Case Management - Curry International Tuberculosis Center

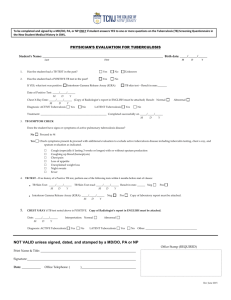

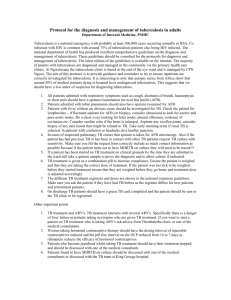

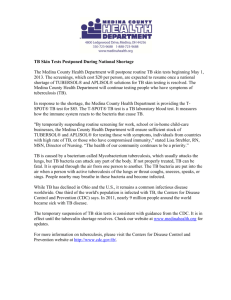

advertisement