Review of Accounting

advertisement

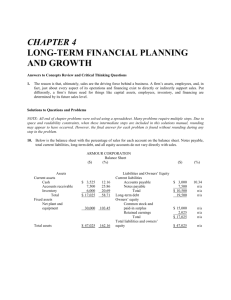

ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES

The understanding of the structure and integration of financial statements is crucial to

the ability to construct comprehensive proforma projections and forecast cash flows. Even

when a firm has the option of using cash basis accounting for tax purposes, lenders and

investors generally prefer accrual accounting since it more accurately reflects the economic

performance experienced by the firm. Moreover, in the endeavor to attract capital, the integrity

of the proforma financial statements is often used as a surrogate (rightly or wrongly) of the

integrity of the financial performance projections themselves. If the basic accounting figures

are not correct, why should the projections market share, costs, etc., be considered any better?

While the cash flows are of tantamount importance from an investment/valuation

perspective, the generation of the cash flows is relatively simple once the income statements

and balance sheets have been generated. The initial focus will, therefore, concentrate on these

two items and the construction of the actual cash flows will conclude.

Income Statements

The first question that must be asked of each economic occurrence is whether or not

the transaction is an item that appears on the income statement. Two important concepts are

involved in this determination.

Revenue Recognition -- The Revenue Recognition Principal states that revenue is recognized,

and recorded on the income statement, when it is reasonably assumed that the sale has

occurred and the proceeds will be collected.

Any bad debt expense (i.e., that portion of the revenues that is not expected to be

collected is ultimately deducted as an expense item. (Estimated bad debt expense is

maintained in the Allowance for Doubtful Accounts category until that time at which it is actually

deducted.)

Matching Principal -- The matching principal states that expenses will be recognized and

matched to the revenues (or benefits) generated by the incurrence such expense.

The most obvious category with regard to matching expenses to the revenues is that of

Cost of Goods Sold, a variable expense. Fixed expenses, such as rent, are more directly

related to the benefit aspect of this definition, for example the benefit of using the building that

the firm occupies is recognized during the period and not related to the revenues generated.

In general, a firm keeps at least two sets of books; one is for tax accounting purposes

while the other is for financial accounting (or managerial) purposes. Tax structures represent

government attempting to accomplish two primary objectives. First, the tax structure is trying to

set up broad categories to represent the "average" of all taxpayers affected when the reality is

there are millions of individual, specialized circumstances. Consequently, the statutory rates of

depreciation on equipment is based upon average use and does not allow for differences

between the firm that operates eight hours per day, five days per week and the firm that

operates twenty-four hours per day and seven days per week. The differences are ultimately

adjusted for upon the disposal of the asset, just as inventory adjustments are made at the end

1

of the period when a physical count is made. The second purpose of tax policy is for

social/economic engineering purposes. The graduated tax rate is an example where small

companies are encouraged through lower tax rates until they reach a certain level of

profitability, at which point the tax rate is increased to an above-average level to actually

recover the taxes at the lower rate until to the total taxes on all companies amounts to 34%.

Personal tax rates, on the other hand, are designed to redistribute wealth from higher income

earners to lower income earners. From a financial perspective, the objective is to avoid taxes

(first) or at least delay taxes. There is nothing wrong with utilizing the tax code to its fullest in

order to avoid taxes (as opposed to evade taxes, which is illegal) since there is an underlying

social/economic purpose behind the rules.

Taxation is a complex area. UTSA offers a Masters of Taxation and it is beyond the

scope of this note or this course to cover it in any detail. For purposes of the remainder of this

note, it will be assumed that the tax and financial reporting sets of books are one and the same.

