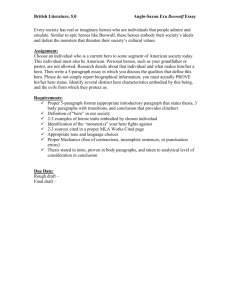

Point of Analysis

advertisement