פרשת תצוה ושבת זכור The opening of our Parsha deals with Bigdei K

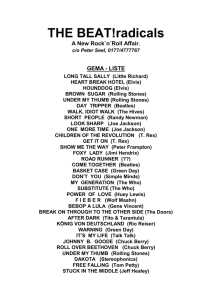

advertisement

פרשת תצוה ושבת זכור The opening of our Parsha deals with Bigdei K’huna. Perhaps, most famous of all of them is the Choshen Mishpat, adorned with the twelve different stones, each one representing a different Shevet. When a question was addressed to the Ribbono Shel ‘Olam, the answer was signaled through the stones as they shone in some sort of sequence that needed to be interpreted. Thus, when the Torah (Sh’mos 28/29) writes: “v’nasa Aharon es sh’mos B’nei Yisroel...al lebo...l’zikaron lifnei Hashem tamid” we understand the message. We know that the heart is the appropriate place for this Choshen Mishpat and that the symbolism and connection between the lev and the memory-for the best!-is obvious However there are two more stones, avnei shoham, that the Torah had previously mentioned (28/9). The name that is given to these stones is quite similar to that of the 12 stones of the Choshen Mishpat. “Avnei zikaron livnei Yisrael”(28/12). They are Stones of Remembrance. The Posuk concludes with what appears to be a repetition: “al sh’tei chseifav l’zikaron”. The stones are on his (the Kohen Gadol) shoulders for a remembrance. It would seem that the characteristic of remembering was already mentioned in the Posuk and that there would be no need to indicate it again. Additionally, the location of the stones, “al shtei chseifav”, appears to be irrelevant to their role as avnei zikaron, and not at all similar to the “heart” of Aharon which would bear the 12 stones, as above. Why, then, was the Remembrance factor repeated again in this context? Remembrance infers the creation of a bond between that (or whom) which is remembered and he who remembers. Remembering means that there is a relationship. How is that relationship formed? Why should one remember something, some event or someone? The psychological issues of memory do not form our question. We want to understand why someone wants to remember. In Parshos Bamidbar and Naso, the Torah tells us how the ‘avoda of transporting the Mishkan and its contents was parceled out among the various families in Shevet Levi. We are told in Naso about the distribution of the wagons that would be used for the movement of the various articles. There it is noted that the family of K’has did not receive a wagon, since “Bakosef Yis’a’u”: they carried the Aron Hakodesh and the Klei Kodesh on their shoulders. It would appear that it is unimportant for us to know that the Aron HaKodesh was hoisted upon their shoulders. In fact, Chazal derived a Halacha from this Posuk and, additionally, give us insight into the work of the Family of K’has. The Halacha, in this week’s Daf Hayomi(Shabbos 92), is that M’leches Hotza’a, carrying from R’shus HaYachid to R’shus HaRabbim, is forbidden also when the object is carried on the shoulder-since such was the actions of B’nei K’has-bakasef yi’sa’u. Besides the above Halacha, the gemara in Er’chin 11 a says the word “yi’sa’u” is superfluous. “If (an article) is on the shoulder, don’t I know that they are carrying? Rather, Yi’sa’u implies shira, song. As the Posuk (T’hillim 81) states S’u zimra(Raise -2- the song)” The implication of this d’rasha is clear. We may read of the hard work of the L’vi’im and sense the burden, the effort, the strain and the heaviness of responsibility. In fact, it was quite the opposite. They enjoyed their work. A song of happiness was on their lift. Yisa’u-they were not overloaded with their charge; they, themselves, were uplifted. What caused this phenomenon? We know that Aron nosei es nos’av. Aron HaKodesh carried those who (appeared to) carried it. Shem MiShmuel in the very beginning of Parshas T’ruma writes convincingly that this nes was not limited to the Aron alone, but applied to all of the carrying and transporting that was done. How could the wagons carry the heavy boards and poles in the Midbar, he asks. Thus, he concludes no movement would have been possible were it not for the nes. If this is so, then all who worked in this field were particularly cognizant of Hashem’s bounty. In their everyday proceedings there were light objects and heavy ones. In their regular activities, some undertakings were physically taxing and others, not so hard. Thus the surprise of the Aron, three cases, gold and wood. And the