Word - Department of Art History

advertisement

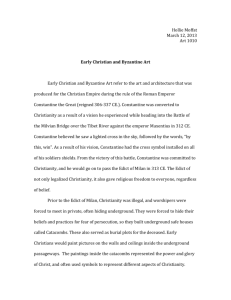

Art History 310: Early Christian and Byzantine Art and Architecture (Spring 2013) Prof. Thomas Dale, Conrad A. Elvehjem Building, Room 203 Office Hours: Wednesdays, 10:00 a.m. – 12:-00p.m. or at other times by appointment Telephone: 263-5783; E-mail: tedale@.wisc.edu Course Description: This course surveys the art and architecture of the Mediterranean world from the rise of Christianity within the Roman Empire in the 2nd and 3rd centuries to the fall of the Byzantine empire to the Turks in 1453. It is an exciting period which sees the formation of a distinctly Christian art and architecture drawing upon the religious traditions of Judaism and pagan Rome on one hand, and that of imperial rulership on the other. The most significant innovations of the period are the invention of the parchment codex–the ancestor of the modern book–the creation of vast domed spaces for worship on an unprecedented scale, and the innovation of a distinctive portrait form still prevalent in the religious culture of Russia and much of Europe: the icon. We will focus first on the city of Rome (between second and fourth centuries) and then turn to the Byzantine or East Roman Empire centered at Constantinople. Amongst the high points of the course are the catacombs of Rome, the mosaics of Ravenna, the architecture of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, the mosaics and Pala d’Oro of Saint Mark’s in Venice. Particular emphasis will be placed on the theory and function of icons or holy images, the use of art to project imperial ideology, the relationship between written texts and pictorial narrative, the relationship between art/architecture and ritual, and the appropriation of Byzantine forms and iconography for ideological purposes outside the empire–especially in Italy and the Russia—and the hybrid culture of the court in Byzantium itself and the middle East. Course Goals: Like the art of other cultures, Early Christian and Byzantine art constitute a pictorial language or “iconography” designed to convey their society’s essential beliefs–religious, social and political. The primary aim of this course is to help you comprehend that language, to understand its changing forms and functions and the power that it exercised upon the beholder at the time it was created. Exams will test you not only on your ability to identify works of art and architecture but also to analyze them in terms of their meaning and appropriate functional contexts. Assignments are formulated to reinforce the tools of iconographical analysis introduced in class and to help you read more critically. Requirements and Evaluation The required texts will provide you with useful background and sources of illustrations for the images discussed in class. In order to succeed in this course, you must attend lectures regularly and take detailed notes: you cannot rely upon web-sites and textbooks because I will present the material in ways that depart from the standard texts. The final grade will be based on participation (10%), a midterm (25%), a final exam (25%) and two short written assignments (40%). Those students who are interested in substituting a single, longer research paper for the two shorter assignments should consult the instructor at the beginning of the semester. The quizzes, which will last no more than ten minutes, are designed primarily to help you acquire a strong visual knowledge of the material in the course. You will be required to identify each work of art in terms of subject matter (or name of a building), location (place of origin), date, patron/commissioner, and medium. You should also be able to jot down a few points pertaining to the meaning and function of the 1 work. The midterm will take up an entire class period and will cover all of the lectures up to and including the week before the midterm date. In addition to short answer identifications, you will be asked to compare and contrast works of architecture, and two write brief essays relating to themes of lectures and the content of assigned readings. Exam make-ups. You must take exams at the time specified on the syllabus. A postponement of the exam will be granted only in the case of serious illness or the death of a member of your immediate family (I will contact the Dean’s office for verification). Under no circumstances will you be allowed to take an exam before the specified time. Required Texts (available for purchase at the University Book Store, State Street) John Lowden, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture (London: Phaidon, 1998). Thomas Mathews, The Clash of the Gods: A Reinterpretation of Early Christian Art, revised ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999. Recommended Texts (available for purchase at University Book Store) Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994). Richard Krautheimer & Slobodan uri, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture, revised ed. (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1989). Cyril Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 312-1453, reprint ed. (Toronto, 1986) For historical and intellectual background to the period covered in the course, you may also wish to read Cyril Mango, Byzantium. The Empire of New Rome (New York, 1980); Judith Herrin, The Formation of Christendom (Princeton, 1987); Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom, Oxford/Cambridge MA, 1996; Peter Brown, The World of Late Antiquity (London, 1989). Illustrations A web-site will facilitate your study of the visual examples discussed in class and to provide a core of images that you will be responsible for in examinations. It can be accessed through the Art History Department Home-Page via Wisc-World or directly at http://www.arthistory.wisc.edu/ah310/index.html You will also find all the essential images in the required textbooks and readings listed under each lecture topic below. In addition, I will post my PowerPoint presentations on Learn@UW. Readings Readings provide essential background to the lectures and points of departure for discussion. You will also be expected to draw upon the content of the readings to answer essay questions in your exams. Most of those readings not in the required texts, marked * in the syllabus, are available in the Course Reader, which can be purchased at Bob’s Copy Shop nearby at 616 University Ave, just a couple of blocks east from the Elvehjem Building. Some materials, marked KL, will only be available in books on reserve at the Kohler Art History Library Reserve Desk. If you need to make a photocopy, please take care not to damage the book. Additional materials may be provided on Learn@UW. Calendar Jan. 22, 24 Introduction I. Why Images? Pagan, Jewish and Christian Art in the Roman Empire between the 1st and 3rd Centuries Engraved Gem with IXΘΥC (Ichtheus = fish), Syria/Asia Minor, late 3rd century (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia) 2 Magical Amulet with Crucifixion of Christ, hematite (bloodstone), Syria, late 2nd to 3rd century (British Museum, London) Priscilla Catacomb, Rome, frescoes ca. 200-250 Sarcophagus from Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome, ca. 250 Endymion Sarcophagus, 2nd century (New York, Metropolitan Museum) Podgoritza bowl, blown glass, Montenegro, 4th century (State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg) Mithraeum, Dura Europos, Syria (now Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven): Cult niche with gypsum reliefs of Mithras slaying the bull, 168 & 170-71 A.D.; painted decoration with deeds of Mithras, ca. 250. Baptistry, The Christian Building, Dura Europos, Syria (now in Yale University Museum), architecture and frescoes ca. 254 Synagogue, Dura Europos, frescoes, ca. 200-230 Terms: sarcophagus; commendatio animae; orant; catacomb; loculus(i); cubiculum(a); arcasolium; refrigerium; dies natalis; domus ecclesiae; John 10 (The Good Shepherd) Readings: KL: Lowden, 4-32; KL: Davis-Weyer, Early Medieval Art, 3-7; * Robin Jensen, Face to Face: Portraits o fthe Divine in Early Christianity (Minneapolis, 2005), ch. IIII: 69-99 “The Invisible God and the Visible Image.” Jas Elsner, “Cultural Resistance and the Visual Image: The Case of Dura Europos,” Classical Philology 95, no. 3 (2001), 269-304. (http://www.jstor.org/stable/1215434) Discussion: Why are figural images problematic for Judaism and Christianity, and to what extent can opposition of figural representation be traced within pre-Christian Roman religion ? Why did Christianity abandon its initial opposition to images? What common features are displayed in the figural decoration of the synagogue, Christian baptistery and pagan temple of Mithras at Dura Europos? What explains the emergence of