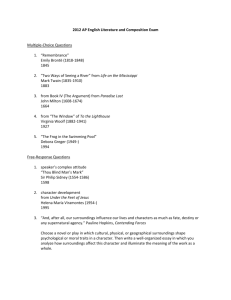

Tlatelolca women-SECOLAS 2012 ( DOC )

advertisement

Margarita Vargas-Betancourt University of Florida SECOLAS 2012 "Tlatelolca Women in the Quest for Land in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries" Paper presented at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Council of Latin American Studies, Center for Latin American Studies, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida. Land lawsuits, testaments, royal mandates, and other colonial documents indicate that during the viceroyalty of New Spain, Tlatelolca women were active land and house owners who sold, purchased, inherited, bequeathed, rented, and of course, fought over their posessions. The so-called conquest and the establishment of a colonial order originated changes that impacted women’s lives. Cases from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries suggest that although there was a great degree of violence from both indigenous peoples and Spaniards towards women landowners in Santiago Tlatelolco, the latter found ways of using the traditional indigenous land tenure system as well as the Spanish legal system to protect their property and their persons. VIOLENCE The last and bloodiest battles of the conquest were fought in Tlatelolco. After the Spaniards defeated the Mexica and their allies in Tenochtitlan, many of the Tenochca warriors retreated to Tlatelolco. Tlatelolca, Tenochca, and their allies resisted until Tlatelolco’s roads, bridges, water canals, and temples were destroyed. Many people died, especially men. These losses affected the lives of the women who survived, for instance that of Ana Papan and her daughters, residents of the barrio or tlaxilacalli (“political district”) of San Martín Atezcapan.1 On February 1572, they initiated a lawsuit against the Spaniard Gaspar Carrillo before the Real 1 According to Susan Schroeder, the term tlaxilacalli is commonly found in colonial documents. Unlike the term “calpulli” which referred to a unit of people, don Domingo de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin used tlaxilacalli to denote “political districts or jurisdictions.” The term “tlaxilacalli,” then, seems to connote “a territorial organization.” Fray Alonso de Molina defined it with the term “barrio.” Susan Schroeder, Chimalpahin and the Kingdoms of Chalco (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1991), 143-152. 2 Audiencia. They accused him of opening ditches and constructing a building on the land they owned in the barrio of San Martín Zacatlan.2 They stated that when they tried to stop him, he slapped them, stoned them, and screamed “putas indias viejas” (old whores). Finally he yelled “que se fuesen con el diablo” (go to the devil).3 The lawsuit suggests that the origin of the conflict went back to the conquest. According to the women’s witnesses, the disputed land and houses had belonged to Chimaltzin, an “officer” whose job was to take flowers to Moteuczoma. Chimaltzin bequeathed his property to his two sons: Maçapulcatl Chimaltzin and Atlatzin. The former died on Hernán Cortés’trip to Honduras. The latter died of the wounds that the Spaniards inflicted on him. Because of the war, Atlatzin’s widow Ana Papan and his daughters had fled from their house in San Martín Zacatla, like many other inhabitants of the same tlaxilacalli, and settled in San Martín Atezcapan where they had relatives. Since they had left the houses and land vacant, the tlaxilacalleque (elders of the barrio) of San Martín Zacatlan had given the land and houses to safeguard to Martín Coatl, an indio advenedizo (outsider) from Tenochtitlan. According to the Tlatelolca women and their witnesses, the barrio’s elders clearly stated that the property rights belonged to Chimaltzin’s descendants, and that Coatl and his descendants would have to give the land and houses back. However, several decades letter, Chimaltzin and Coatl’s grandchildren were involved in a bitter fight over the properties. In October 1573, the Real Audiencia issued a final judgment in favor of Ana Papan and her daughters. The president and oidores (superior court judges) of the Audiencia gave Gaspar Carrillo, the Spanish husband of Ana Papan’s daughters were Marina Susana, Barbola María, and Mençia Marta. Their property consisted on three houses and the corresponding solar (land located next to a house), AGN, Tierras, Vol. 20, Part 2, Exp. 1. 2 3 Ibid., ff. 106, 107. 