File - MTI News Writing

advertisement

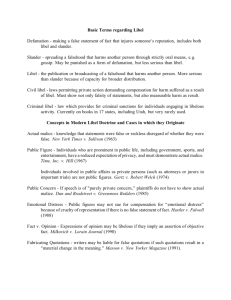

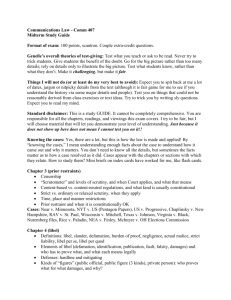

Chapter 7 Summary & Terms • Freedom of the press is ensured by wording in the First Amendment. Journalists constantly fight to protect their rights under the Constitution against those who wish to restrict the free flow of information. A journalist’s rights fall into two main categories: (1) privileges and protections for journalistic activities and (2) access to government operations and records. Privileges for journalists include fair report privilege, opinion privilege and fair comment and criticism. All privileges apply after the material is printed or published. The notes journalists take and the sources they use are protected by the federal Privacy Protection Act and, in 31 states, by shield laws. Freedom of information gives the public the right to know what government is doing. Journalists, as representatives of the public, have access to courtrooms, to meetings of governmental agencies and other public bodies and to governmental records, but exceptions and “gray areas” exist in all three of these categories. Reporters should not be intimidated by public officials denying them access to records or meetings. They should remind bureaucrats that the public, which reporters represent, is paying their salaries. If they can’t get past the bureaucrats, they should find another way to get the information. Online resources offer reporters information and advice on the FOIA, relevant state laws and press-rights questions. Examples are the Web sites of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and the Student Press Law Center. Reporters can get in trouble if they are not familiar with the laws and ethics governing their profession. o They can be jailed for contempt of court, trespassing and sedition. o They can be sued for libel, invasion of privacy and breach of contract. o They can be fired for plagiarism, fabrication and lapses in ethics. o They can receive angry phone calls for bias, bad taste and blunders and bloopers. Libel is the publication of a false statement that maliciously or carelessly damages someone’s reputation. To avoid libel, reporters must be sure of their facts. They must be able to prove that a statement is true. Attribution is not enough to protect a journalist. The beginning reporter’s guide to libel includes: o Any living person or small group can bring a libel suit. Dead people and the government cannot. o Usually, the publication is sued, but the reporter and editors can be defendants, too. o The essential elements of libel are: The statement must be (1) false, (2) defamatory and (3) published – either printed, broadcast or posted on the Internet; (4) plaintiff must be identified – either named, described or pictured; and (5) defendant must be at fault, through negligence or malice. o The best defenses are truth, consent of the subject and fair report privilege. o Tips for avoiding libel include verifying questionable material, giving people a chance to defend themselves against accusations and not printing claims or Chapter 7 Summary & Terms unofficial charges. If a mistake is made, the reporter should check with the editor and the paper’s attorney and run a correction or retraction immediately. o Reporters should not allow the threat of a libel suit to keep them from printing the truth. Public officials and public figures must prove that the publication acted with “actual malice” to win libel suits. “Actual malice” is recklessly disregarding the truth or knowingly publishing lies. Common words that can lead to libel litigation range from “adultery” to “unprofessional.” Five landmark Supreme Court cases that helped shape libel law are: o New York Times v. Sullivan. Set the precedent that any public official suing for libel must prove that damage was done with “actual malice.” o AP v. Walker and Curtis Publishing v. Butts. Extended Sullivan by ruling that the “actual malice” requirement applies to well-known public figures. o Gertz v. Welch. Set the precedent that ordinary folks need show only that a defamation resulted from negligence, not actual malice. o Hutchinson v. Proxmire. Ruled that press releases and newsletters of public officials are not protected from libel suits. Invasion-of-privacy cases challenge journalistic ethics and judgment. The four common ways to invade someone’s privacy are intrusion, public disclosure of private facts, false light (portraying someone inaccurately), and appropriation. Copyright protects all forms of creative expression. It legally establishes who owns a creative work and who controls its sale and reproduction. Copyright law protects reporters from theft and keeps them from stealing others’ work. Stories are automatically copyrighted as soon as they appear in the paper or online. Journalists who plagiarize can be fired, sued and forced to pay damages. To reprint an excerpt from someone else’s work, obtain permission from the author or publisher. Notify the person, in writing, of your intent. Journalists are legally allowed “fair use” of copyrighted material when something is newsworthy and the writer needs to show readers what makes it so by reprinting images or excerpts. Under fair use, journalists can reprint only a small amount of material, must not diminish the value of the original work, and must always credit the source of the material. Parodies are OK as long as journalists use them as a springboard for their witty ideas and clever comments, adding new material for comic effect. Businesses register their names and logos as trademarks to prevent them from being stolen. Trademarked names, such as Jello-O, Band-Aid and Realtor, should not be used in a generic way. Logos are the distinctive designs companies stamp on their products. Publishing