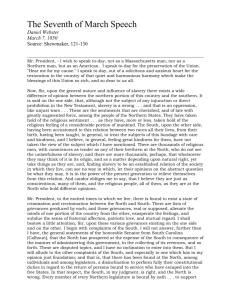

book review - New England Law

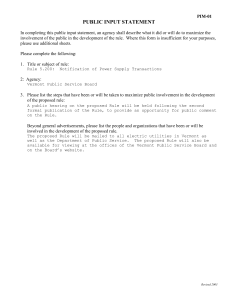

advertisement