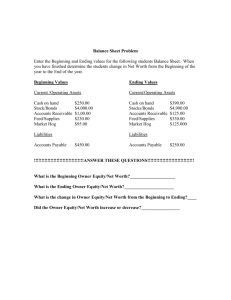

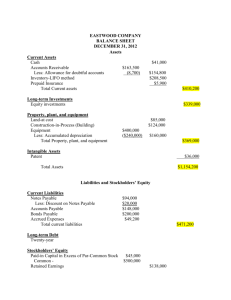

Balance Sheets

The balance sheet is not nearly as difficult to construct as it may appear. There is a

simple rule that must be kept in mind -- that it is called a balance sheet because the total assets

side of the balance sheet must equal (balance) the total liabilities and equity side of the balance

sheet. That means that the following rules apply:

(1)

Any increase (decrease) in an asset account must be exactly matched by an increase

(decrease) in a liability/equity account OR matched by a decrease (increase) in another

asset account.

Conversely,

(2)

Any increase (decrease) in a liability/equity account must be exactly matched by an

increase (decrease) in an asset account OR matched by a decrease (increase) in

another liability/equity account.

The confounding feature here is when a transaction occurs that appears on the income

statement. Keep in mind that the income statement ultimately flows through to the retained

earnings account. Thus, any revenue item which adds to net income also adds to retained

earnings while any expense item that deducts from net income also deducts from retained

earnings. (Remember, also, that there is a tax consequence associated with changes in net

income, but this is easy to deal with through the income statement.)

Every double-entry must result in the balance sheet remaining balanced. Consider the

expenditure of $100 of cash for 1) inventory; 2) payment of accounts payable; or 3) repair and

maintenance. In any event, cash is decreased by $100. The offsetting entry occurs on the

balance sheet as indicated in the following diagram (where the superscript represents which

account is affected by the second entry and the { } signifies the effect of the entry):

2

Balance Sheet

Cash

Accounts Receivable

Inventory

Total Current Assets

Income Statement

-

100

Revenues

Cost of Goods Sold

Gross Profit

+ 1001

Net Fixed Assets

Net Goodwill

Total Assets

{ 0 }1or -100

Accounts Payable

Notes Payable

Taxes Payable

Total Current Liabilities

-

1002

Gen. & Adm. Expense

Salaries

Rent

Repairs & Maintenance

Utilities

Depreciation

Operating Income

+ 1003

Interest Expense

Taxable Income

Taxes

Long-term Debt

Net Income

Common Stock

Retained Earnings

Total Common Equity

Total Liabilities & Equity

{-100}3

Impact on Retained Earnings

via Income Statement

{-100}2

The first thing that lenders and investors look at in proformas (as do finance and

accounting professors) is whether or not the retained earnings figures on balance sheets and

the income statements between successive balance sheets are consistent with one another.

The relationship is easy:

Beg. Retained Earnings + Net Income - Dividends = End. Retained Earnings

The retained earnings account is simply a history of all income of the company since its

inception, less any income paid out as dividends to shareholders.

A Simple Example

Let's illustrate some basic principles of accounting with a simple example of starting a

company and following the impact on the financial statements that occurs as various events

transpire.

3

January 1, 2002

Gary has in mind starting a company that will produce and sell clocks. The first thing he

does is to incorporate his company (after conducting a name search) by filing the articles of

incorporation with the Secretary of State and paying a fee of $300.00 for the filing and $600.00

to an attorney for drawing up the papers. These fees are not a deductible expense in full

immediately since they are costs incurred in organizing the firm which has a perpetual life. The

internal revenue code allows amortization of capitalized organizational costs over a fifteen-year

period. Although it is common for companies to wait until year-end to recognize depreciation

and amortization expense, it should be recognized at the end of each month to more accurately

depict economic performance. The first entry recognizes the organization of the firm and its

source of financing. (Note that the term "Common Equity" will be employed for all forms of

external contributions of equity.) Accountants would actually make two separate entries in

order to recognize that this represents two separate transactions, one with the state as payment

of the filing fee, and the second with the lawyer as payment for the legal services involved in

organizing the firm.

Entries

Capitalized Organizational Costs

Common Equity

+900

+900

Assets

Organizational Costs

900

Total Assets

900

Liabilities & Equity

Common Equity

900

Tot. Liab. & Equity

900

4

(0+900)

(0+900)

January 2, 2002

Gary next opens a checking account and deposits $49,100 so that he can issue himself

an even 50,000 shares of stock ($1 par).