3 Coatl’s granddaughter Andrea Ramírez, nine days to pay the rent he owed to the Tlatelolca owners of the houses he inhabited. Tlatelolca women not only competed with Spaniards over land and resources, but also with other indigenous people. On June 5, 1562, before the Real Audiencia, Juliana Tiacapan accused Pablo Suárez Hernández, both Tlatelolca, of taking away the three camellones de tierra (land for cultivation) that Juliana Tiacapan and Ana Xoco, her mother possessed and cultivated.4 According to Juliana Tiacapan, the original owner of the land was her grandfather Chimal. He had bequeathed it to his daughter Ana Xoco, who had continued cultivating it. In the meantime, Juliana married Pedro Yzqui and left her mother’s house to live with her husband and her mother-in-law, Marina Tiacapan. Upon the death of Pedro and Marina, Juliana went back to her mother’s house and helped her in the cultivation of the land. Unfortunately for Juliana, in her will, Marina fraudulently bequeathed the camellones that belonged to Ana and Juliana to her nephew Pablo Suárez. Pablo used the will to justify the appropriation of the disputed land and the subsequent attacks on Juliana, but Juliana had proven her case. She presented to the Audiencia a painting with the judgment that Oidor Herrera had issued in her favor in 1552 in a lawsuit between Juliana and another indigenous woman named Francisca, who had stolen some of Juliana’s corn. The result was that on June 12, 1562, Oidor Luis de Villanueva dictated a judgment in favor of Juliana and ordered Pablo to leave her alone. Pablo Suárez and his procurador (soliciter) appealed against the judgment. In fact, Pablo continued to harass Juliana. In August, she accused him of beating her and of stealing her hoe, and the Audiencia’s oidores ordered Santiago Tlatelolco’s alcaldes (municipal council’s judges) to protect her and to recover 4 AGN, Tierras, Vol. 2729, Exp. 20. 4 her hoe, and on January 11, 1563, they declared that the judgment in favor of Juliana was definitive. In a lawsuit that began in 1592, María Jerónima accused Antonio Joseph and his wife Magdalena Inés, all of them residents from the barrio of Santa Ana Huitzilan, of destroying a wall, tearing down a fence, and closing the entrance and exit to one of her houses. María Jerónima proved that she had inherited the property from Ana Suárez, her aunt, who in turn had inherited it from her aunt Angelina de la Cruz. In 1562, Angelina de la Cruz had bought the land and houses involved in the legal process from Juan Quauhtzetzeltzin. Since María Jerónima presented the bill of sale and the testaments, the Real Audiencia issued a judgment in her favor.5 LAW The women from the three cases discussed suffered physical and verbal attacks, but they used the evolving colonial legal system to obtain protection for themselves and their property. Like them, many other Tlatelolca women went before Spanish courts to defend their land. In the sixteenth century, they took their cases to the Real Audiencia, but by the end of this century and throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they also took their conflicts to the Juzgado de Indios (General Indian Court).6 For instance, circa 1558, María Teccho and Marina Tlacohch, residents of the barrio of San Sebastián Atzaqualco, fought over land in Atlixocan before the It is interesting to point out that Juan Escalante, María Jerónima’s husband, was a Spaniard. AGN, Tierras, Vol. 56, Exp. 8. 5 The Real Audiencia was a royal judiciary institution that sought to protect the king’s subjects at the local level. It consisted of “eight oidores, or superior judges, four regular judges who heard criminal and civil matters, two prosecutors, one civil, one criminal, a chief bailiff, a chief chancellor, and a variety of ancillary personnel, as we as notaries, interpreters, and procuradores (soliciters) on behalf of Indian petitioners.” Brian P. Owensby, Empire of Law and Indian Justice in Colonial Mexico, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), 43. 6 5 Real Audiencia.7 In 1564, in a bill of sale, doña María and don Pedro Dionisio, residents of the barrio of San Pablo Teocaltitlan, accused Simón and María, Santiago Tlatelolco residents, of occupying and building houses in their land.8 In 1573, Ana Xocoton initiated a lawsuit against Antón de San Francisco;9 circa 1583, María Menor followed a lawsuit against María Musiel and other indigenous women over a house and land in the barrio of San Sebastián Tzacualco.10 By the last decades of the sixteenth century, indigenous peoples were unhappy with the results obtained at the Audiencia. The legal crisis was so serious that Viceroy don Luis de Velasco the younger asked the king to establish a special court for the conflicts of the natives. The result was the creation of the Juzgado General de Indios in 1590. The viceroy and a legal assistant administered the Indian Court. It had jurisdiction over administrative petitions. Lawsuits among indigenous peoples and lawsuits from Spaniards against natives were considered as such, whereas cases brought from indigenous peoples against Spaniards were considered as judicial, and thus, fell under the jurisdiction of the Real Audiencia. Because of the effectiveness and the speed of the Juzgado, natives began to prefer it. They learned that if they filed their petitions under the category of administrative, these would go to the Juzgado, even cases against Spaniards.11 7 On 1563, the Real Audiencia dictated a judgment in favor of Maria Teccho. AGN, Tierras, Vol. 20, Part 2, Exp. 4. 