best kept secret is that France has the best skiing, …” the spectators booed and hissed. I was devastated. I only realized weeks later what had happened. De Gaulle had imposed an arms embargo on Israel after the Six-Day War, affirming his support for Egypt, Syria and Jordan. His successor, Georges Pompidou left the embargo in place. In 1974, the year French Kick was released, the newly elected President Giscard d’Estaing met with Yasser Arafat and supported the entrance of the PLO to the United Nations. That didn’t play well with New Yorkers. The hisses and boos had expressed a discontent with France mainly felt in the Big Apple, the largest Jewish community in the world after Tel Aviv. French Kick was well received in the rest of the country. A few months elapsed. I received an invitation to a cocktail party given by Ski Magazine. When she saw me, the editor who had vouched for Bruce Barthel took me aside. “Congratulations! French Kick was terrific,” she said, then paused, looking a bit embarrassed. “But I have to confess. Bruce never handled a movie camera before in his life. He’s a still photographer. French Kick was his first camera job.” OMG! I shivered at the thought of what would have happened if Bruce hadn’t pulled it off. ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ The advent of Concorde spiced my professional life. The French and the British had been working on the design of a supersonic aircraft since the late fifties. Construction of two prototypes began in 1965: 001 built by Aerospatiale in Toulouse and 002 by BAC at Filton, Bristol. In an effort to honor the 221 treaty between France and the UK that led to its creation, they called the airplane Concorde, a word that the French dictionary defines as harmony of feelings or of wills. The English cognate for it is concord, without an e. So, in this battle of egos between two old foes, that little vowel at the end of the name spelled victory for the French. In the UK, the aircraft was initially referred to as Concorde until it was officially changed to Concord by Harold MacMillan, England’s PM, in response to a statement by Charles de Gaulle in which the general dashed Britain’s hopes of joining the Common Market. At the rollout, which took place several months later at Aerospatiale in Toulouse, the British Minister for Technology, Tony Benn, announced that he would change the spelling back to Concorde, thus creating a nationalist uproar. Benn appeased his fellow countrymen by stating that the suffix ‘e’ represented “Excellence, England, Europe and Entente Cordiale.” Yeah, right! In fact, the former Minister received a letter from an irate Scotsman claiming, “You talk about ‘e’ for England, but part of it is made in Scotland”— the nose cone of the aircraft had indeed been built in Scotland. Benn replied, “It was also ‘e’ for Ecosse”—the French name for Scotland—“and I might have added ‘e’ for extravagance and ‘e’ for escalation as well.” What mattered the most to the French is that the e had been reinstated. The country’s honor had been saved. Concorde flew at 1,350 miles per hour, (Mach 2.04), almost twice the speed of sound. A record. It consumed a ton of fuel per passenger on the Paris-New York run, also a record. What a sleek aircraft it was with its double-delta shaped wings and its needlelike droop nose. A French daily compared it proudly to a beautiful white bird. It first linked London to Bahrain and Paris to Rio on January 21, 1976. Later that 222 year, it flew from Paris to Caracas. Congress banned it from landing in the US mainly due to citizen protests over sonic booms. However, following a long public hearing, US Secretary of Transportation William Coleman gave exceptional permission for Concorde service to and from Washington Dulles International Airport for only sixteen months. Flights between the French and the US capitals began on May 24, 1976. Concorde became our number one priority. The plane was new, sexy, way ahead of its time. We had been given a great product to promote. I emphasized the importance of making a movie that would highlight the technical prowess of this new aircraft and flaunt the advantages of supersonic travel. Dick Kuhne, Bob Duffus and myself flew to Washington, where we first filmed the bird being rolled out of its hangar, nose first. Dick chose to shoot that scene lying on the tarmac flat on his back, his camera pointed at the sky, as the aerodynamic nose slowly filled the frame. We took a few standard shots of takeoffs and landings, but Dick and I wanted something more original, more dramatic, a sequence that would illustrate the grace and the power of this incredible machine. We requested the authorization to position ourselves at the end of the runway. Dulles Airport granted it. After a wait that lasted almost half an hour, the Concorde made its grand appearance, slowly turned at the far end of the runway and positioned itself for takeoff, pointing its nose at us, like a prehistoric bird stalking its prey. Then the thunderous noise of its Rolls-Royce/Snecma Olympus 593 engines being revved up pierced the silence of this pristine morning. Concorde, enveloped by the distorting heat waves its powerful reactors had generated, hesitated before rolling toward us majestically. Its roar amplified as it built up speed. Its needle nose dashed straight at us, like an arrow. The moment the 223 aircraft lifted off, almost grazing us, Dick’s body made a fast hundred-eighty-degree turn to catch its belly and to follow it up as it started its climb. The powerful thrust of the engines had flattened us down to the ground. In fact, Dick suffered backaches that lasted a few days, but he got a hell of a shot. After we were done photographing Concorde from all possible angles, we boarded the flight to Paris the following day along with ninety-seven regular passengers. Many people had complained that the seats were too narrow. They were not as spacious or as wide as first class seats, but they were far from being uncomfortable. Others felt claustrophobic in the passenger cabin that was shaped like an oblong tube. I didn’t. It reinforced my impression of having been jettisoned into the twenty-first century. The takeoff was smooth. Once we reached the ocean, the captain announced that he was about to ignite the afterburners. Concorde was not allowed to fly supersonically over land. We definitely felt the acceleration and, for a brief instant, were alarmed by the faint smell of burning that subsided after a few minutes. When the Concorde reached its cruising speed of Mach 2.04, which was confirmed by a speedometer installed at the front of the cabin, everyone applauded. These lucky passengers, who felt privileged to travel at twice the speed of sound, now belonged to a very exclusive club. So did we. As we reached our cruising altitude of fifty thousand feet and as I looked through my narrow porthole, I