Entries

Cash

Common Equity

+49,100

+49,100

Assets

Cash

Organizational Costs

Accum. Amortization

Net Organizational Costs

49,100

900

( 0)

(0+49,100)

(This category is utilized later.)

900

Total Assets

50,000

Liabilities & Equity

Common Equity

Retained Earnings

Total Equity

50,000

( 0)

50,000

Total Liab. & Equity

50,000

5

(900+49,100)

January 3, 2002

Gary signs a lease to rent industrial space for manufacturing the clocks and housing the

corporate offices. The lease requires a deposit of $1,000 and monthly rent of $2,500 dollars

due at the end of each month. In addition, he arranges for utility and telephone connections

requiring deposits totalling $300. These transactions are recorded as follows (again, this is

really two transactions):

Entries

Cash

Deposits

- 1,300

+1,300

Assets

Cash

Deposits

Organizational Costs

Accum. Amortization

Net Organizational Costs

47,800

1,300

900

( 0)

900

Total Assets

50,000

Liabilities & Equity

Common Equity

Retained Earnings

Total Equity

50,000

( 0)

50,000

Total Liab. & Equity

50,000

6

(49,100-1,300)

(0+1,300)

January 4, 2002

Gary next buys $8,000 worth of clock parts (faces, hands, mechanisms) and clock

bases.

Entries

Cash

Materials Inventories

- 8,000

+8,000

Assets

Cash

Inventories

Materials

Total Current Assets

Deposits

Organizational Costs

Accum. Amortization

Net Organizational Costs

39,800

(47,800-8,000)

8,000

47,800

(0+8,000)

1,300

900

( 0)

900

Total Assets

50,000

Liabilities & Equity

Common Equity

Retained Earnings

Total Equity

50,000

( 0)

50,000

Total Liab. & Equity

50,000

The deposits are not recorded as a current asset since they will not be refunded until Gary's

business has established itself, a period of two to three years.

7

January 5-18, 2002

Gary hires a secretary for $1,500 per month and a salesperson for $1,200 plus a 10%

commission to help run operations. Since Gary anticipates that there will be an occasional bad

debt expense from customers who do not pay, the commissions payment will only be made

after the collection of an account He also hires two individuals to assemble the parts into

clocks ready to sell to retailers. In the following few days, he incurs $2,250 in labor costs for

assembly and determines that the average cost of the finished clocks represents 70% of the

average wholesale price he will utilize (40% parts and 30% labor). Since the assembly labor is

paid hourly (at the end of the month), Gary will include this cost as a part of the Cost of Goods

Sold. The balance sheet on January 18 includes the wages payable but not the salaries of the

secretary and salesperson since they represent a "fixed" cost paid at the end of the month.

The assembly wages are recognized as a liability since they have been incurred and represent

the additional value added to $3,000 of inventories converted to finished goods but not yet paid

for.

Entries

Finished Goods

Wages Payable

+2,250

+2,250

Finished Goods

Materials

+3,000

- 3,000

Assets

Cash

Inventories

Materials

Finished Goods

Total Current Assets

Deposits

Organizational Costs

Accum. Amortization

Net Organizational Costs

Total Assets

Liabilities & Equity

Wages Payable

Total Current Liabilities

39,800

5,000

5,250

50,050

(8,000-3,000)

(0+2,250+3,000)

1,300

900

( 0)

900

52,250

2,250

2,250

Common Equity

Retained Earnings

Total Equity

50,000

( 0)

50,000

Total Liab. & Equity

52,250

8

(0+2,250)

Many firms simply include the wage component as a part of the Income Statement

under the category of Wages & Salaries. Strictly speaking, however, it is a part of the Cost of

Goods Sold, just as it would be included in the purchase price were the clocks to have been

purchased already assembled. Including the assembly wages as a part of the Cost of Goods

Sold, a direct cost, is very useful for managerial purposes. Specifically, it helps in distinguishing

those costs that are fixed costs from those that are variable costs.