8 AGN, Tierras, Vol. 22, Part 1, Exp. 5. 9 AGN, Tierras, Vol. 35, Exp. 1. 10 AGN, Tierras, Vol. 48, Exp. 4. 11 Owensby, Empire of Law and Indian Justice, 43-44. 6 As early as 1590, Magdalena Atesca and her four brothers sought the protection of the Juzgado de Indios. They accused the Spaniard Francisco Martín and his son-in-law of trying to take away from them the land that they had inherited from their parents, located in the barrio of Petlachiucan, near Azcapotzalco.12 In 1592, Angelina, a resident of the barrio of San Martín explained to the Indian Court that some people wanted to seize from her the houses she owned in a place known as Tlilguacan.13 The trend for indigenous people to take their property conflicts to the Juzgado continued into the seventeenth century. In 1603, Francisca María and her husband Antonio, residents of Santiago Tlatelolco, explained that they had a stall in Mexico City’s market where they sold jubones de olandilla (linen doublet) and mantas de la tierra (cotton mantles). The sale of these products sustained them and allowed them to pay their tribute, but they complained to the Indian Court that some Spaniards wanted to take their stall away.14 In 1662, Angelina María, resident of the barrio of Atempa, declared to the Juzgado that as the encomendera (holder of an encomienda grant) of Sacatlan, she received eggs, xocotes (a type of fruit), and ropa de la tierra (probably cotton mantles too). She sold these products for her sustenance; however, she complained that officers, such as ministros de vara (judicial officers) and alguaciles (bailiffs), used her house as a hostel and consumed her goods.15 For this reason, she could not profit from her encomienda.16 As seen in one of the cases above, Tlatelolca 12 AGN, Indios, Vol. 3, Exp. 124. 13 AGN, Indios, Vol. 3, Exp. 336. 14 AGN, Indios, Vol. 12, Exp. 119. For more on the term vara de oficio (“staff of office”) see Owensby, Empire of Law and Indian Justice, 227-230. 15 16 AGN, Indios, Vol. 19, Exp. 462. 7 merchants, whose selling booths were now located in Mexico City’s markets, often sought the protection of the Juzgado. In 1685, Francisca Monica, her daughters Nicolasa Francisca and María de los Angeles, and her daughter-in-law María Nicolasa, sold vegetables and other produce in a stall they had in Mexico City’s Plaza Mayor. Francisca Mónica’s husband Andrés Nicolás, principal of Santiago Tlatelolco, complained to the Indian Court that some people were trying to prevent his wife and daughters from selling in their stall.17 In all of the cases above, the Juzgado de Indios granted the protection of the viceroy to the petitioners without the lengthy time involved in lawsuits before the Audiencia. TRADITION There are some prevalent themes in the cases that women did take before the Real Audiencia; for instance, patrimonial versus purchased land, conflicts between Spaniards and indigenous peoples, and conflicts between commoners and nobles. The trend that emerges from the analysis of different cases is that one of the strongest arguments that indigenous people used to defend their property was that of patrimonial land. In the Nahua tradition, patrimonial land or huehuetlalli (when it is in the possessive) refers to land that was inherited.18 In the first two lawsuits discussed, the argument that turned the case in favor of Ana Papan and her daughters in the conflict with the Spaniard Gaspar Carrillo, and of Juliana Tiacapan in the conflict with the native Pablo Suárez, was that they had inherited the land in question.19 The conflict between Angelina Verónica, tutor to the heirs of a wealthy female merchant, and doña María Coatonal, 17 AGN, Indios, Vol. 29, Exp. 81. H.R. Harvey, “Aspects of Land Tenure in Ancient Mexico,” in Indians of Central Mexico in the Sixteenth Century, eds H.R. Harvey and Hanns J. Prem (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984), 86-87. 18 19 AGN, Tierras, Vol. 20, Part 2, Exp. 1; AGN, Vol. 2729, Exp. 20. 8 niece of don Diego Mendoza de Austria Moteuczoma, a renowned governor of Santiago Tlatelolco, was more complex.20 The reason for this is likely the involvement of a woman who belonged to a very prestigious Tlatelolca and Tenochca lineage: the Mendoza de Austria Moteuczoma.21 The conflict between Angelina Verónica and doña María Coatonal highlights two dichotomies, the one between patrimonial versus purchased land, and the one between commoners and nobles. In April 1584, Angelina Verónica initiated a lawsuit against doña María for appropriating eighty brazas (one braza was approximately six feet) of land located in the Don Diego’s lineage has generated a great deal of controversy. He was Santiago Tlatelolco’s governor from 1549 to 1562, and he appears in many colonial documents and codices, such as the Códice de Tlatelolco, the Códice Cozcatzin, the Códice García Granados. In addition, throughout the viceroyalty, his heirs initiated lawsuits to defend the lands that belonged to the cacicazgo. Like him, they claimed that don Diego was Cuauhtémoc’ son. Although the Spanish monarch recognized his right to Santiago Tlatelolco’s cacicazgo as Cuauhtémoc’s heir, scholars have questioned the legitimacy of don Diego’s claim. Robert H. Barlow and Amos Megged qualify him as a “native impostor.” One of the reasons for this is that in the Crónica Mexicáyotl, Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc stated that don Diego Mendoza was the son of Zayoltzin, a Tlatelolca prince. Another reason for this is that the original royal mandate that the king issued to acknowledge don Diego’s cacicazgo seems to have been lost. The copies that remain were those used by don Diego’s heirs in their lawsuits, and they indicate that the date of the original document was October 2, 1525. For further discussion on don Diego see Robert H. Barlow, Tlatelolco. Fuentes e Historia, vol. 2 (Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Universidad de las Américas, Puebla, 1989), 148; Amos Megged, “Cuauhtémoc’s Heirs,” Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 38 (2007): 368; Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc, Crónica Mexicáyotl (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, 1975), 172; Rebeca López Mora, “El cacicazgo de Diego de Mendoza Austria y Moctezuma: un linaje bajo sospecha” in El cacicazgo en Nueva España y Filipinas, eds Margarita Menegus Bornemann and Rodolfo Aguirre Salvador (Mexico City: Centro de Estudios sobre la Universidad, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Plaza y Valdés, S.A. de C.V., 2005), 213, 216, 221, 230-231; Emma Pérez-Rocha and Rafael Tena, La nobleza indígena del centro de México (Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2000), 80. 20 21 AGN, Tierras, Vol. 49, Exp. 5. 9 pago (“sizable tract of land”) known as Aztacolcatlali.22 According to Angelina Verónica, doña María Coatonal had illegally sold a piece of her grandchildren’s land to the Dominicans who lived in Azcapotzalco. She requested the restitution of such land. For some years the two parties were unable to find a solution to the problem because both seemed to be legitimate claims. On one hand, Angelina Verónica claimed that her grandchildren had received the land in question from their great-grandmother Angelina Martína, a wealthy pochteca (merchant) who had bought it in 1551 from don Baltasar Tlilancalqui, a cacique (ruler) of Santiago Tlatelolco. In the bill of sale, he qualified this land as pillalli (“private, alienable, and tribute-exempt lands of the nobility”),23 and he specified that he had gotten it from his great-grandparents. On the other hand, doña María Coatonal claimed to have inherited the land from her father who had been a cacique of one of the most renowned lineages in Tlatelolco. Both, then, fought over land whose ultimate origin was patrimonial. To be more specific, the land they were fighting for had been personal land that had belonged to precontact ruling lineages. Nevertheless, in Angelina Verónica’s case, a commoner had bought this land, whereas doña María Coatonal had inherited it. At first, the case went to don Juan de Austria, governor of Santiago. After each side presented its witnesses, and after surveying the land, on October 20, 1584, don Juan dictated a sentence in favor of Angelina Verónica’s grandchildren and nullified doña María Coatonal’s sale of land to the Dominicans. However, things got quite complicated. At the beginning of 1585, 22 James Lockhart, The Nahuas after the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992), 145, 151. H.R. Harvey, “Aspects of Land Tenure in Ancient Mexico” in Indians of Central Mexico in the Sixteenth Century, eds H.R. Harvey and Hanns J. Prem (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984), 86-87. 23 10 doña María Coatonal appealed to the Real Audiencia against don Juan de Austria’s resolution. The Audiencia sent the problem back to Santiago’s governor. He went to the disputed land and made a new distribution among the litigants, but doña María disagreed with it, and appealed again to the Real Audiencia. Finally, the Audiencia required don Antonio Valeriano, the indigenous governor of Mexico City, to issue a final resolution. He concluded that the land of the conflict belonged to doña María. Don Juan de Austria’s decisions seemed to have followed Nahua standards, for they were based on Santiago Tlatelolco’s people’s consent. According to Lockhart, the main difference between European and Nahua land systems was that community consensus was much more important in the latter. The presence of local rulers and elders was an essential part of land transfers because they represented the opinion and the community’s public approval.24 Don Juan corroborated Angelina Verónica’s statement with that of other members of Santiago Tlatelolco, such as elders and cabildo officers. They all agreed that the land had belonged to don Baltasar Tlilancalqui who had sold it to Angelina Martína thirty years ago. They added that she had always cultivated this land, and that she had bequeathed it to her great grandchildren. Finally, they declared that doña María Coatonal and her husband had never possessed the aforesaid land. Nevertheless, instead the Audiencia took away don Juan’s jurisdiction over the case and passed it on to don Antonio Valeriano, governor of Mexico City’s indigenous cabildo. On the other hand, doña María also used an indigenous traditional mechanism for land tenure: the rights of nobles over patrimonial land. She claimed that she had inherited the disputed land from her father don Francisco Yquinopilci, who had inherited it from his father Tzihuac 24 Lockhart, The Nahuas after the Conquest, 149. 11 Popocatzin.25 The latter was a Tlatelolca noble who had participated in the wars that the Mexica fought against the people of Quauhtitlan under the leadership of Moteuczoma. As a reward, Moteuczoma granted land to Tzihac Popocatzin, who in turn bequeathed the land to his descendants. These were the property rights that doña María claimed to have. The fact that the Audiencia took away Santiago Tlatelolco’s governor’s jurisdiction over this case suggests that the president and oidores wanted to favor doña María Coatonal. They transferred the case to don Antonio Valeriano, who had no problems favoring her. The Audiencia and the indigenous governor of Mexico City sided with a woman who was not only noble but belonged to one of the most renowned lineages of the Mexica. This event was hardly innovative. The break with tradition can be found in the fact that doña María had already sold her “patrimonial” land to Spaniards. She did not fight over this land in order to bequeath it to her children and grandchildren, but to sell it. CONCLUSIONS The cases analyzed for this paper suggest that it was common for Tlatelolca women to possess, acquire, and transfer property. Additional research will determine whether during the viceroyalty, women in Tlatelolco had broader access to land and resources than indigenous women from other regions. Two facts suggest that this might be plausible. The first is the presence of wealthy women. Some of them were merchants, a legacy from Tlatelolco’s renowned precontact market; whereas as others were noble members of the powerful lineages that had and, to some degree, continued to rule Santiago Tlatelolco. Second, it is likely that men 25 Tzihuac Popocatzin was also the grandfather of don Diego Mendoza de Austria Moctezuma. For a discussion on the origins and cacicazgo of don Diego see footnote 21. 12 constituted most of the casualties of the battles fought over Tlatelolco in 1521. This might have resulted in a larger number of female landowners than before. In addition, the analysis of women in their quest for land and resources suggests that women adapted rapidly to a changing world. They found ways to preserve the indigenous land tenure system, for instance, by bequeathing land to their children and relatives and by defending their patrimonial rights before indigenous officers and Spanish courts. At the same time, they adopted innovative mechanisms that ensured their access to resources and their insertion in a monetary economy. Women started to buy land as early as 1521,26 and throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries they sold land to indigenous people but increasingly more to Spaniards. 26 Such an early date suggests that the sale of land started before the arrival of the Spaniards. AGN, Tierras, Vol. 17, Part 2, Exp. 4.