Chapter Three: Cultural projects and organizations for Youth Culture

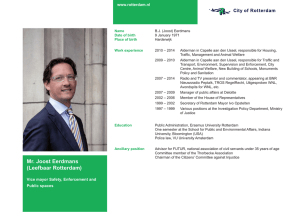

advertisement