January 21, 2002

The salesperson reports that an order for $5,000 has been placed by a contact that was

made and who provided references for purchasing on credit terms of net 30. At this point, the

income statement begins to reflect the transactions as well as the balance sheet:

Entries

Revenues

Accounts Receivable

+5,000

+5,000

Finished Goods

Cost of Goods Sold

- 3,500

+3,500 (results in a decrease in retained earnings)

Commissions Payable

Commission Expense

+ 500

+ 500

(results in a decrease in retained earnings)

Taxes Payable

Tax Expense

+ 200

+ 200

(results in a decrease in retained earnings)

(results in an increase in retained earnings)

Revenues

Cost of Goods Sold

Gross Profit

5,000

3,500

1,500

(0+5,000)

(0+3,500)

General & Administrative Expense

Commissions

Amortization

Taxable Income

500

0

1,000

(0+500)

200

800

(0+200)

Taxes (20%)

Net Income

9

Assets

Cash

Accounts Receivable

Inventories

Materials

Finished Goods

Total Current Assets

Deposits

Organizational Costs

Accum. Amortization

Net Organizational Costs

Total Assets

Liabilities & Equity

Wages Payable

Commissions Payable

Income Taxes Payable

Total Current Liab.

39,800

5,000

5,000

1,750

51,550

(0+5,000)

(5,250-3,500)

1,300

900

( 0)

900

53,750

2,250

500

200

2,950

(0+500)

(0+200)

Common Equity

Retained Earnings

Total Equity

50,000

800

50,800

(0+800)

Total Liab. & Equity

53,750

10

January 22-31, 2002

During the ensuing ten days, the following transactions occur:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

An additional $15,000 of parts are purchased for cash

$16,000 of parts are assembled into finished clocks with labor costs of $12,000

Sales of $30,000 are made on credit of net 30

All employees are paid on the 31st of the month

Utility bills totalling $750 arrive on the 30th and are due by the 15th of February

Rent is paid

Amortization of Organizational Costs is recognized (straight-line over 15 years or 180

months)

Entries

Cash

Materials

- 15,000

+15,000

Materials

Finished Goods

- 16,000

+16,000

Wages Payable

Finished Goods

+12,000

+12,000

Revenues

Accounts Receivable

+30,000

+30,000

Finished Goods

Cost of Goods Sold

- 21,000

+21,000

Commissions Payable

Commission Expense

+ 3,000

+ 3,000

Wages Payable

Cash

- 14,250

- 14,250

Salaries

Cash

+ 2,700

- 2,700

Utilities Payable

Utility Expense

+

+

Rent Expense

Cash

+ 2,500

- 2,500

Amortization Expense

Accumulated Amortization

+

+

(Secretary 1,500 plus salesman base 1,200)

750

750

5

5

11

The January income statement and January 31 balance sheet appear as follows:

Revenues

Cost of Goods Sold

35,000

24,500

Gross Profit

10,500

General & Administrative Expense

Commissions

Salaries

Rent

Utilities

Amortization

Taxable Income

3,500

2,700

2,500

750

5

1,045

Taxes (20%)

209

Net Income

836

Assets

Cash

Accounts Receivable

Inventories

Materials

Finished Goods

Total Current Assets

Deposits

Organizational Costs

Accum. Amortization

Net Organizational Costs

Total Assets

Liabilities & Equity

Wages Payable

Utilities Payable

Commissions Payable

Income Taxes Payable

Total Current Liab.

(5,000+30,000)

(3,500+21,000)

(500+3,000)

(0+2,700)

(0+2,500)

(0+750)

(0+5)

5,350

35,000

(39,800-15,000-14,250-2,700-2,500)

(5,000+30,000)

4,000

8,750

53,100

(5,000+15,000-16,000)

(1,750+16,000+12,000-21,000)

1,300

900

( 5)

(0+5)

895

55,295

0

750

3,500

209

4,459

Common Equity

Retained Earnings

Total Equity

50,000

836

50,836

Total Liab. & Equity

55,295

12

(2,250+12,000-14,250)

(0+750)

(500+3,000)

(Cumulative from Income Stmt)

(Cumulative from Income Stmt)

Statement of Cash Flows

The Statement of Cash Flows reconciles the difference between accrual accounting

figures and the actual inflows and outflows of cash. From a financial perspective, the relevant

figures for investment and valuation purposes is the cash flows generated by a firm since

accounting profits are more conceptual in nature.