saw the curvature of the earth below and the dark blue sky above. I couldn’t help but think how different the world had turned out since my childhood, how much progress man had accomplished in forty years. I had been born at a time when some areas in France didn’t even have electricity, when cars constantly broke down, when jets had not been invented, when trains used coal and steam and didn’t run faster 224 than seventy miles an hour. In fact a steam locomotive broke a record on July 3, 1938. It reached the speed of a hundred and twenty-seven miles per hour when it ran down a track that was going slightly downhill. And here I was, about to cross the Atlantic in three hours and twenty minutes! My crew spent this short slice of time capturing images of life on board the first passenger supersonic aircraft in human history: the elegant stewardesses whose uniforms had been designed by Angelo Tarlazzi, the sumptuous meals made of caviar, lobsters and quails accompanied by fine champagnes and vintage wines, the passengers’ faces haloed with the same enchantment children feel when they are being read fairy tales. We were given access to the cockpit where Michel Butel, the captain, reigned. Concorde was a toy that had fallen on his lap at the end of a long career. I will never forget Dick Kuhne filming him in the narrow cockpit, holding his heavy camera at arms length, steady as a rock. Our documentary featured an executive who had taken the Concorde flight to Paris at Dulles Airport and a fashion buyer who had taken the eleven o’clock a.m. Concorde flight to Washington at Charles de Gaulle Airport that same day. She would land at Dulles at eight-twenty in the morning, two hours and forty minutes before she had departed from Paris. We had to secure air-to-air shots. Air France’s public relations department killed two birds with one stone. It organized a short press trip on the Concorde and chartered a Falcon Jet equipped with a telescopic ramp inside of which a camera was installed. Dick flew in the Falcon. I was given a seat behind the Concorde captain. Both pilots were in radio contact. 225 The two aircrafts took off from Charles de Gaulle Airport at the same time from different runways. Once in the air, I could see the Falcon flying parallel to us. At one point I heard its pilot ask ours to do a sixty-degree bank, which is pretty steep for an airplane of that size. The Concorde pilot complied, producing a G-force that was physically felt by me and, I am sure, by the journalists in the passenger cabin. He explained, on camera, that Concorde had the maneuverability of a fighter jet, that it could perform steep bends or dives as effortlessly as an F-15 could. After a few maneuvers that made me queasy, I heard the Falcon pilot ask our captain if he could fly back to Charles de Gaulle Airport and perform a touch-and-go. Our pilot agreed, requested the proper clearance to control tower, started losing altitude, approached the runway, touched it with its wheels, accelerated and climbed back up. The Falcon pilot’s voice came on. “The cameraman says he didn’t get it. Can you do another one?” “Sure,” replied our pilot. “Gear down.” A few seconds elapsed. Then we heard the Falcon pilot state, “Your landing gear isn’t down, Captain.” The Concorde captain turned to his engineer. “The gear isn’t down.” “I know,” the engineer replied without emotion. The captain pushed the command of the landing gear one more time —it was activated electronically. Nothing happened. He then turned to his engineer and said, “Let’s try the back-up.” The engineer nodded. “The gear’s still up,” confirmed the Falcon pilot. I tried to stay cool. A belly landing, I said to myself, would be pretty ugly. I noticed that a journalist, who was standing at doorstep of the cockpit, had witnessed the whole episode. Blood had withdrawn from his face. He was on the edge of hysteria. A steward firmly pulled him away and dragged him back to his seat. Meanwhile, the 226 Concorde pilot who had remained absolutely calm, ordered, “Let’s go manual.” The manual command was a simple lever, a handle if you will, that the pilot had to push down. And so he did, to no avail. He then proceeded to crank that handle up and down, up and down repeatedly. My stomach got really tight. Finally, the Falcon pilot’s triumphant voice exclaimed with some relief, “Gear’s down.” The Concorde landed. As it rolled down the runway, the captain complained, “Goddamn brakes,” constantly repeating, while pumping the brake pedal, “Come on! Come on!” So much for high tech! The aircraft finally slowed down and came to a stop. I was exhausted. ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ Most opponents of the aircraft claimed that it was deafening at takeoff. It was counterargued that the decibel level produced by a New York subway entering a station was higher than that produced by Concorde. These observations didn’t silence the opponents of the SST. The most vocal among them was Carol Berman, a New York Democrat who had been part of the leadership of The Emergency Coalition to Stop the SST. Concorde was flying over her Lawrence home on approach. Starting in May 1977, she fomented a series of protests at Kennedy Airport during which as many as a thousand cars drove along the main airport roadway at peak time, driving at five to ten miles per hour. As soon as the US government lifted the ban on Concorde in February 1977, the Port Authority of New York opposed the federal decision to grant it landing rights and barred it from operating to and from JFK. 227 The development costs of the supersonic had neared two billion dollars. British Airways and Air France had bought each aircraft for forty-six million dollars a piece. A lot was at stake. The French and British governments and their two flagship airlines pulled their resources. British, French, American lawyers, government officials, executives, public relation and advertising specialists were called upon to fight the interdiction in every conceivable way. They called themselves the Concorde Group. Ed sensed that Concorde might present more risks for his career than opportunities. He chose me to represent the company at the Concorde Group meetings and asked me to perform radio and television interviews. He even ordered me to participate in What’s My Line, a popular television panel game show aired on CBS, during which four celebrities tried to determine a contestant’s occupation. Incidentally, they didn’t guess mine. Fighting for the landing rights of the supersonic was challenging, always stimulating. The French accused the US of protectionism. They felt that the US government had conspired against the Concorde to protect the interests of American airlines and by extension the US economy. They refused to admit that the opposition to the SST was a grass-root reaction, born out of the discontent of the people from Queens and Brooklyn who didn’t want the noise to impact their quality of life. They blamed the federal government and dismissed localism as the source of the problem. They could not fathom that average Joes, who lived in communities as small as Rockaway, Ozone Park, Lawrence, Inwood, Canarsie or Long Beach, could unite and create a political body powerful enough to exert pressure on local institutions, such as the Port Authority. If a 228 similar situation had arisen in France, the government would not have let the people living near and around Charles de Gaulle Airport interfere. It would have made a unilateral decision in favor of the aircraft, regardless of the opposition. I don’t think that executives from Air France or French government officials ever believed in the grass-root theory. It was beyond their comprehension and maybe beyond their culture. ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ The US ban preventing Concorde from landing in New York was lifted in February 1977. I had spent long hours fighting against it. What was I going to do now that I had all this free time? A few months later, Air France stopped its operation to Mexico and to the Caribbean. I saw the writing on the wall. I either would die of boredom or Air France would eventually downsize. I had to find another job. I called Jean-Pierre Farkas in Paris. Jean-Pierre had been the youngest news editor in France. He loved the job but grew restless and asked to be sent to New York as a correspondent. That’s when I met him. We became close friends. I liked this no-nonsense, smart, perspicacious and extremely generous guy. His insatiable curiosity and his desire, even his need to share what he had seen, heard or felt with the rest of the world made him a great reporter. He was crestfallen when his outfit, Radio Luxembourg, recalled him to Paris after he had spent two years in New York. He had fallen in love with the city and didn’t want to leave. He confided in me that there were two things he would miss the most, the Sunday New York Times and a good pastrami sandwich. 229 Four years had elapsed when I called him to ask him if he could help me find a job in my former profession. A few days later, he informed me that a large press consortium that included Le Point, one of the two top weekly magazines in France, needed a US correspondent. He said he’d have to see me in person to discuss the matter. I told him I would fly to Paris the following Saturday. We decided to meet at a restaurant a block off the Champs-Elysées. My flight was scheduled to take off at seven in the evening. At four, I walked into Carnegie Deli and ordered one of their legendary oversized pastrami sandwiches that I put in my carry-on, careful not to squeeze it. I landed at Charles de Gaulle at seven-thirty the following morning. I had a few hours to kill before my meeting. I called my friend Yanou Collart who owned a sublime apartment at 1, Rue François 1er, a few blocks from the Champs-Elysées and asked her if she’d let me take a shower at her place. Yanou was a successful publicist whose main clients were the top French chefs then. They were Paul Bocuse, Roger Vérgé, the brothers Trois-Gros and Gaston Lenôtre. She had often taken them to New York where she had orchestrated PR events on their behalf. Yanou was a hard worker, always on the go, always busy planning and organizing unforgettable dinners and events. She became Rock Hudson’s spokesperson when the actor announced to the world that he had contracted AIDS. She also helped New York Magazine food critic Gael Greene launch her Meals on Wheels, the charity that provides home-delivered meals service to people in need. She gave more than she received. I enjoyed her company. She was chirpy, alert, never boring, constantly in search of new ideas. And she was extremely 230 attractive. She was totally consumed by her professional activities, never talked about her private life. Only her close friends knew of her affair with French movie star Lino Ventura. It was close to nine when I arrived at her apartment. She was still in her nightgown. She greeted me with open arms as always and led me to her bathroom. I took a shower, spotted a cozy bathrobe and grabbed it when the entrance bell rang. Yanou yelled, “Do you mind, Daniel?” I stepped into the hallway, crossed to the door and opened it. Lino Ventura was standing there, his muscular body framed by the doorway, daggers in his eyes. It wasn’t difficult to guess what went through his mind when he saw this stranger wearing his bathrobe in his lover’s apartment that early in the morning. Realizing that she had made a terrible faux pas, Yanou came rushing, jumped into Lino’s arms, gave him a prolonged kiss, and trying to sound as detached and spontaneous as she could, casually said, “Oh, this is my friend Daniel from Air France.” She had just saved my life. I arrived at the restaurant Jean-Pierre had chosen forty-five minutes ahead of time, clean-shaven and wearing fresh clothes. I located the maître d’, explained to him that I had just landed in Paris from New York to meet an old friend who longed for a good pastrami sandwich, retrieved the sandwich from my attaché case, gave it to him and went back to the table reserved for us. I was pleased to see Jean-Pierre again. We reminisced about the old times, looked at the menu and ordered elaborate dishes. The place was packed with uptight executives. We ate our appetizers and were waiting for the main courses. The waiter appeared, 231 holding above his head a tray loaded with two large dishes topped by elegant silver dish covers. He lay the tray on a stand, picked the first dish and placed it in front of me ceremoniously, grabbed the second dish and placed it in front of Jean-Pierre with equal decorum. He then crossed back to me, grabbed the dish cover by its handle, lifted it and took a step back, seeking my approbation. Once I nodded, he laid my dish cover on the tray, crossed to Jean-Pierre who had ordered pike quenelles à l’armoricaine and lifted his, uncovering the pastrami sandwich in its Jewish splendor. Here, in the middle of a royal plate, was this humongous pile of fat caught in between two slices of rye bread, framed by two branches of thyme that the chef had artistically placed for visual effect. Once Jean-Pierre recovered from a violent fit of laughter, he grabbed the first half of the sandwich and devoured it. The prospective job didn’t pan out, but I can’t say I had flown to Paris and back for nothing. The look on my friend’s face had been worth the trip. ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ My relationship with my boss had worsened, making my life at Air France unbearable. I had to do something about it. I had reinvented myself so often, but this time had no idea what to do, no inkling, no lead, no new passion, had nowhere to go. I felt trapped. With two kids and a wife to support, I couldn’t take the risk of losing my income. 