6th Grade STM Unit - Research 2

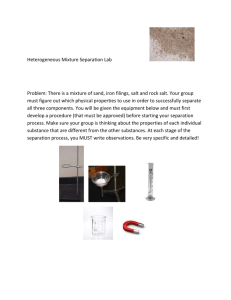

advertisement