expert's statement

advertisement

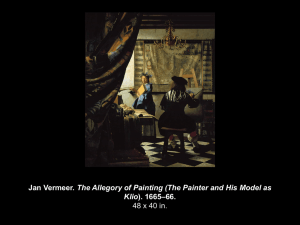

1 Statement opposing the export of: Raffaello Sanzio, called Raphael (Urbino 1483-1520 Rome) Head of a muse black chalk over pounce marks, traces of stylus, watermark encircled Saint Anthony's cross 12 x 8¾ in. (30.5 x 22.2 cm.) Condition: Generally good Provenance Gosuinus Uilenbroek, Amsterdam, by 1725; probably his sale, Beukelaar, Amsterdam, 23 October 1741, lot F.65, 'Vrouwe Hooft levens groote, met swart kryt van den zelven [Rafael]' (sold for 6.15 florins). Lady Bentinck (according to the Woodburn's Gallery exhibition in 1836). Sir Thomas Lawrence (L. 2445), with Woodburn's Gallery, London; from whom purchased by The Prince of Orange, later King William II of Holland; his sale, The Hague, 19 August 1850, lot 24, 'RAPHAEL. La soeur de Raphael, dessin à la pierre d'Italie. La resemblance entre ce portrait et les Madonnes du peintre, fait présumer que la soeur lui a servi souvent de modèle' (500 florins to Colnaghi). with Colnaghi, London, 1850. Boulton Collection (according to Ruland, loc. cit.). M. Marignane (L. 1872); from whom purchased by an English collector, in or before 1936. Literature J.A. Crowe and G.B. Cavalcaselle, Raphael: his life and works. With particular reference to recently discovered records, and an exhaustive study of extant drawings and pictures, London, 1882, II, p. 87 O. Fischel, 'Some Lost Drawings by or near to Raphael', The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, XX, February 1912, p. 299, no. 15 O. Fischel, Raphael's Zeichnungen, V, 'Römische Anfänge und die Decke der ersten Stanze, Der Parnass, Die Jurisprudenz', Berlin, 1924, no. 253 O. Fischel, 'Raphael's Auxiliary Drawings', The Burlington Magazine, LXXI, October 1937, p. 167, pl. 1A A. Scharf, 'The Exhibition of Old Master Drawings at the Royal Academy', The Burlington Magazine, XCV, November 1953, p. 352 R. Cocke and P. de Vecchi, The complete paintings of Raphael, New York, 1969, p. 103, ill. A. Forlani-Tempesti, 'The Drawings', in M. Salmi, The Complete Works of Raphael, New York, 1969, no. 127. L. Dussler, Raphael, a critical catalogue of his pictures, wall paintings and tapestries, London, 1971, p. 76. M. Prisco and P. de Vecchi, L'opera completa di Raffaello, Milan, 1979, p. 103, ill. P. Joannides, The Drawings of Raphael with a complete catalogue, Oxford, 1983, no. 245. E. Knab, E. Mitsch and K. Oberhuber, Raphael, Die Zeichnungen, Stuttgart, 1983, no. 378. F. Ames-Lewis, The Draftsman Raphael, London, 1986, pp. 37, 98-9, fig. 118 C. Bambach, Drawing and Painting in the Italian Renaissance Workshop: Theory and Practice, 1300-1600, Cambridge, 1999, pp. 324 and 485, note 95. A. Emiliani and M. Scolaro, Raffaello: La Stanza della Segnatura, Milan, 2002, p. 48, ill. 2 Waverley Criteria Waverley 2: Is it of outstanding aesthetic importance? Oskar Fischel, the greatest early 20th century scholar of drawings by the Urbino-born artist, described the Head of the Muse as ‘one of Raphael’s most beautiful women’s head’. The appreciation of Fischel for the quality of the drawing is echoed by other scholars who have a wide-experience of Raphael’s entire graphic corpus. For example, Francis Ames-Lewis in his 1986 monograph on the Italian’s drawings described the study in glowing terms: ‘the exquisite, sensuously drawn head for one of the Muses in the Parnassus’. The drawing encapsulates many of the qualities that make Raphael one of the most admired and imitated draughtsman. There is no better example of the artist’s ability to blend together seamlessly idealised beauty, based on his attentive study of classical sculpture, with naturalistic observation, seen in details such as the detailed rendering of the structure of the eye or the stray strands of hair that fall from her cap. This type of female beauty developed in drawings such as the Muse was to become canonical in academic art throughout Europe for centuries. Raphael’s particular concentration on the eyes in the drawing emphasises the drawing’s function as a study of expression, the sense of intelligence and inner animation being a key feature of Raphael’s art that he developed from his analysis of Leonardo da Vinci. The influence of his bitter rival, Michelangelo, is discernible in the knitted crosshatching used for the shadow on the far cheek and the drawing styles of the two artists working simultaneously in the Vatican would never be closer. It should be remembered that for the first half of the ceiling (1508-10) Michelangelo favoured black chalk for his figure studies. In Raphael’s case the use of the more tonally sensitive medium of black chalk was linked to the fresco’s position above the window. In order to combat the glare from the window Raphael emphasised the contrast between shaded and highlighted areas in the fresco. Raphael’s awareness and sensitivity to lighting comes across strongly in the study thanks to its relatively good condition, the artist skilfully using the cream of the untouched paper as a highlight. Waverley 3: Is it of outstanding significance for the study of some particular branch of history? The drawing is a study for a figure in Raphael’s Parnassus fresco in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican, his first Roman commission and the one for which he was called to the Papal capital city to execute. Raphael’s ability to transform abstract ideas (the frescoes are inspired by the subject classification of the books in the papal library housed in the room) into vital and engaging pictorial compositions depended on his skills as a designer in pen and chalk. The steps that led to the finished compositions on the walls and ceiling of the room can be followed in 60 preparatory drawings for the commission: 33 of them in Continental museums and the remaining 27 divided between Windsor Castle (5), the Ashmolean (15) and the British Museum (7). These represent a fraction of the number he must have made but nonetheless they offer the most complete record of Raphael’s working methods of any fresco project in his career. 3 The outstanding collection of Raphael’s graphic work in UK museums includes 4 of the 11 studies related to the Parnassus in Paul Joannides’ monograph on the artist’s drawings. The Muse is unique among the artist’s studies for the Stanza della Segnatura decorations because it the only known ‘auxiliary cartoon’. Such specialised studies of heads were made right at the end of the design process just prior to working on the wall itself. From the absence of pricking around its contours it can be assumed that Raphael wished to preserve it in a pristine state so that he could copy it freehand when painting the head in the wet plaster. Raphael’s use of a pounced cartoon as the basis for the drawing eloquently conveys the multi-layered complexity of his preparatory process. The proximity of the drawing to Raphael beginning work on the fresco adds to its appeal, especially as the head on the paper is unquestionably all his work while the corresponding detail on the wall has been altered by the passage of time and restoration. For an understanding and appreciation of the significance of Raphael’s skills as a draughtsman/ designer in underpinning his triumphant success in the Stanza della Segnatura that launched his meteoric rise in papal Rome, the Muse drawing has few rivals.