232 233 XXXI – Maria & le Divorce We always deceive ourselves twice about the people we love — first to their advantage, then to their disadvantage. ~Albert Camus My fallouts with Ed increased in frequency. Spending most of my days idle or doing things I didn’t enjoy doing anymore raised my anxiety level through the roof. The burden of providing for my family with a salary that barely allowed me to make ends meet made matters worse. I became irritable, self-absorbed, worried about the future. It became imperative that I put my potential to better use, and in so doing that I hike my standard of living. I turned to my wife for relief and asked her to get a job, not only to help pay the bills but also to allow me to find an occupation that would better suit my talents and my aspirations. She turned me down flat, arguing that her main responsibilities were to raise our children. She had a nineteenth-century perception of marriage and nothing, not even financial distress, would alter it. She loved the life of a stay-at-home mom. Her mother had done it before her and so had her mother’s mother. That’s the way she had been raised. I am not sure she totally grasped how desperate I had become. I would be disingenuous to pretend that her reluctance to go to work was the sole reason that led me to dissolve my marriage. There was also my encounter with Maria. Maria was a young Chinese-American woman twelve years younger than I. When I first met her in 1967, she was working as a receptionist at Magno, a post-production facility I used for my work. She was eighteen-years old. 234 Magno’s owner, Ralph, had hired her for her good looks. The man appreciated pretty women and aimed at impressing his clients with a stunner. And Maria was indeed of exceptional beauty. Endowed with a sleek body, dark slanting eyes, a perfectly proportioned face and lush jade hair that fell to her waist, she could easily have been a top model if she had been taller. I had always admired her beauty but the thought of making a pass at her never entered my mind. When I first met her I was happily married. Things changed eight years later. It happened in the course of a lengthy telephone conversation during which I launched an implicit charm offensive, not a frontal one. I had glazed my each and every word, including the most trivial, with layers upon layers of veiled desire. You can coat a veneer of sensuality on just about anything. No need to talk about love or love-related subjects to be flirtatious. The fact that we prolonged our camouflaged heart-to-heart for more than an hour, chatting about anything and everything, had a voluptuous subtext. “She is beautiful,” wrote Shakespeare, “and therefore to be woo’d. She is woman, therefore to be won.” I wasn’t the only man enraptured by her looks and alas, not the only one to covet her, but I had an edge over her many suitors. In her eyes no other men came close to being as romantic as the French. My lilt helped tilt the balance in my favor. The day after our telephone conversation, she was mine. Our relationship might not have endured if it hadn’t been for the power of chemistry. Ha, the power of chemistry! Every time he makes love to a woman, a man always runs the risk of being trapped by infatuation, this unreasoned passion so difficult to shake. There are no detox clinics for it. I got hooked on Maria. Our obsession with each other blinded us to reality and made me forget my responsibilities. I had a wife I still loved, was the father of two adorable 235 children, yet here I was, cavorting. I devoted more and more time to Maria, spent weekends with her in upstate New York or in Bucks County, escapades I could not have had without lying. Living a life of lies became increasingly unbearable. I was trapped between passion and duty. Thankfully, my wife put a temporary end to my torment when she saw me with Maria at a time when I was supposed to be elsewhere. This unexpected turn of events precipitated an outcome I had avoided for too long. It forced me to make the cruel choice, to stay with my family or move to Maria’s. I still cared for Annick and I adored my children. Lost in the foggy no man’s land of indecision, I split my time between my home and Maria’s for several weeks. For too long, I had been reluctant to admit to myself that Annick and I were not made for each other. Our incompatibilities were deep, our differences concerning our children’s education unbridgeable, our conflicting views concerning ambition, material success and social mobility irreconcilable. She was comfortable and happy with the status quo, I wasn’t. I never was and I never would. More things divided us than kept us together. I finally decided to move in with Maria. My tryst with her might have hastened the process, but I would have eventually left my wife. I handled the breakup poorly and caused great pain to the children and to Annick, who must have felt so helpless, so devastated by circumstances she could not control. No apology could possibly make up for my actions. True friends refrained from criticizing. All others, including Annick’s family members, saw me as a selfish, irresponsible philanderer. How could I blame them? I had indeed been callous and insensitive. The only thing I could say in me defense is that my 236 thirty-five-year union with Maria would eventually lend credence to the fact that I had the makings of a faithful husband, given the right woman. They saw Maria as a home wrecker, a Chinese whore, but her generosity of the heart and her unconditional love for my children would eventually redeem her in the eyes of many who had condemned her. I was not about to abandon my children but I didn’t want them to experience the grinding existence my parents had put me through. I knew that the separation would cause them to suffer and that it would affect my relationship with them, but I was also convinced that submitting them to the stress and anxieties of divided parents would be more damaging to them in the long run. ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ A few days after I told my wife I had made the final decision to separate, she informed me that she was moving back to France with the children. Nothing kept her in New York anymore. I was responsible for that separation, yet felt bereft, sad to see Annick go, devastated to lose my children. I drove the three of them to JFK on July 3, 1976 and bid them goodbye. When they walked through the departure gate on their way to the aircraft, I felt a chill, yet we were in the middle of summer. The following day was a Sunday. Sixteen tall vessels had sailed to New York to participate in the Parade of Ships that would celebrate the two hundredth anniversary of the adoption of the United States Declaration of Independence. A jubilant crowd had 237 gathered along the Hudson River to watch the pageantry. The city was festive. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky when I woke up that morning. The temperature had reached an ideal eighty degrees. Lying on me bed, I started musing on the happy moments I had spent with my children in the pool in Wilton and suddenly felt an irresistible urge to swim. Yes, it became imperative that I find a swimming pool ASAP. Someone close to Maria had friends who lived in Bronxville in a luxury building that featured one. The avenue where these people were supposed to live, north of Washington Bridge, was lined up with fifteen-story buildings, all fancy, all identical. We parked in front of one of them and started our search. We checked the directories but could not find our friend’s friends. On this gorgeous hot day of July, the plush swimming pools of upscale Bronxville were deserted. Its residents had probably flown to the Hamptons or were watching the ‘Tall Ships’ along the Hudson. The place had the appearance of a ghost town. We felt as if we had been beamed into a lifeless planet, void of joy and laughter, a cold city of glass and cement, the modern version of Pluto’s underworld where swimming pools had replaced the Styx. Was I going to die while staring at my own reflection in a pool, as Narcissus, the character in Greek mythology had? Maria hurt to see me hurt. She suggested I trespass. I put on my trunks in the car and headed toward the pool that belonged to the building in front of which we had parked. The moment I hit the chlorinated water, I identified with Ned Merrill, the seemingly successful and popular middle-aged executive played by Burt Lancaster and featured in Frank Perry’s The Swimmer, a movie released in 1968. Pools were his 238 inexorable conduits to awareness and despair. His intent was to reach home by swimming across friends’ swimming pools that formed a consecutive chain leading back to his house. After he finally reached his destination, after he shoved open a rusted gate, walked through an overgrown garden with an unkept tennis court and knocked on the front door of a locked, dark and thoroughly empty house, we, the audience realized that Ned Merrill had deluded himself. His family had left him a long time ago. Like Ned, I had foolishly hoped that the warm water of a swimming pool would fill a vacuum, heal my sorrow and lead me to a gentle and familiar place. Instead, I realized as he finally did, that I had lost my family. Like him, I suddenly felt emotionally and affectionately destitute. The guilt I had pushed aside during these past months had not vanished. It had only compounded in me. Once I let my guard down, it flooded my soul and left me with a nervous breakdown that paralyzed me for several weeks. The first relief came when my wife allowed the children to come visit me. She had made arrangements for them to sleep at one of her friends’ apartment located two floors below mine. She did not want them to stay with Maria and me out of principle. I went to JFK to fetch them. I dropped them at the apartment where they were supposed to stay and I asked them to come see me as soon as they were settled. Ten minutes later, the bell rang. I crossed to the door, opened it. The look of them broke my heart. Here they stood, side by side, torn, reluctant and at the same time eager to come in. Cécile was eleven and Stéphane seven. They hesitated, debating within themselves whether they should or should not cross the forbidden threshold and finally stepped in timidly. They sat on the edge of the couch and stared at me like miserable puppies. 239 Stéphane was sucking his thumb with a vengeance. I broke the long, uncomfortable silence. “Stéph, Céc, I have something to say and I want you to listen. I am your father and this apartment is your home. This is where you belong, not downstairs, but here with me. So, when in New York, you stay with me. If you don’t want to stay with me, then don’t bother coming. Clear?” “Yes, Dad,” they managed to whisper in unison. They stood up, walked to the front door, their backs slightly bent as if they had been carrying the world’s burden on their shoulders and left. Shortly thereafter, the bell rang. I opened the door and there they were, holding their suitcases, a smile on their faces. ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ The first time I visited them near Paris a few months later, they were alone in their mother’s apartment. Annick had purposely left. I couldn’t wait to take them in my arms. I rang the bell with great expectation. They opened the door, let me in, and before I could hug them, asked me politely but firmly, almost businesslike, to follow them to their room. It was located at the end of a long hallway. Once we got in, Cécile closed the door behind her. Being the elder, she took the lead, looked at me defiantly and calmly stated, “We think you behaved like a bastard and we’re mad at you.” I staggered under the blow. “Why did you leave Mommy?” I took a deep breath, sat in between them and tried to explain why people sometimes decide to go their separate way. I used simple words and made sure not to blame their mother for what had happened. And that was that. We never had similar 240 conversations again, but I realized that the separation had caused damage in their hearts. ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ A few months after Annick’s departure, Maria woke me up in the middle of the night. “I can’t breathe,” she complained. She got off the bed, crossed to her closet and started grabbing some clothes. “What are you doing?” I asked. “I’m getting dressed.” “But it’s three o’clock in the morning!” I gently led her back to bed. She eventually fell back to sleep. She had been stricken by a severe bout of anxiety. That episode would repeat itself every night for several months. ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ To bury our demons, Maria and I drowned ourselves in a life of debauchery. Two gay friends of ours had invited us to spend the summer weekends in their Cherry Grove house on Fire Island. Cherry Grove, commonly called the Grove, was the haven of New York’s LGBTs (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender), a Sodom and Gomorrah where men and women abandoned themselves to the pleasures of the flesh unabashedly. Only a couple of hours from Manhattan, it evoked Rabelais’ Abbey of Thélème, a place ruled by a single dictum, ‘Fais ce qu’il te plaît’ (do as you please); a spot where “all their lives,” according to its 241 sixteenth century French author, “was spent not following laws, statutes or rules, but according to their own free will and pleasure. In all their rule and strictest tie of their order there was but this one clause to be observed, Do What Thou Wilt.” Well, Cherry Grove was indeed an Abbey of Thelème of sorts, with a sexual twist. No cars were allowed on that barrier island, thirty miles long and a quarter to half a mile wide. Narrow and picturesque wooden walks serviced it vertically and horizontally. Our friends’ house sat on top of dunes, on the Atlantic side. It featured an elevated deck that overlooked the pool, the ocean and the sky, lending that part of the property the feel of being an ocean liner. Down below, the wide beach extended to the left and right as far as the eyes could see. It was the ideal playground for sybarites. After a couple of weekends, Maria and I fell into the humdrum of excesses and gratification. I had met Philippe when he was affiliated with the French Broadcasting during my foreign correspondent years. His lover, Tony, was partner in a small advertising agency. They were staunch partygoers and like most successful gays, were surrounded by an eclectic crowd made of artists, executives and intellectuals. One of their best friends was Emilio de Olivares. Like us, he spent his weekends at their house. You would never have guessed that this flaming homosexual was the number two at the United Nations. In New York, he was the Executive Assistant to Secretary General Javier Perez de Cuellar, but in Cherry Grove he was a slut loaded with charm. The moment we’d enter Philippe’s house, we were given joints and the choice of coke or mescaline. We’d have cocktails at the Monster late afternoon and dance all night at the Ice Palace, the Fire Island version of Steve Rubell’s Studio 54 in Manhattan. 242 The Ice Palace was typical of the seventies, a psychedelic disco with its loud music and its flashing lights. What gave it its uniqueness was its crowd of horny queens bursting with testosterone. They had enough energy to jump, twist, and wiggle ‘til the wee hours of the morning. The Ice Palace was their aphrodisiac, an anteroom where they engaged in foreplay before sex. It also displayed the most gorgeous transvestites I ever saw. The eroticism the famous disco exuded never failed to turn me on. ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ I asked a young woman who was a journalist for the French magazine Le Point to spend a weekend with us. Her name was Ghislaine. Philippe’s house was spacious enough to accommodate all of us, including Emilio and Tony’s nephew, a stunning young man. Stiff martinis accompanied by the habitual joints jumpstarted our Friday evening. Tony had cooked spicy sausages, fried onions, peppers and potatoes. Pot had opened up our appetites. We gobbled the Italian-American treat and ended our copious meal with a delicious cheesecake. Then Philippe passed around a tray filled with mescaline pills. We indulged, including the journalist from Paris who was already stoned beyond belief. The hallucinogen boosted our libidos like oil on fire. Not even joints succeeded in curbing our energy and our sexual appetites. Maria and I left the dining room, hurried to our quarters and made love with a fervor we had never experienced before. When we were satiated, we walked to the Ice Palace, danced to our hearts’ content, went back to the house, made love again and rejoined the Palace. We kept doing this back and forth until six the following morning. 243 Later on, we were told that Ghislaine had gone to bed with Tony’s nephew. After making love to her, the young man had switched to Emilio. Then both men had joined Tony and Philippe and had ended the night at the Meat Rack, a parcel of wild land made of sand and low vegetation tucked between Cherry Grove and the Pines, where gays reveled in group sex. One evening, an incident put a sudden end to our intemperance. Maria fell ill after smoking a joint and was stricken by a severe anxiety attack. Her painful illness had reappeared, more devastating than ever. ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ Her attacks had turned more dreadful as weeks went by. Almost a year passed before her symptoms started to subside. It happened in Antibes. Eliane and Jean-Pierre Laffont had invited us to spend a week at their house in south of France. Ginny, the wife of Time Magazine photographer Dirck Halstead, was also their guest. During the first three days of our stay, Maria behaved like a zombie, remaining prostrated, haggard, lifeless for hours, her eyes emptied of the slightest sign of life. She had stopped eating for months and weighed eighty pounds. She also had refused to take her medication. The sight of her was hard on us. Eliane was about to ask me to take her back to New York. On the fourth day, as we were strolling down a narrow street in Antibes, Ginny Halstead turned to Maria and said, with all the tenderness she could muster, “Have no fear. If you faint, we’ll catch you. If you don’t want to talk to us, it’s okay. If you don’t 244 want to eat, don’t. If you don’t want to see us, stay by yourself. But there’s one thing you must know, we love you.” That same day, Maria regained some appetite. At the end of the week, we left Antibes and drove back to Paris. We stopped at Vichy and decided to overnight in the French capital of spas. In the evening, a violent storm accompanied by downpours, strong winds, thunder and lightening rattled the town. When we woke up the following morning the sun was shining, the sky was blue. Maria’s symptoms had vanished. They had passed like the storm. She was her own self again. She had regained her appetite. The nightmare was behind us. The both of us were at last poised to start a normal and healthier life. On May 27, 1986, a French judge granted Annick and me a divorce. 245 XXXII – A Lesson in Humility (Trade #6) Anyone who has never made a mistake has never tried anything new. ~Albert Einstein I would never have left Air France if it hadn’t been for Maria’s support, for Jean-Pierre and Eliane Laffont’s endorsement and for my recklessness. Eliane was a petite woman, blonde, skinny and attractive. She had met Jean-Pierre in high school in Casablanca. After she graduated, she went to study in Paris. One day, an Alfa Romeo hit her as she was crossing an avenue, just outside of her school, near Parc Monceau. The driver, who happened to be Jean-Pierre, rushed out of his car to make sure she was okay. She was shaken but unhurt. Jean-Pierre did not recognize her. He drove her to a pastry shop on the Champs-Elysées in the hope that she’d forgive him for his lapse of attention and maybe, to make a pass at her, killing two birds with one stone. Eliane preferred being well dressed to being well fed. The money she had left after she had paid the rent went toward designer clothes. She was looking great outside but boy, did she starve inside. When the waiter approached her table carrying a large tray filled with goodies, she could not resist. “Which would you like?” he asked. “One of each,” she replied in a flash. She cleaned up her plate, left it spotless, as if it had just come out of the dishwasher. 246 A few days later, Jean-Pierre sent her a large can of apricot preserves accompanied by a note that read, “In case you’re still starving…” He then called her for a date. They spent the evening together. He took her to his place. They fell in love. Jean-Pierre was an aspiring photographer, Eliane an adventuress. She had spent a year with three other ballsy young women driving the fifteen thousand miles that separated Tierra del Fuego, an archipelago off the southern tip of the South American mainland, to Alaska. In 1966, she rejoined Jean-Pierre in New York. They never parted from that moment on. Both of them would eventually take photojournalism by storm. A year later, I introduced Jean-Pierre to Jean Desaunois, who at that time headed Reporters Associés, a photo agency that specialized in showbiz, feature stories and news. It mostly catered to large circulation magazines. Desaunois had been close to the Shah of Iran when he was posted in Teheran as a correspondent. His easy access to the “King of Kings” had earned him and Reporters Associés a lot of money. To reward him, its founder, Loda de Vaysse, promoted him to manager. I do not recall the circumstances in which I met Desaumois. All I know is that I offered him our services. He accepted, happy to land two correspondents in the US. I penned the articles. Jean-Pierre took the pictures. Our first two reportages covered Gilbert Becaud in Chinatown and Mireille Mathieu’s first trip to the United States. She was the new French diva who sounded like Edith Piaf. Jour de France, a popular French magazine, published both items. My collaboration with Reporters Associés didn’t last long—Desaunois was inept 247 at selling copy—but Jean-Pierre kept on working with them until 1968 when he joined Gamma, which was then the top French photo news agency. I had jumpstarted the career of one of the most gifted photojournalists of his generation. Jean-Pierre’s old schoolmate, Hubert Henrotte, gave him his first break. Henrotte had been a photographer for Le Figaro, the French daily, before co-founding Gamma in 1967. In 1968, a reportage that Jean-Pierre had executed for Reporters Associés caught his attention. It covered a chain gang picking cotton in Texas, shackled together with balls and chains, a scene totally anachronistic. Impressed by the quality of the work, Hubert asked Jean-Pierre to be his correspondent in the United States. The following year, he asked Eliane to be Gamma’s rep. She was too independent to work under anyone. She turned him down. Instead, she and Jean-Pierre founded a company of their own that expanded Gamma’s reach considerably. In 1973, Henrotte abruptly dissolved his partnership and with Eliane and JeanPierre, created a new agency he named Sygma, taking with him most of the photographers who were affiliated with Gamma. The Laffonts immediately renamed their New York operation Sygma-USA and upgraded it to a powerful news bureau that not only held its own but that would also equal and in the later years even surpass the revenues of Sygma-Paris. In 1977, Eliane was offered the job of Photo Editor for Look Magazine. She grabbed it following a violent altercation she had with Henrotte the preceding weekend, and left Sygma. Hubert entrusted the management of his US operation to Alain Nogues, one of his top photographers, who after five months decided to leave to resume his career as a photojournalist. A young and inexperienced woman took over and after a year drove 248 the company to the ground. Someone with the competence to rescue it from bankruptcy had to be found urgently. This happened at a time when I desperately needed to branch out into a new activity. I would have done anything to leave Air France. I offered my candidacy to Eliane. She knew I had been the correspondent of Europe #1 and therefore felt that I possessed the journalistic competence to assume this responsibility. She recommended me to Hubert. I flew to Paris to meet the man. When I came face to face with him, he was already a legend among his peers. He was intimidating, had the corpulence, the square and chiseled face of a Gaul, was whole, inside and out. His eyes telegraphed alternatively defiance, irony, mistrust and stubbornness. He could also drown you in tenderness if he liked you and he only liked you if he respected you or if his agency had done well by you. Hubert was intransigent, harsh and paranoid. He always suspected that someone, anyone, was about to take advantage of him. He was pathologically competitive and had a high opinion of himself. Few, in his eyes, measured up to him. He was constantly focusing on problems and complications that sometimes did not even exist. In fact, he would have died of boredom if his professional life had not been strewn with crisis and issues. He admitted to me that he was at his best when confronted with challenges, and photo agencies were awash with challenges. They called him the Citizen Kane of photojournalism. He was not the type of man to ponder or to analyze. He relied on his instincts. He was impulsive, quick at making decisions; he never beat around the bush, never hesitated to give journalists, photographers and employees alike a piece of his mind and, in so doing, made quite a few enemies. His passion for photography, his unflinching tenacity, 249 his indefatigable drive and a flair for stories that were worth telling and selling made him an icon. He knew that photos told these stories more graphically, more powerfully and more emotionally than any other medium. He also was aware of the importance of anticipating news events or at least of catching them in the bud. Magazines and newspapers paid good money to be the first to publish images of a coup, a war, an assassination, a revolution or a natural catastrophe. Three French agencies, Sygma, Gamma and Sipa, dominated the market between 1970 and 1980. Paris had become the world capital of news photography and Henrotte one of its high priests. ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ During my first meeting with him, he could not have been more charming. He trusted Eliane’s opinion and was relieved to have found a candidate who might put his New York subsidiary back on its feet. He offered me a one-year contract that guaranteed me a salary and a ten percent commission on the additional income Sygma would realize each month over the earnings made during the same period the year before. For instance, if the October 1979 revenues exceeded the ones realized in October 1978 by, let’s say, one hundred thousand dollars, I would get ten thousand dollars. I did well by that deal. I wouldn’t have if I hadn’t managed to rescue the company from bankruptcy. It was decided that I would take my functions on October 1, 1979, at the beginning of Pope John Paul II’s pilgrimage to the United States. 250 The company occupied a loft on the seventh floor of an old building located on Fifty-Seventh Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenue. My office was spacious, well lit, furnished with a large desk and with one of these cozy reclining chairs on wheels that made you feel in charge. The first order of my first day was to organize the coverage of the papal visit. Henrotte had flown from Paris to give me his support and to see for himself if I could handle the pressure. Eliane was also on hand. Hubert was pleased when I suggested we post a photographer on the top floor of the building facing St Patrick’s Cathedral. A diving shot of the cathedral and its parvis filled with New Yorkers surrounding the pope would stand out. Eliane suggested that I give Time priority. I called the photo editor who handled international news. Her name was Julia Richer. I introduced myself and told her what we had planned and how many photographers we had assigned. Would she be interested to buy our photos in exclusivity? She would. I suggested a price. She made a counter offer. We met in the middle. “Not bad,” said Hubert “not bad at all.” The honeymoon did not last long. Immediately after I had breathed a sigh of relief, Hubert added, “You should have asked for more. Photographers have to make a living, you know.” Had Julia tried to take advantage of the rookie that I was? I picked up the phone and redialed. As soon as she answered, I firmly said, “The deal’s off. I’m new in this business. I didn’t know what I was doing. I won’t go below…” The tigress must have been taken aback by my temerity. She had the reputation, I was told later, of being ‘difficult.’ She first expressed her outrage, paused and finally said, 251 “Okay. I’ll make an exception for you.” She had compromised because she didn’t want anyone else to buy our photos. That’s the way these magazines operated. They would buy photos not necessarily to publish them but to make sure that they wouldn’t fall into the hands of the competition. Besides, if one of our photographers had been the first to capture an attempt on the pope’s life, for instance, and if his photos had been published in Newsweek, Time’s main competitor, Julia would have been pilloried by her boss. She hadn’t given me a break. She had covered her ass. Meanwhile, Hubert was all smiles. I felt as if I had won a battle…but the war? ÷÷÷÷÷÷÷÷ I had made my first mistake. I had gone back on my word, and my word in that business had to be as good as a signed contract. No contracts were signed when making deals with photo editors, no matter how much money was involved. All we had to do was to agree on a price verbally. We possessed the photos they needed. We had a pretty good idea of what we could get, they knew how much they were prepared to pay for them. There was very little wiggle room for negotiation, it seemed. Well, things were not that simple. Photo editors had their agendas, we had ours, and ours could sometimes be way far apart from theirs. Besides, trying to put a price tag on a photo or on an entire reportage was a subjective exercise, often driven by pure emotion. So many things had to be factored in, even the most unquantifiable ones. What were the circumstances in which a photographer had worked? How many obstacles did he have to surmount to get the story? Photojournalists who covered the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan had to travel to Pakistan, 252 cross the Khyber Pass, ride stinking goat and chicken-filled buses for several grueling weeks and once in Kabul, were forced to hide in taxis to shoot Soviet tanks on the sly, taking the risk of being captured by Russian or pro-government forces, even putting their lives on the line. Photos of Salvador’s civil war taken in a country where very little value was put on human life and where photographers like Olivier Rebot, Christian Poveda or John Hoagland paid the ultimate price for their courage and professionalism should have been priceless. But they weren’t. There was always a limit to what magazines were willing to pay. Of course, the reputation of a photographer had a direct bearing on the dollar value of his work. Eddie Adams, Henri Bureau or Simonpietri didn’t come cheap. If the photos were exclusive, I’d up the antes and even ask the magazines to bid. A scoop could bring a decent amount of money. Selling photos to magazines was pretty much like playing poker. It was a psychological game. To be able to deal from a position of strength, I had to know whom I was dealing with, my clients’ needs and quirks, who were their pet photographers, what the competition had or didn’t have, if the buyer had already bought material that covered the same event from other agencies. Did they need the material for publication or were they just trying to deny the competition an edge? It was also crucial to secure assignments for photographers. Being sent on assignment to Iraq, Afghanistan, India, Indonesia or Togo with all expenses paid beat going there on spec. It gave photographers self-confidence and greater motivation. In those days, magazines would assign ten stories a week, even when they only used three. To get editors to assign photographers to big events required salesmanship and good journalistic reflexes. Being informed every minute of every day and night was a 253 prerequisite. We could not afford to let an hour elapse without checking AFP or AP news wires or without listening constantly to 1010 WINS or to WCBS, the only stations that broadcasted news all day, all night in the seventies. Both were constantly heard in my office as background sound. Even a few minutes of inattention would give a competitor enough time to be the first to ask Newsweek and Time to send his photographers to the West Bank or any other hot spot. After nine years spent at Air France, my reflexes were rusty but not dead. A couple of days before Christmas, the first thing I did, when I stepped in my office early in the morning was to check the wires. A news item from AP caught my attention. The Soviet Union had just invaded Afghanistan. I immediately called Arnold Drapkin, Time Magazine photo editor. He assigned one of my photographers without hesitation. Then I called Jim Kinney from Newsweek. He also assigned another photojournalist from Sygma. We had been the first agency to react to the invasion and were given assignments by the two most influential US magazines way before the competition. Eliane expanded the market when she took over after me, but during my tenure Time, Newsweek and to some extent, US News & World Report, were my number one clients. If a photo made their cover, its commercial value would increase ten, twenty times. It would also be marketable many years hence as archival material. Even being published inside the magazine offered financial rewards and hiked a photographer’s stature. It was therefore essential that I establish good personal relationships with the photo editors of these publications.