k’ruvim were on the aron and making it an extremely huge vessel. And they carried it, or so it seemed. Rather when the Aron was lifted up on to their shoulders they felt the Yad Hashem which made this physically impossible task easily doable. It is not extraordinary then that their voices spontaneously opened with songs of praise to Him, Yisborach, who did all this for them. Of course, it would be quite simple to do away completely with the affectations of carrying. Meshech Chochmah notes this in Parshas T’ruma when he questions the very need for the badim, the poles for carrying the Aron Hakodesh, and the Torah’s prohibition of “lo yasuru mimenu”, the badim must remain permanently attached to the Aron. One possible answer to this question is that by being involved with the activity in the way that would be normal, were the burden to be normal, one is reminded of the uniqueness of the event. By assuming the posture of one who carries, by personal preparation for such action and then to have the need for such action nullified, emphasizes that something special is occurring. And, in order for this singular occurrence to remain so, each and every time the motions of carrying must be made so that each and every time the remarkableness is preserved. If we take this principle and apply it to the avnei shoham we have a better understanding of what the Kohein Gadol is to feel and think, and to the kavana he should have during his ‘Avodas HaMikdash. Two massive (each one covered an entire shoulder) precious stones were worn by him. When he donned the garment he certainly felt their heaviness. And now he had them upon him as if they were a burden. But, if he lets them, the burden, as it were, is transferred to Hashem as he enters into a relationship with HaKodosh Boruch Hu and as he enters B’nei Yisroel, as their representative, into a relationship with HaKodosh Boruch Hu. That relationship will be cemented with the Zikaron that these stones enable. We have a right to expect that Zikaron to exist when we have our relationship with Him at the forefront of our thoughts; when we are ever-conscious that He remembers and that from that Remembrance there can be deliverance. -3The L’vi’im were to carry the Klei HaKodesh on their shoulders. They would relate to it as a burden on the one hand and would be aware that it was not they who were accomplishing the task on the other hand. The tool to allow permanent awareness of the miracle they were experiencing was given to them. [If we understand this point, the issue of the death of ‘Uzza, bringing the Aron HaKodesh to Y’rushalayim in the time of Dovid HaMelech can be more easily understood.] However, it is not enough for us to know that Hashem has such ability. We must have a special appreciation for that trait. That is one context in which we may understand and appreciate Shabbas Zachor. Seemingly, our responsibility towards ‘Amalek is laden with a contradiction. In Parshas Ki Teze we are commanded “Mocho Timche”, You are to destroy, whereas in Parshas B’shalach the Posuk writes “Mocho Emche”, I(Hashem) will destroy. This paradox is eliminated very easily. Of course, only Hashem can do anything. All of our activities, in and of themselves, have no value. However, we go through the motions, we are commanded to go through the motions, so that ultimately we will appreciate that which He does. If I sit back and He acts alone, I may get used to His unique Helping Hand. However, if I go through my everyday activities, if I exert myself and then remember that it is He who saves me, my appreciation is far, far greater. Zachor, remember ‘Amalek, we are commanded, so that we will come to destroy them. When we are involved in such activity, then we have the capacity to be fully aware that He and only He saves us.(That is the reason for Ta’anis Esther. The fast discussed in Megilla took place in Nissan, when the lots were cast. We fast in Adar, on the anniversary of the battle since, as the Rishonim state, we can assume when the Jews of Shushan went to war they fasted and did T’shuva in full recognition of the fact that only “Hashem Yilachem Lachem”.) Like all that we ever learn and find relevant to any period of time, we are reminded that there are no coincidences in Limmud Torah or in the Mussar Haskeil that we derive. There are no coincidences since emes is a fact. That is something we must remember, too.