extensive narrative cycles in the synagogue, and how, according to Elsner, did Judaism definie itself in relation to both Roman and Christian religion through art? Jan. 29 II. The Emperor Constantine and the Conversion of Rome in the 4th Century Portrait of Constantine the Great as Sun-god, Capitoline Museum, Rome Arch of Constantine, Rome, 312-15: marble bas reliefs Cathedral of Saint John Lateran (=San Giovanni in Laterano), Rome, 312/13-18 Basilica of Old Saint Peter's, begun, ca. 319/22 Mausoleum of Santa Costanza, Rome, ca 350, with mosaics Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, from transept of Old Saint Peter's, 359 (now in the Museum of the Grottoes of Saint Peter’s), 359 Missorium of Theodosius, silver, (Academia de la Historia, Madrid) 388 Diptych of the Nicomachi and the Symmachi. ivory (left: N: Musée Cluny, Paris; right: Victoria and Albert Museum, London), ca. 380-390 Terms: Sol invictus; Battle of the Milvian Bridge, 312; Edict of Milan, 313; basilica; nave; apse; fastigium; martyrium; transept; burial “ad sanctos”; Ecclesia ex circumcisione (synagogue); Ecclesia ex gentibus (church of the gentiles); typological/christological interpretation 3 Readings: KL: Lowden, 32-60; Davis-Weyer, Early Medieval Art, 11-15; *Iohannes Deckers, “Constantine the Great and Early Christian Art,” Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art, ed. Jeffrey Spier (New Haven: 2007), 87-109. January 31 III. Sacred Space and Papal Ideology in Fifth-Century Rome Santa Pudenziana, apse mosaic, ca. 400 Santa Sabina, Rome, church, mosaics with personifications of Church and Synagogue, 422-33; wooden doors with Peter and Paul Crowning Ecclesia Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome, wall mosaics of nave and triumphal arch, 432-40 Old Saint Peter's, Rome, original wall paintings ca. 375-400 Readings: Grabar, "The Assimilation of Contemporary Imagery," in Christian Iconography, 31-54; Krautheimer/Ćurčić, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture, 39-67, 167-74; Mathews, Clash of the Gods, II. 23-53; IV.92-114 Discussion How does Mathews call into question the traditional concept of Early Christian art as formulated by Krautheimer and Grabar? How might Matthew’s view about the relationship with “imperial” Roman art be modulated by Deckers’ reading? Feb. 5 IV. Art, Architecture and Civic Ritual in Constantinople, the “New Rome” Column of Constantine (Cemberlitas= “Burnt Column”) Coin of Constantine as Helios, 337 "Tetrarchs", porphyry, originally from the Philadelphion in Constantinople (now on exterior of San Marco, Venice), ca. 300 Hippodrome (including Obelisk of Thutmosis II, 1504-1490 BC, with base set up in 390 AD by Theodosius I; Bronze serpent column, 479BC?) Hagia Sophia II, 405-415 Landwalls of Constantinople, built by Theodosius II, 405-13 Readings: *R. Krautheimer, Three Christian Capitals (Berkeley, 1983), 41-67. *Sarah Bassett, “The antiquities in the Hippodrome of Constantinople.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers v. 45 (1991), 87-96. 4 Feb. 7, 12 (Feb. 12 Meet in Kohler Library to Look at Facsimiles) V. From Roll to Codex: Text and Image in Byzantine and Late Antique Manuscript Illumination in the 5th and 6th Centuries Vatican Vergil (Rome, Vatican Library, MS lat. 3225), ca. 400-25: 45v Aeneas and Achates approach the Sibyl; 73v: Trojan Council; 40r: Death of Dido Quedlinburg Itala (Berlin, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, MS theol. lat. fol. 485 Vienna Genesis (Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, MS theol. gr. 31), 6th century Vienna Dioscurides (Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, MS med. gr. 1), 512, made for Princess Anicia Juliana Rossano Gospels (Rossanno Cathedral Library) Rabbula Gospels, 585 (Florence, Laurentian Library, cod. Plutarch I, 56) Readings: Lowden, 84-96; *Kurt Weitzmann, “Narration in Early Christendom,” American Journal of Archaeology 61 (1957):83-91; Herbert L. Kessler, “The Word Made Flesh in Early Decorated Bibles,” in Picturing the Bible, 141-68. Additional illustrations: K. Weitzmann, Late Antique and Early Christian Book Illumination (New York, 1977)). Discussion: What, according to Weitzmann, is the significance of the shift from roll to codex in the early centuries of the common era? What does he see as the changing relationship between text and image? What conventions of pictorial narrative does Weitzmann single out as clues to a lost archetype? What aspects of Weitzmann’s theory are challenged by Lowden? How does he see the relationship between monumental images and manuscript illumination in a different way? To what extent does early Christian book illustration draw upon Jewish tradition? Feb 14 On-line Lecture (Topic VI. No class today) Feb. 19 Discussion VI. Baptism, Burial and the Afterlife: The Architecture and Mosaics of Ravenna from Galla Placidia to Theodoric Oratory of Santa Croce, Santi Nazaro e Celso = "Mausoleum of Galla Placidia", wall mosaics, ca. 425-50 Baptistery of the Cathedral (Orthodox Baptistery): architecture ca 400-50; mosaics, 458 Arian Baptistery, mosaics ca. 500 S. Apollinare Nuovo, architecture, ca. 490; mosaics, 490-500 and 550 Readings: Lowden, 103-116; Davis-Weyer, Early Medieval Art, 49-53; *Annabel Wharton, “Ritual and Reconstructed Meaning: The Neonian Baptistery in Ravenna,” Art Bulletin 69 (1987), 358-75. Discussion: How do the architecture and mosaics of Ravenna reinforce the rituals of baptism and burial? What are the principles that determine the layout of the pictorial programs of the mosaics? How does Wharton find meaning in the specific arrangement of themes in the Orthodox Baptistery? How does Matthews call into question previous interpretations of processional images in the Ravenna mosaics in terms of imperial 5 ritual? (Compare his approach to that of Wharton). 6 Feb. 21 VII. Early Monastic Art and Architecture in Coptic Egypt Kellia “The Cells”, cells of hermits in Nitrian desert, Egypt, ca. 385-90, 5th-7th ; wall paintings with crosses White Monastery of Shenoute, near Sohag, ca. 450 Monastery of Apa Jeremias, Saqqara, ca. 550; portrait paintings of monastic saints from cell A, 6th-7th centuries Monastery of Apa Apollo, Bawit, remains ca. 5th-6th centuries; paintings 6th-7th centuries: Christ in Majesty with Theotokos and apostles Red Monastery near Sohag, 525-50; with mural paintings of Virgin and Child; saints Readings: Krautheimer/Ćurčić, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture, 110-117 *Elizabeth S. Bolman “Depicting the kingdom of heaven: paintings and monastic practice in early Byzantine Egypt” Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300-700. Ed. Roger S. BAGNALL. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.(2007) 408-433 KL: Elizabeth Bolman, “The White Monastery Federation and the Angelic Life,” in Byzantium and Islam. Age of Transition, 7th – 9th century ed. Helen C. Evans & Brandie Ratliff (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012), 75-77 Feb. 26, 28 VIII. Art, Architecture and Imperial Ritual in Constantinople during the Reign of Justinian ***Feb. 28: Assignment 1 Due (Annotated Bibliography & Outline of Research paper)*** Hagia Sophia III (Church of Holy Wisdom, “The Great Church”), designed by Anthemios of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus, 532-37 Ambo (pulpit) from Beyazit Basilica (now in the Garden of Hagia Sophia) Hagia Eirene, begun 532 Hagios Polyeuktos, built for Anicia Juliana, ca. 524-27 (architectural fragments now in the Archaeological Museum, Istanbul; “pilastri acritani” now displayed outside the south facade of San Marco in Venice) Saints Sergios and Bakchos (known in Turkish as Kucuk Aya Sophia or “Little Hagia Sophia”), built by Justinian as chapel in the Palace of Hormisdas ca. 527-36 Readings: C. Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 312-1453. rpt. Toronto, 1986, 72-102; Krautheimer/uri, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture, 205-37; *Bissera Pentcheva, “Hagia Sophia and Multisensory Aesthetics,” Gesta 50, no.2 (2011), 93-111. Discussion: Paul the Silentiary and Procopius have both left (poetic) literary descriptions or “ekphrases” of Hagia Sophia. How do their accounts relate to the actual building? What do they each emphasize? How is the architecture of Hagia Sophia revolutionary in terms of its planning and spatial organisation? How, according to Krautheimer, does the building serve the ritual of the Byzantine church as well as the imperial entourage? March 5 7 IX. Justinianic Art in Ravenna: Ritual and Politics San Vitale, Ravenna: architecture, built for Bishops Ecclesius and Victor with funding from Julianus Argentarius ca. 530-45; mosaics made for bishops Victor and Maximianus, ca. 540-48 Sant’ Apollinare in Classe, architecture and apse mosaic: 532/6-49 Ivory Cathedra (Throne) of Maximian, ca 550 (Museo Arcivescovile, Ravenna) Readings: Lowden, 116-144; Mathews, The Clash of the Gods , 142-176; *C. Barber, “The imperial panels at San Vitale: a reconsideration,” Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 14 (1990), 19-42; *I. AndreescuTreadgold and Warren Treadgold, “Procopius and the Imperial Panels of S. Vitale,” Art Bulletin LXXIX (1997), 708-723. Discussion: How does the architecture of San Vitale relate to that of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople? What discrepancies in the planning may be attributed to the different liturgical usage in Ravenna? The mosaics of Justinian and Theodora are often viewed as deliberate statements of imperial authority imposed upon the local population in support of Archbishop Maximian (cf. Lowden) and further that the apse mosaic represents a kind of parallel to imperial images of subjects making offerings to the emperor. How does Charles Barber use gender theory read the Theodora panel in a new way? How do Andressecu-Treadgold and Treadgold critique previous interpretations of the imperial panels? How do they use archaeological/technical analysis together with texts to support a new identification of figures in the Justinian panel? What crucial changes do they note in the mosaic? Is their argument convincing? 8 March 7, 12 X. Seeing is believing: The "Loca Sancta" and the Arts of Pilgrimage Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai, Egypt, rebuilt by Justinian, ca. 543-65 (including mosaics of Moses and the Transfiguration of Christ) Reliquary Box Lid from the Sancta Sanctorum (now Vatican Museums, Rome), 6th-7th centuries Pewter Pilgrim’s ampulla from Holy Land with Crucifixion and Resurrection, 6th-7th century (Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC) Pewter Pilgrim’s ampulla showing Crucifixion with kneeling pilgrims and Women at Tomb (Monza Cathedral Treasury, ampulla 13) Pewter Pilgrim’s ampulla showing Locus Sanctus scenes (Monza Cathedral Treasury, ampulla 2) Qal’at Sem’an, Shrine of Symeon the Stylite the Elder, ca 480-490 Votive plaque silver gilt of Symeon Stylites the Elder, 6th century (Paris, Musée du Louvre) Terra-cotta Pilgrim’s Token of Symeon Stylites the Elder, 6th - 7th century (Berlin, Museum für Spätantike und Byzantinische Kunst–Staatliche Museen) Basilica of Hagios Demetrios, Thessaloniki, architecture, ca. 600; mosaics, ca. 620 Readings: Jas Elsner, Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity (Cambridge, 1995), 97-123; *Gary Vikan, “Byzantine Pilgrims’ Art,” in Linda Safran, ed. Heaven on Earth. Art and the Church in Byzantium (University Park PA, 1998), 229-263. Discussion: How does art shape the experience of the Byzantine pilgrim in different ways? How, according to Elsner, do the mosaics of Sinai (their iconography, placement and style) constitute a form of visual pilgrimage that reinforces the symbolic value of the pilgrimage site itself? How do the pilgrim’s ampullae and the Sancta Sanctorum reliquary box reinforce the pilgrim’s identification with the events of Christ’s life in a very tangible way once he/she has returned home? What relationship is established here between relic and image? March 14 XI. Liturgy, Display and Ideology: Ivories and Silver Vessels of the Sixth and Seventh Centuries Shepherd Plate, silver, 527-65 (Saint-Petersburg, Hermitage Museum) Hercules Plate, silver, 6th century? (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale) Silenus and the Maenad, 610-41 (Saint-Petersburg, Hermitage Museum) Cyprus Plates, originally from Lambousa, 628-30 (New York, Metropolitan Museum & Nicosia, Archaeological Museum) Kaper Koraon Treasure, buried after 605 Readings: Lowden, 79-83; *Ruth Leader, “The David Plates Revisited,” Art Bulletin 82, no. 3 (2000), 407-427. Discussion 9 What purposes do Byzantine silver and ivory objects serve with the Byzantine liturgy? What does Byzantine silver reveal about secular taste and continuities with Roman antiquity? How does Leader critique conventional interpretations of the David plates in terms of imperial ideology? March 19 XII. Early Byzantine Material Culture: Textiles, Amulets and Magic Woolen tapestry hanging with Dionysian deities, from Antinöopolis, ca. 500 (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art) Linen Tunic with tapestry-woven clavi and decorative panels depicting Dionysian motifs, ca. 400-450 (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art) Tapestry-woven hanging of Theotokos and saints in medallions, 6th century (Cleveland Museum of Art) Silk textile roundel with Annunciation, 6th-8th century (Vatican Museums) Round tapestry-woven Tunic Ornament with Narrative of Joseph, from Achmim, 6th-7th century (Trier, Städtisches Museum) Tapestry-woven Tunic roundel with David summoned to be anointed by Samuel,7th-9th century (Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery) Tapestry-woven Tunic hem with roundel showing David brought before Saul by Samuel half-roundels showing Holy Riders, 7th-9th century Silver arm-band with Christological scenes and amuletic motifs, 7th century Readings: *H. Maguire, “Garments pleasing to God,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 44 (1990):215-24; KL: Mango, Art of the Byz Empire, 50-51; *T. Dale, "The Power of the Anointed: The Life of David on Two Coptic Textiles in the Walters Art Gallery," Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 51 (1993):23-42. Discussion; To what extent do textiles, and the stamped or engraved objects considered here share the iconography of works of art made for the elite cultures of church and state, such as manuscript illumination and silver? How is the function of narrative transformed by its functional context on clothing or amulets, or as interior decoration for houses? March 21 ***MIDTERM EXAMINATION (Topics I to XI)*** March 23-31: Spring Break 10 April 2 XIII. Likeness and Presence: Portrait Icons before Iconoclasm Icons from Mt. Sinai: Pantocrator, encaustic on panel, 6th century Christ–“Semitic Type”, encaustic on panel, 6th century Saint Peter with medallions of Christ, Mary and John the Evangelist, encaustic on panel. 6th century Madonna and Child with angels, and Saints Theodore and George, encaustic on panel, 6th century Icon of Madonna and Child from Santa Maria Nova, Rome, 6th century (?) Icon of Enthroned Christ from Sancta Sanctorum, Rome, 7th century? Madonna della Clemenza, Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome, 705-07 Later Copies early Byzantine types: Hodegetria, ivory panel from Constantinople, 11th century copy of 5th-century? type (Utrecht, Rijksmuseum Het Catherijneconvent) Mandylion (face of Christ), San Bartolomeo degli Armeni, Genova, early 14th century Byzantine copy of 6th-century? type Mandylion, twelfth-century panel from Novgorod (Moscow, Tretyakov Gallery) Icon of Madonna and Child from Santa Maria Nova, Rome, 6th century (?) Icon of Enthroned Christ from Sancta Sanctorum, Rome, 7th century? Readings: Belting, 78-114; Mathews, Clash of Gods, 177-190. Recommended, especially for illustrations and commentaries on individual icons: K. Weitzmann, The Icon ( New York, 1978). Discussion: How did the Early Byzantine Church overcome the traditional Judeo-Christian resistance to fashioning portrait images of God and holy personages (prophets, saints...)? What continuities from the ancient, preChristian cult/ritual of images does Belting emphasize? How do Cormack Mathews call into question traditional interpretations of icons and their origins? April 4 XIV. Iconoclasm, the Cult and Theory of Holy Images Chludov Psalter, ca. 850 (Moscow, State Historical Museum MS grec. 129) Hagia Eirene, Constantinople: apse mosaic of cross, after 740 Hagia Sophia, Constantinople: inserted cross mosaic in the Seketron, ca. 770 Beresford Hope Cross, ca. 800 Fieschi Morgan Cross Reliquary, cloisonné enamel and silver gilt with niello, ca. 800 (New Readings: Belting, Likeness and Presence, 144-63; Mango, Art of the Byz Empire, 149-77. Discussion: What are the principal causes of iconoclasm? What theological arguments do the iconoclasts (opponents of icons) make against holy images and what justifications for icons do the iconoduels (proponents of 11 icons) offer in their defense? Come prepared to take sides and debate the merits of icons, using the texts included in Mango’s source collection. April 9 XV. The Macedonian “Renaissance”, Court Art and Ideology Hagia Sophia, Constantinople, mosaics installed 867 by Emperor Basil I (867-86) Apse mosaic of Theotokos; North Tympanum mosaics of patriarchs-general view -mosaics installed under Leo VI (886-912) -tympanum of southwest vestibule: Theotokos enthroned between Justinian and Constantine; narthex mosaic from tympanum over Imperial Door: Christ enthroned between Mary and the Archangel Michael with emperor prostrate Ivory Sceptre of Leo VI, 886-912 (Berlin, Museum für Spätantike und Byzantinische Kunst–Staatliche Museen) Ivory plaque showing Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos crowned by Christ, 944-59 (Moscow, Museum of Fine Art) Paris Psalter (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale MS grec. 139), ca. 950-70, made for Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos (?) Joshua Roll, ca. 950 (Rome, Vatican Library, MS pal. grec. 431) Ivory Plaque from rosette casket, ca. 950 (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art): Joshua and the Gibeonites Ivory Plaque of the Entry into Jerusalem, ca. 950 (Berlin, Museum für Spätantike und Byzantinische Kunst–Staatliche Museen) Ivory Plaque of the Washing of the Feet, ca. 950 (Berlin, Museum für Spätantike und Byzantinische Kunst–Staatliche Museen) Veroli Casket, ivory, ca. 950 (London, Victoria & Albert Museum) Painted Glass Bowl with classicising medallions, ca. 950 or 12th century (Venice, Treasury of San Marco) Troyes Casket, ivory casket with hunting scenes, 10th century Readings: K. Weitzmann, "The Character and Intellectual Origins of the Macedonian Renaissance" in Studies in Classical and Byzantine Manuscript Illumination. Chicago, 1971, 176-223; Alicia Walker, “Appropriation. Stylistic Juxtaposition and the Expression of Power,” in the Emperor and the World. Exotic Elements and the Imaging of Middle Byzantine Imperial Power (Cambridge, 2012), 45-79. Discussion: How do the accounts of the Macedonian “Renaissance” offered by Weitzmann and Webb differ in method and argument? To what extent do both style and content inform Byzantine imperial ideology? April 11 XVI. "Icons in Space": Middle Byzantine Church Decoration Monastery of Hosios Loukas, Katholikon, architecture and mosaics, early 11th century (before 1048) Ochrid, H. Sophia, apse, ca. 1050 Monastery of the Koimesis, Daphni (near Athens), ca. 1100 Church of Saint George at Kurbinovo, Yugoslav Macedonia, ca. 1190 12 Harbaville Triptych, ivory, 10th century (Paris, Musée du Louvre): Deesis and saints Ivory diptych with “Dodekaorton” or Twelve Feasts, 11th century (Saint Petersburg, Hermitage Museum) Menologion of Basil II, ca. 1000 (Rome, Vatican Library, MS grec. 1613), fol. 299v: Baptism Gospel Book, ca. 1100 (Parma, Biblioteca Palatina) Iconostasis Beam, tempera and gold leaf on panel: Deesis and Twelve Feasts (Monastery of St. Catherine, Mt. Sinai), twelfth-century Iconostasis Beam in enamel, originally from Constantinople (Pantokrator Monastery?), twelfth century (now forming upper zone of Pala d’Oro, San Marco, Venice) Reading: KL: Lowden, 229-270; KL: O. Demus, Byzantine Mosaic Decoration (London, 1948), 3-39; *T. Mathews, "The Transformation Symbolism in Byzantine Architecture and the Meaning of the Pantokrator in the Dome," in Church and People in Byzantium, ed., R. Morris (Birmingham, 1990), 191-214. *C. Barber, "From Transformation to Desire: Art and Worship after Byzantine Iconoclasm," Art Bulletin 75 (1993):7-16 Discussion: How does Otto Demus define the “classical system” of Middle Byzantine church decoration, and what essential relationships does he establish between art and architectural space/ art and the beholder? How does Mathews critique Demus and attempt to redefine the nature of Middle Byzantine church decoration; what does he see as the essential function of the Pantocrator in the dome vis-à-vis the spectator? How does Barber call into question Mathews’ interpretation of the Pantocrator? April 16 XVII. Late Antique, Byzantine and Russian Orthodox Art in the Chazen (Meet in Gallery I on second floor of Elvehjem Building, accessed from Paige Court) April 18, 23, 25 XVIII. Middle Byzantine Programmes in Foreign Courts 1) Building “Heaven on Earth” in the Kievan Rus Hagia Sophia, Kiev, constructed under Yaroslav the Wise (1019-54) St. Demetrios, Vladimir, 1193-97 Reading: KL Olenka Pevny, “Kievan Rus” in The Glory of Byzantium, 281-286 2) Byzantine Court Culture in Norman Sicily Palermo, Cappella Palatina: architecture and mosaics of the dome and transept, under Roger II, 1140-43. Martorana (St. Mary of the Admiral), Palermo: architecture and mosaics, for George of Antioch, ca. 1143 Cefalù Cathedral, sanctuary mosaics, 1148 Readings: KL: Lowden, 309-346; *W. Tronzo, “"The Medieval Object-Enigma and the Problem of the Cappella Palatina in. Palermo," Word and Image 9 (1993), 197-228. 3) Appropriation and Adaptation in Medieval Venice 13 Basilica of San Marco (the Ducal Chapel), Venice: architecture mainly completed 1094 (facade after 1204) Readings: KL: Belting, 195-207; *Thomas Dale, “Cultural Hybridity in Medieval Venice Reinventing the East at San Marco after the Fourth Crusade,” in San Marco, Byzantium and the myths of Venice, ed. H. Maguire and Robert S. Nelson (Washington, D. C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2010), 151-191. Discussion: How is Middle Byzantine church decoration adapted in different for specific ideological and religious reasons in the courts of the Kievan Rus, Norman Sicily and Venice? What distinctive meanings does “cultural hybridity” have and how is the concept applied differently by Tronzo and Dale? How do Tronzo and Dale take into account specific aspects of court ritual and privileged viewing in their interpretations? April 30 XIX. Crusader Art and Cultural Hybridity in the Holy Land KL: Glory of Byzantium, 389-401; Eva Hoffman, “Christian-Islamic Encounters on Thirteenth-century Ayyubid Metalwork: Local Culture, Authenticity and Memory,” Gesta XLIII/2 (2004):129-142 (online at http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/stable/pdfplus/25067100.pdf) Maria Georgopoulou, “Orientalism and Crusader Art: Constructing a New Canon,” Medieval Encounters 5, no. 3 (1999): 289-321 (online through MadCat). Discussion: How is “Crusader Art” usually defined? How do the metalwork and glass objects studied by Eva Hoffmann and Maria Georgopoulou further complicate the definition of “Crusader Art” in terms of production and intended audiences? How does Georgopoulou adapt Said’s concept of Orientalism to medieval Crusader Art? May 2 XX. The Shroud of Turin and Liturgical Images of the Passion ***Assignment 2 due*** Shroud of Turin, Byzantine textile icon, early 14th century Constantinople (now in Turin Cathedral) Saint Panteleimon, Nerezi (Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia), mural paintings, 1164 -Deposition and Threnos/Entombment of Christ “Our Lady of Vladimir”, icon of Virgin & Child “Eleousa”, 12th century, Constantinople (now Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow); back of icon showing Arma Christi Double-sided icon from Kastoria, 12th century: Hodegetria (front); Man of Sorrows (back) Saint George, Kurbinovo (Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia), mural paintings, 1191 -Threnos; apse showing con-celebration of bishops and Amons Aer King Abgar with the Mandylion, icon, St. Catherine’s, Mt. Sinai, ca. 950 Burial Shroud of King Milutin of Serbia (Belgrade, Museum of Church Art) Readings: 14 *W. Dale, "The Shroud of Turin: Icon or Relic?" Nuclear Instruments & Methods in Physics Research 29 (1987): 187-192; KL: S. uri, "Late Byzantine 'Loca Sancta'? Some Questions Regarding Form and Function of Epitaphioi," in Twilight of Byzantium. Princeton, 1991, 251-61. Discussion: Why does Dale argue that the traditional question of the authenticity of the shroud of Turin is a false one and how does he redefine the terms of debate? How did the image of the Threnos emerge and how did it prepare the way for a full-length image of the body of Christ? How does uri explain the function of related images on epitaphioi? May 7, 9 XXI. The Palaeologan Renaissance and the Collapse of the Empire Deesis mosaic, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, south gallery, ca. 1205 or 1261? Tekfur Saray (so-called “Palace of Constantine Porphyrogenitos”), extension of Blachernae Palace, Istanbul, ca. 1350 Fethiye Djami (St. Mary Pammakaristos), Istanbul, 1315 under Andronikos II Monastery of Gracanica (Serbia), pre-1321 for King Milutin Kariye Djami (Monastery of the Savior in the Chora), Istanbul: architecture of naos, ca. 1077-81 under Maria Ducas and restoration ca. 1100 under Isaac Comnenos; architecture of outer narthex and parekklesion and decoration (mosaics and frescoes), 1316-21 under Theodore Metochites Readings: KL: Lowden, 389-424; KL: Krautheimer/uri, Early Christian & Byzantine Architecture, 413-50 (esp. 440ff); Discussion: What impact did the political and religious climate of the late Byzantine empire have on the appearance of Byzantine art and architecture? What role is played by private patrons? ***Saturday May 18 at 10:05 a.m. to 12:05 pm: FINAL EXAM**** 15