Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer

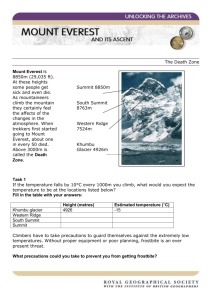

advertisement