restrictions imposed from outside the newsroom are called censorship. Publishing restrictions imposed from inside the newsroom are called self-censorship. Five reasons why a story might get spiked are vulgar language, offensive topic, conflict of interest, legal/ethical issues, and reporting flaws. While U.S. newspapers are free from virtually all forms of outside censorship, student publications face censorship regularly. Chapter 7 Summary & Terms Prior review is a policy that allows or requires advisers or school administrators to approve or censor stories in advance of publication. In public colleges, student editors are entitled to control the content of campus publications. School officials cannot fire editors or advisers, discipline reporters, confiscate publications, withhold funding or make other attempts to censor or manipulate content. The U.S. Supreme Court issued the following two decisions about the limits on First Amendment freedoms in public high schools: o Tinker v. Des Moines School District (1969). Free expression must be allowed, provided it doesn’t disrupt school discipline or invade the rights of others. o Hazelwood School District v. Kuchmeier (1988). Censorship is allowed, but extracurricular publications enjoy greater freedom than a classroom activity. In private colleges and high schools, the school administration is entitled to act like any other publisher in controlling what’s printed, although some state laws provide extra free speech protection. Journalism’s seven deadly sins are: o Deception: Lying or misrepresenting oneself to obtain information. (A few exceptions exist, such as undercover reporting.) o Conflict of interest: Accepting gifts or favors from sources or promoting social and political causes. o Bias: Slanting a story by manipulating facts to sway readers’ opinions. o Fabrication: Manufacturing quotes or imaginary sources, or writing anything known to be untrue. o Theft: Obtaining information unlawfully or without a source’s permission. o Burning a source: Deceiving or betraying the confidence of someone who provides information for a story. o Plagiarism: Passing off someone else’s words or ideas as one’s own. Jayson Blair committed journalistic fraud, including plagiarism, in dozens of stories for The New York Times. He resigned in shame in 2003. All journalists should adhere to a code of ethics, standards and values that guide their professional conduct. Journalists began writing codes of ethics in the late 1800s. Most journalists now abide by the Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics, written in 1996. When facing ethical dilemmas, journalists should ask: What purpose does it serve to print this? Who gains? Who loses? Is it worth it? What best serves the readers? Doing what’s safe or legal or least likely to cause trouble isn’t the same as doing what’s right. Sixty-two percent of Americans say they don’t trust the press; only 21 percent rate the honesty and ethical standards of newspaper reporters as “high” or “very high.” Out of 21 professions rated on those standards, newspaper reporters ranked 16th, behind car mechanics but above lawyers. Journalists are stuck with a negative image. Raising ethical standards may be the best way to change that. Actual malice: In libel, a situation in which a publication recklessly disregarded the truth or knowingly published lies; must be proved by public figures and public officials. Chapter 7 Summary & Terms AP v. Walker: A 1967 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that extended the Sullivan ruling by holding that the “actual malice” requirement applies to well-known public figures, not just governmental public officials. See also Curtis Publishing v. Butts. Appropriation: A form of invasion of privacy in which a publication uses someone’s name, photo or words without authorization to endorse or sell a product or service; usually happens more in the advertising department than the newsroom. Bad taste: Using words or ideas that some readers may find offensive. Bias: Taking sides in a story or failing to present both sides of an issue fairly; slanting a story by manipulating facts to sway readers’ opinions. Blair, Jayson: Resigned in shame from The New York Times in 2003 after he admitted that he lied, plagiarized stories and deceived editors. Breach of contract: Publishing the name of a confidential source after promising not to do so. Burning a source: Deceiving or betraying the confidence of someone who provides information for a story. Censorship: Publishing restrictions imposed from outside the newsroom. Code of ethics: A set of ethical guidelines for journalists to follow. Conflict of interest: Accepting gifts or favors from sources or promoting social and political causes. Consent: A defense against libel. If a person allows a reporter to publish a defamatory statement, that person can’t sue for libel later. Contempt of court: An offense that a reporter can be charged with if the reporter refuses to tell a judge the source of controversial material used in a story. Copyright: Government-approved protection for all forms of creative expression. It establishes who owns a creative work and prevents thieves and plagiarists from stealing work and publishing it elsewhere. Curtis Publishing v. Butts: A 1967 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that extended the Sullivan ruling by holding that the “actual malice” requirement applies to well-known public figures, not just governmental public officials. See also AP v. Walker. Deception: Lying or misrepresenting oneself to obtain information. Ethics: Standards and values that guide journalists’ professional conduct. Fabrication: Manufacturing or falsifying any facts, quotes or events for a story. Fair comment and criticism: The privilege that allows reporters to criticize performers, politicians and matters of public interest. Fair report privilege: Allows journalists to report anything said in official government proceedings, no matter how slanderous or defamatory the quotes might be, without being sued or censored as long as the information is reported accurately and fairly. Fair use of copyrighted material: A legal concept by which journalists are allowed to use a small amount of copyrighted material if the material is newsworthy, as long as the value of the work isn’t diminished and they give credit to the source. False light: A form of invasion of privacy in which a newspaper publishes a story, headline or cutline that portrays someone in an inaccurate way. First Amendment: The amendment to the U.S. Constitution that protects five freedoms – press, speech, religion, assembly and petition. Freedom of information: The public’s right to monitor what its government is doing – “the right to know.” Chapter 7 Summary & Terms Freedom of Information Act: Federal legislation passed in 1966 requiring that all federal agencies make most of their records available upon request. Each state has it’s own version of the FOIA. Gertz v. Welch: A 1973 U.S. Supreme Court case that established that ordinary folks, to win a libel suit, need to show only that a defamation resulted from negligence, not actual malice. Hazelwood School District v. Kuchmeier: A 1988 U.S. Supreme Court decision that established the right of school administrators to censor high school publications. A publication in which the school has given students the authority to edit content enjoys greater freedom than a classroom activity. Hutchinson v. Proxmire: A 1975 U.S. Supreme Court decision that established that press releases and newsletters of public officials are not protected from libel suits. Intimate: Something personal that people wouldn’t ordinarily want revealed. Intrusion: A form of invasion of privacy in which a reporter gathers information unethically in a situation where someone has a right to expect privacy; might involve trespassing, secret surveillance or misrepresentation. Invasion of privacy: Using people in a story in a way that violates their right to be left alone. Lapse in ethics: Any behavior by reporters, whether on or off the job, that could damage the publication’s reputation. Liable: To be legally responsible or obligated. Libel: Publication of a false statement that maliciously or carelessly damages someone’s reputation. Logos: Distinctive designs that companies stamp on their signs and products. Misrepresentation: Disguising oneself to gain unauthorized access to a private area. Negligence: In libel, a reporter’s failure to exercise appropriate care in a story. New York Times v. Sullivan: Landmark libel case in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that public officials suing for libel must prove that the damage was done with “actual malice.” Offensive: Liable to humiliate someone if the information became widely known. Open-meeting laws (or “sunshine” laws): Legislation requiring local, state and federal governmental bodies that receive revenue from taxes to open most of their sessions to the public and notify the media in advance of all meetings. Opinion: An idea that doesn’t claim to be factual and cannot be false. Opinion privilege: Protects written opinions from libel suits. Plagiarism: Passing off the words or ideas of others as one’s own, without attribution. Prior review: A policy that allows or requires college advisers or administrators to approve or censor stories in advance of publication. Privacy Protection Act: Protects newsrooms from searches and seizures unless officials suspect someone in the newsroom is involved with a crime, is planning to destroy evidence or is about to be hurt. Private: Known only to family or friends and not a legitimate concern to the public. Privilege: A common legal term used to describe benefits enjoyed by a specific group, such as journalists. Public disclosure of private facts: A form of invasion of privacy in which a reporter reveals personal details (e.g., about someone’s sex life or medical history) that are private, intimate or offensive. Public figure: A person who has acquired fame or notoriety, such as a performer or athlete, or has participated in some public controversy, such as a protester or social activist. Chapter 7 Summary & Terms Public official: Someone who exercises power or influence in governmental affairs, such as a police officer, mayor or school superintendent. Secret surveillance: Using hidden cameras, recorders or bugging devices. Sedition: The publication of material considered too critical of government leaders or policies; no longer an offense in the United States. Self-censorship: Publishing restrictions that originate within the newsroom; also referred to as “conforming to community values” or “meeting our editing standards.” Shield laws: Legislation that protects reporters by preserving the confidentiality of their notes and sources; enacted by 31 states. Slander: Defamation by spoken word. Theft: Obtaining information unlawfully or without a source’s permission. Tinker v. Des Moines School District: A 1969 U.S. Supreme Court decision that allows free expression by high school students or teachers in speech or print as long as it doesn’t disrupt school discipline or invade the rights of others. Trademarks: Business names and logos that are registered with the federal government to prevent them from being stolen. Trespassing: A crime in which a reporter walks or snoops on private property without the owner’s consent. Truth: The best defense against libel. If reporters can prove their stories are true, they cannot lose a libel suit. Vulgar language: Profanities that editors often delete from stories to avoid offending readers.