preventing military interventions

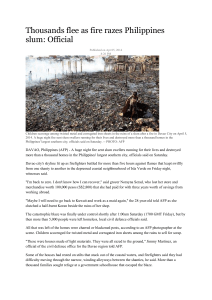

advertisement