Icon - Cadair Home

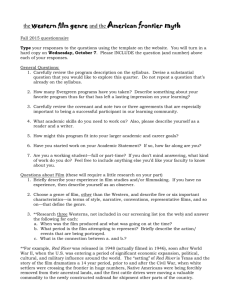

advertisement