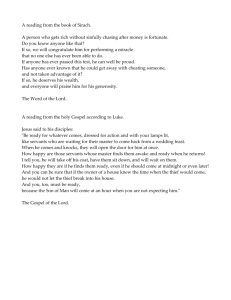

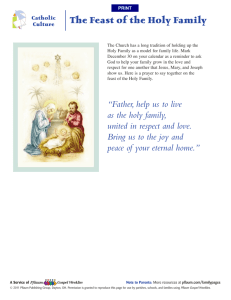

Liturgics

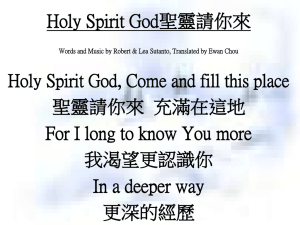

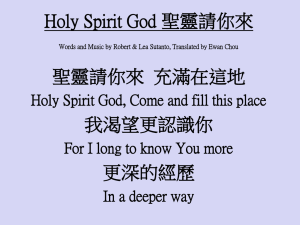

advertisement