Week 2 – the marketing environment

advertisement

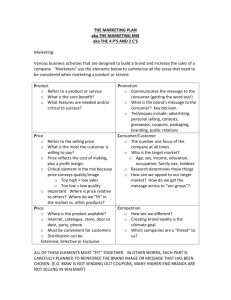

Table of Contents Week 1 ................................................................................................................. 7 On value creation .............................................................................................................................................. 7 Managing relationships .................................................................................................................................. 7 Week 2 – the marketing environment ................................................................... 8 Week 2 – From the reading ................................................................................. 10 Identifying the competitive advantage ................................................................................................. 11 Managing the product line: new product development, product life cycle, extension strategies ........................................................................................................................................................... 12 Porter’s model of industry/market evolution ................................................................................... 13 The experience curve ................................................................................................................................... 14 The product life cycle portfolio matrix: ................................................................................................ 14 Week 3 – Researching the consumer ................................................................... 15 Assess based on the cultural, social, personal and psychological factors .............................. 15 The buying decisions process ................................................................................................................... 15 Consumer theory ........................................................................................................................................... 16 Veblen, Thorstein (1899) The Theory of the Leisure Class, Boston, Houghton Mifflin ...... 16 From the reading (of week 3) .............................................................................. 16 Online communities...................................................................................................................................... 16 The virtual brand community: ................................................................................................................. 17 Loyalty, loyalty schemes and consumer privacy: ............................................................................. 17 Loyalty schemes ............................................................................................................................................. 17 Consumer privacy.......................................................................................................................................... 17 Conspicuous consumption and the new consumer ......................................................................... 18 An evaluation of the evolving literature............................................................................................... 18 Antecedents of conspicuousness............................................................................................................. 18 Uniqueness ....................................................................................................................................................... 19 Social conformity ........................................................................................................................................... 19 the White House started asking us why the private sector wasn’t kicking in. We didn’t have an answer. We weren’t business leaders, but that was not the right reply. And we had another challenge—telling the story of extreme poverty and making people care about ending it. (RED) took shape from these related challenges. (RED) would face the typical challenges of a start-up enterprise, from brand positioning and inadequate capital to organizational development and international expansion. In addition, its unique origin was reflected in a novel business model. had to make sure the products were compelling and that they sold. To be sustainable, our partner companies had to make money. To keep (RED) vibrant for the long haul, it a)had to be good for the Global Fund and b)profitable for the businesses involved. “Each launch partner had at least one committed champion,” -- “Tamsin at Gap, John Hayes at American Express, Dave Maddocks at Converse, Robert Triefus and Wanda McDaniel at Armani. No company joined (RED) through CEO edict. In short, building the brand and making fast money to save lives were inseparable but sometimes opposing goals BACKGROUND: This basic concept, selling consumer products that were desirable in their own right to generate revenue for a prosocial idea, would be tweaked and used again in creating (RED) Following the case of a very special christmas Seeing the need for a permanent lobbying organization devoted to generating awareness and building ongoing bipartisan support, Shriver and Bono worked for two years to finance and cofound “Debt, AIDS, Trade, Africa,” or DATA, in 2002 In 2005, DATA was a founding member of the ONE Campaign to make poverty history, an outgrowth of Bono and Shriver’s efforts. AIDS in Africa 33 million people with aids more than 4000 dies on a daily basis in africa With several billion dollars from governments around the world, the Global Fund began moving people in Africa onto ARVs, but the organization, which had been established as a publicprivate partnership, had raised only $5 million in three years of private-sector engagement. Bono and Shriver had lobbied the American government to capitalize the Global Fund. Soon after, Bush administration officials started inquiring as to when the private sector was going to take a seat at the table. With this pressure building, the two began brainstorming ways to engage the power of the business community and the vast number of people who were not committed activists but who, Bono and Shriver believed, would want to help if “the ask” was simple They remembered the lesson of the Very Special Christmas albums: Selling something people are excited to buy feels better to both sides than hawking raffle tickets or token charity wares Product RED Former cabinet official of the Clinton administration advised them to be like nike. Iconic brands create real impact - were able to generate emotional impact by being in malls, posters , TV and generally part of everyday life A brand that would be trusted and valued by customers RED because it was the color of emergency We call the parentheses or brackets the “embrace.” Each company that becomes (RED) places their logo in the embrace. And this embrace is elevated in superscript to the power of RED. Thus the name: (PRODUCT)RED. Smith explained: “We couldn’t be like the Nikes of the world in terms of size and spending, but we thought we could excite these companies to think like us—to become moved by the idea of helping eliminate AIDS in Africa. We also wanted to do the same with shoppers, to make consumers feel the impact of the same embrace: (YOU) RED.” The Business model Didn’t just want simply to infiltrate their marketing budgets. We wanted the partners to do what they do best—design, market, and promote cool stuff. Our role was to add something more—the association with the (RED) movement.” Partner companies made a multiyear commitment and Were given category exclusivity over that period and the right to design and sell (RED)themed products (RED) products did not necessarily have to be colored red Each partner was responsible for marketing its own (RED)-branded products, using funds intended for existing marketing campaigns This meant that (RED) itself did not incur the promotional costs typically associated with new product launches 50% of the profits went to the product red Building Partnerships In the fall of 2004, Bono met with CEO Ken Chenault and CMO John Hayes of American Express. The gains for AE: capitalize on the growing trend of conscious consumerism allow their company to reach new demographics. Bono and Shriver saw American Express as an ideal launch partner The partnership would generate a lot of money. Second, they were a global brand with worldwide recognition. Third we knew that we’d get instant credibility from a serious, buttoned-up company. After the meeting, the parties started negotiating an agreement for a (RED) American Express card. Other partners were: Gap, Converse, and Giorgio Armani etc. (RED) chief operating officer Colin Brady (HBS class of 2004) recalled: “(RED) targeted brands with special emotional relationships with their consumers. It was important that the (RED) message be something people would wear or display proudly.” The team approached other companies who declined to “take the risk” of an association with AIDS and Africa. Among the explanations given were: Africa is too far away, consumers don’t care, the issue is too complicated and poorly understood, and AIDS is too controversial. (RED) worked with each partner The idea was to create a collaborative relationship --> Getting involved without getting in the way of the people who really knew what they were doing. The (RED) product had to be communicated differently from their other products because it had to feel (RED), it had to be (RED), it had to capture our brand essence Partnering with these companies because they had competence in areas that we did not Get them to do what they did best Partner Benefits Shriver said: The profitability piece of this scared some partners in the beginning. They were used to the old charity model—they wanted to do a single T-shirt and donate 100% of the proceeds. But we said no, we wanted more robust collections and we didn’t want all the money, we wanted them to make money, too, because we knew that if they didn’t make money, the idea wasn’t sustainable. This felt odd—even bad—to them at first, but we wanted them to view us as business partners, not grantees. However: Partner companies faced a great deal of uncertainty in their decisions to sign on to the brand. Each company would be associating its brand with a potentially controversial new way of tackling an emergency, and doing so in a way that might invite confusion, scrutiny, and possible accusations of opportunism Launching (PRODUCT) RED Bono, Shriver, and the launch partners announced the (PRODUCT) RED initiative to the world at the annual World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, Switzerland in January 2006. By spring 2006, (RED) had done a soft launch with a limited product range in the United Kingdom. The official global launch of the campaign followed in October 2006, in the United States Action by each partner can be found on page 6 - pay special attention to the detail from each partner Promoting the (RED) Campaign The launch of (RED) was accompanied by a multimedia promotional blitz. Shriver and Bono made appearances on CNN’s Larry King Live talk show, Fox News, NBC Nightly News, and various other media outlets. The independence - half the revenues of the issues went to the Global Fund - 2 more issues followed - interview by Bono - featured politicians such as Tony Blair and Gordon Brown MySpace - Rare message invitation from the founder Tom Anderson VH1 - