Physics with Calculus/Mechanics/Scalar and Vector Quantities

Scalar and Vector Operations

ةهجتملا تايمكلاو ةيسايقلا تايمكلا

Contents

1 Introduction

2 Scalar Quantities

3 Vector Quantities

4 Unit Vectors

5 Vector Components

6 Vector Algebra o o

6.1 Negation

6.2 Scalar Multiplication o o o o

6.3 Addition

6.4 Dot Product

6.5 Cross Product

6.6 Useful Properties of Dot Product and Cross Product

Introduction

The study of physics is intimately tied in with the study of mathematics. Sometimes, the direction of a number or quantity is as important as the number itself. Mathematicians in the 19th century developed a convenient way of describing and interacting with quantities with and without direction by dividing them into two types: scalar quantities and vector quantities. Scalar quantities have a magnitude but no direction. Vector quantities have both a magnitude and a direction. For instance, one might describe a plane as flying at 400 miles per hour. However, simply knowing the speed of the airplane is not nearly as useful as knowing the speed and direction of the airplane, so a more accurate description may be a plane flying at 400 miles per hour southeast.

يانالا لونيلاو

ةحانسم

5 kg

ةفانضلإاب

.

scalar

ةينسايقلا تانيمكلا مولا لونيلا ن ي وني ونلى ا مينسقت نكمي )ةقتشم وأ ةيساسأ( ةيئايزيفلا

نسج ةن تك أ مونقت أ منام نطقف direction

ان هاجتا magnitude

رادقملاب اهديدحت

ايياا هاجتلاا ا لاوأ رادقملا ديدحتل ايجتحا هيأ ايه ظحلا

كمي ةيسايقلا ةيمكلا

ددنحت أ ولى جاتحت ة جتملا ةيمكلا امأ .ةيئايزيفلا ةيمكلا ايددح

ابرغ ا هاجتاو

.

vector

دق وكي

30 m2

تايمكلا عيمج

ة جتملا ةيمكلا

ة يطتسم ةعطق

10 m/h

حايرلا ة رس مام ناهرادقم ولى

Vector Quantity

Displacement

Force

Acceleration

Scalar Quantity

Length

Mass

Speed

1

Scalar Quantities

Scalar quantities are numbers that have a magnitude but no direction. Scalars are represented by a single letter, such as a . Some examples of scalar quantities are numbers without units (such as three ), mass ( five kilograms ), and temperature ( twenty-two degrees Celsius ).

Vector Quantities

Vectors are a geometric way of representing quantities that have direction as well as magnitude.

An example of a vector is force. If we are to fully describe a force on an object we need to specify not only how much force is applied, but also in which direction. Another example of a vector quantity is velocity -- an object that is traveling at ten meters per second to the east has a different velocity than an object that is traveling ten meters per second to the west. This vector is a special case, however,sometimes people are interested in only the magnitude of the velocity of an object. This quantity, a scalar, is called speed which has magnitude but no given direction.

When vectors are written, they are represented by a single letter in bold type or with an arrow above the letter, such as or . Some examples of vectors are displacement (e.g. 120 cm at

30°

) and velocity (e.g. 12 meters per second north ). The only basic SI unit that is a vector is the meter. All others are scalars. Derived quantities can be vector or scalar, but every vector quantity must involve meters in its definition and unit.

Unit Vectors

An illustration of common choice of unit vectors in a Cartesian coordinate system

Strictly speaking, vectors exist separately from any coordinate systems. As vectors are geometric objects, we do not need to define a coordinate system in order to talk about vectors—or even to perform most operations on vectors. For example, consider the triple of numbers: number of apples, number of bananas, and number of carrots you have. Say that you calculate the triple in one coordinate system and get (1,2,3). If you rotate your coordinate system, and recalculate, you will have (1,2,3) again. Thus, the triple does not have the most important property of a vector -- that is transform like the coordinate system.

2

Nevertheless, it is often convenient to introduce a coordinate system. In three dimensions, for many problems the rectangular, or Cartesian coordinate system (after French mathematician René

Descartes) turns out to be convenient, and this coordinate system can be defined in terms of unit vectors.

A unit vector is a vector pointing in a given direction with a magnitude of one. Essentially, it merely indicates direction. In a Cartesian system the three unit vectors are called i , j , and k (or, in handwriting, with a little "hat" on top, as , , and ). Colloquially, you might refer to the directions of the unit vectors as "east", "north", and "up". One could just have easily chosen i as up, j as east, and k as north. In choosing i , j , and k , once i and j are chosen, k must point to a particular direction, so that a common convention called "right-hand rule" holds. Mathematically, this can be compactly expressed as,

, but we will expand more on this as we describe "cross products" later on.

Unit vectors are generally chosen to be orthogonal. That is, each unit vector is perpendicular to each of the others. While unit vectors do not need to be orthogonal, working with a coordinate system defined by orthogonal unit vectors will be convenient in most cases. There are two other major coordinate systems used in physics—cylindrical coordinates and spherical coordinates.

These will be introduced at a later time as necessary.

Vector Components

Every vector may be expressed as the sum of its n unit vectors.

The quantities a x

, a y

, and a z

are called the vector components of vector A . Sometimes they are represented simply as an ordered triple (e.g. ( a x

, a y

, a z

)) especially when the choice and ordering of three unit vectors are not ambiguous.

3

Example of Vector Components

Finding the components of vectors for vector addition involves forming a right triangle from each vector and using the standard triangle trigonometry .

Vector Algebra

Negation

The vector sum can be found by combining these components and converting to polar form

Illustration of vector negation and scalar multiplication

Considering a vector represented graphically by an arrow, the negative of a vector would be represented by a vector of the same length but opposite direction.

Scalar Multiplication

4

Note that vector negation is merely multiplication by a scalar, where that scalar is -1. A scaled vector represented graphically would point in the same direction as the original vector but have its magnitude scaled by a factor of k .

Addition

Illustration of head-to-tail addition

Two vectors can be added graphically by placing the tail of the second vector (here, B ) coincidental with the tip of the first vector ( A ). The resultant vector A + B is the vector drawn from the tail of A to the tip of B .

Any number of vectors can be added in this fashion. Vector addition is commutative: and associative:

Graphical Vector Addition

5

Adding two vectors A and B graphically can be visualized like two successive walks, with the vector sum being the vector distance from the beginning to the end point. Representing the vectors by arrows drawn to scale, the beginning of vector B is placed at the end of vector A. The vector sum R can be drawn as the vector from the beginning to the end point.

The process can be done mathematically by finding the components of A and B, combining to form the components of R, and then converting to polar form .

Dot Product

When we multiply two vectors, we can either apply a multiplication rule that produces a scalar as the end result, or one that produces a vector as the end result. The first one that produces a scalar is called dot product . In mathematical texts, this is often called inner product , and some older texts will refer to this as scalar product (not to be confused with scalar multiplication); they are all the same. Dot product has all the usual properties of products, such as associativity, commutativity, and the distributive property. Geometrically, dot product is defined as:

, where θ is the angle between and . Note that since cos(0) = 1, if is parallel to , then

. On the other hand, since if is perpendicular to , then

. Using this as the guiding rule, we find below relationship:

.

Using this, we can define dot product in terms of component vectors as follows:

.

You are encouraged to expand out the multiplication explicitly, using the distributive property and find which terms cancel to zero and which products become 1.

6

Cross Product

The second multiplication rule for product of two vectors yields yet another vector. This multiplication rule is a very special one—in fact, it is a special property of 3-dimensional space that we can define a vector multiplication is this way and still obtain a vector. This rule will not work when limited to 2-D, and in any dimensions greater than 3, an extension of this rule will not result in another vector (cf. dot product can be naturally extended or limited to any dimensions to produce a scalar). This multiplication is called cross product , and in other texts, you may find terms outer product and vector product . The product can be defined with the two rules, first specifying the product vector's direction, and the second specifying its magnitude:

1.

is perpendicular to and (that is, perpendicular to the plane defined by these two vectors). This leaves two possible directions along the line perpendicular to the plane.

One of the two directions is called by a "right-hand rule": Hold out index finger, middle finger, and the thumb so that they are all perpendicular to each other. Let the index finger point towards direction of , and the middle finger towards . Then the thumb points towards the direction of . The ordering is important here (note exchanging A and

B makes the thumb point in the opposite direction).

2.

, where θ is again the angle between and .

Applying this definition to unit vectors again, we find following relationships:

And in terms of components, we have (after a tedious algebra):

.

It turns out we can write this complicated relationship as a determinant of a 3 x 3 matrix:

.

Some properties of cross product, such as derived as a property of the determinant of the matrix.

7

.

and can be

Summery

Physics is a mathematical science. The underlying concepts and principles have a mathematical basis.

Throughout the course of our study of physics, we will encounter a variety of concepts that have a mathematical basis associated with them. While our emphasis will often be upon the conceptual nature of physics, we will give considerable and persistent attention to its mathematical aspect.

The motion of objects can be described by words. Even a person without a background in physics has a collection of words that can be used to describe moving objects. Words and phrases such as going fast,

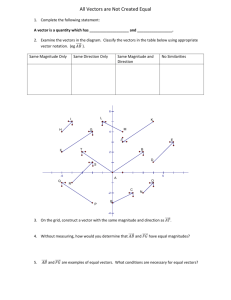

stopped, slowing down, speeding up, and turning provide a sufficient vocabulary for describing the motion of objects. In physics, we use these words and many more. We will be expanding upon this vocabulary list with words such as distance, displacement, speed, velocity, and acceleration. As we will soon see, these words are associated with mathematical quantities that have strict definitions. The mathematical quantities that are used to describe the motion of objects can be divided into two categories. The quantity is either a vector or a scalar. These two categories can be distinguished from one another by their distinct definitions:

alone.

Scalars are quantities that are fully described by a magnitude (or numerical value)

Vectors are quantities that are fully described by both a magnitude and a direction.

The remainder of this lesson will focus on several examples of vector and scalar quantities (distance, displacement, speed, velocity, and acceleration). As you proceed through the lesson, give careful attention to the vector and scalar nature of each quantity. As we proceed through other units at The Physics Classroom

Tutorial and become introduced to new mathematical quantities, the discussion will often begin by identifying the new quantity as being either a vector or a scalar.

Check Your Understanding

1. To test your understanding of this distinction, consider the following quantities listed below. Categorize each quantity as being either a vector or a scalar. Click the button to see the answer.

Quantity a. 5 m b. 30 m/sec, East c. 5 m., North d. 20 degrees Celsius e. 256 bytes f. 4000 Calories

Category

8

Useful Properties of Dot Product and Cross Product

9