Creating the January Statement of Cash Flows for Gary's company is relatively simple

due to the fact that the beginning balance sheet (i.e., prior to inception of the firm) consisted of

all zeroes. The statement itself is comprised of three sections representing the sources and

uses of cash to the firm. The first section, From Operating Activities, considers the net income

of the firm during the period and adds back the non-cash expenses such as amortization and

depreciation. Included in this section are changes in working capital accounts (current assets

and current liabilities) other than the cash account since these accounts are most directly

related to the day-to-day operations of the company. The From Investment Activities section is

looking at the investment in, or disposal of (disinvestment), those assets that are more related

to the long-term ongoing operations of the firm. The section From Financing Activities

considers the sources of long-term (permanent) financing of the company.

When calculating the cash flow resulting from a change in a balance sheet item, one

needs to keep in mind whether the balance sheet account is an asset account or a

liability/equity account. (Contra-asset and contra-liability accounts are really on the "wrong"

side of the balance sheet but are listed in such a manner as to associate them with the account

that is directly affected by them.) A source of funds is either a decrease in an asset account

from one period to the next (such as selling off some inventories) or an increase in a

liability/equity account (such as borrowing money from a bank). A source of funds will appear

as a positive number on the Statement of Cash Flows. A use of funds is just the opposite: A

use of funds is either an increase in an asset account (such as buying inventories) or a

decrease in a liability/equity account (such as paying off some debt).

A special point should be made of the retained earnings account. From the relationship

noted above, the two factors affecting the change in retained earnings are the net income and

dividends paid. Since the net income is reflected in the From Operating Activities section, only

the dividend payments are considered when calculating the cash flows From Financing

Activities section. As the relationship between beginning retained earnings and ending retained

earnings indicates, and change that is not equal to the amount of net income must be a

consequence of cash dividends paid.

13

The January Statement of Cash Flows for Gary's company appears as:

From Operating Activities:

Net Income

Plus: Amortization

836

5

Operating Cash Flows

(From the Income Stmt)

(From the Income Stmt)

841

Changes in Working Capital

Accounts Receivable

Materials Inventories

Finished Goods

Utilities Payable

Commissions Payable

Income Taxes Payable

(35,000)

( 4,000)

( 8,750)

750

3,500

209

From Working Capital

(43,291)

Total From Operating Activities

(0 - 35,000)

(0 - 4,000)

(0 - 8,750)

( 750 - 0)

( 3,500 - 0)

( 209 - 0)

(42,450)

From Investing Activities:

Deposits

Organizational Costs

( 1,300)

( 900)

Total From Investing Activities

(0 - 1,300)

(0 900)

( 2,200)

From Financing Activities:

Equity

50,000

Total From Financing Activities

50,000

Total Cash Flows

5,350

Plus: Beginning Cash Balance

(50,000 - 0)

0

Ending Cash Balance

5,350

As indicated by the Ending Cash Balance figure of the Statement of Cash Flows, it is identical

to the cash balance determined on the balance sheet. Just as Total Assets can be compared

to Total Liabilities & Equity as a check figure when preparing proforma statements to ensure the

correctness in the modeling, the Ending Cash Balance figure from the Statement of Cash Flows

is a handy check figure as well.

14

February 1-28, 2002

Continuing the example of Gary's clock company for February, the transactions that

occurred are as follows:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

Sales of $80,000 were made on thirty days' credit.

A six-month bank loan of $10,000 was acquired at month-end and secured by

receivables.

Collection of receivables amounted to $42,000.

Commissions on the collected receivables were paid ($4,200).

Purchases of $53,000 of clock parts were made on thirty days' credit (now that a credit

history is being developed).

$36,000 of parts were assembled into clocks.

$27,000 of assembly wages were incurred and paid at month end.

The previous month's utility bills were paid and new billings of $1,150 arrived.

The two salaried employees were paid at the end of the month.

Due to a dispute over some minor finish-out work that the landlord had promised but

failed to make, rent was withheld by Gary and not paid for February. (Note: Bad move - this is illegal; but if you did it, this is how you would recognize it!)

Having used up most of his savings and not drawing a salary, Gary paid himself a

$5,000 dividend.

15

Entries

Revenues

Accounts Receivable

+80,000

+80,000

Finished Goods

Cost of Goods Sold

- 56,000

+56,000

Commissions Payable

Commission Expense

+ 8,000

+ 8,000

Cash

Bank Note

+10,000

+10,000

Cash

Accounts Receivable

+42,000

- 42,000

Cash

Commissions Payable

- 4,200

- 4,200

Materials

Accounts Payable

+53,000

+53,000

Materials

Finished Goods

- 36,000

+36,000

Wages Payable

Finished Goods

+27,000

+27,000

Cash

Wages Payable

- 27,000

- 27,000

Cash

Utilities Payable

-

Utilities Payable

Utility Expense

+ 1,150

+ 1,150

Cash

Salary Expense

- 2,700

+ 2,700

Rent Expense

Rent Payable

+ 2,500

+ 2,500

Cash

Retained Earnings

- 5,000

- 5,000

Amortization Expense

Accumulated Amortization

+

+

750

750

5

5

16

The February Income Statement would look as follows:

Revenues

Cost of Goods Sold

80,000

56,000

Gross Profit

24,000

General & Administrative Expense

Commissions

Salaries

Rent

Utilities

Amortization

8,000

2,700

2,500

1,150

5

Taxable Income

9,645

Taxes (20%)

1,929

Net Income

7,716

17

(0+80,000)

(0+56,000)

(0+8,000)

(0+2,700)

(0+2,500)

(0+1,150)

(0+5)

(0+1,929)

The February 28 Balance Sheet is:

Assets

Cash

17,700

Accounts Receivable

Inventories

Materials

Finished Goods

Total Current Assets

Deposits

Organizational Costs

Accum. Amortization

Net Organizational Costs

Total Assets

73,000

21,000

15,750

127,450

(5,350+10,000+42,000-4,200

-27,000-750-2,700-5,000)

(35,000+80,000-42,000)

(4,000+53,000-36,000)

(8,750-56,000+36,000+27,000)

1,300

900

( 10)

(5+5)

890

129,640

Liabilities & Equity

Wages Payable

Accounts Payable

Utilities Payable

Rent Payable

Commissions Payable

Income Taxes Payable

Bank Loan

Total Current Liab.

0

53,000

1,150

2,500

7,300

2,138

10,000

76,088

Common Equity

Retained Earnings

Total Equity

50,000

3,552

53,552

Total Liab. & Equity

129,640

18

(0+27,000-27,000)

(0+53,000)

(750-750+1,150)

(0+2,500)

(3500+8,000-4,200

(209+1,929)

(0+10,000)

(836+7,716-5,000)

The Statement of Cash Flows that results for February is

From Operating Activities:

Net Income

Plus: Amortization

Operating Cash Flows

Changes in Working Capital

Accounts Receivable

Materials Inventories

Finished Goods

Accounts Payable

Utilities Payable

Rent Payable

Commissions Payable

Income Taxes Payable

From Working Capital

Total From Operating Activities

7,716

5

7,721

(38,000)

(17,000)

( 7,000)

53,000

400

2,500

3,800

1,929

( 371)

(From the Income Stmt)

(From the Income Stmt)

(35,000 - 73,000)

( 4,000 - 21,000)

( 8,750 - 15,750)

(53,000 0)

( 1,150 - 750)

( 2,500 0)

( 7,300 - 3,500)

( 2,138 - 209)

7,350

From Investing Activities:

Total From Investing Activities

0

From Financing Activities:

Bank Loan Payable

Dividends Paid

10,000

( 5,000)

Total From Financing Activities

5,000

Total Cash Flows

12,350

Plus: Beginning Cash Balance

Ending Cash Balance

5,350

17,700

19

(10,000 - 0)

(836 + 7,716 - 3,552)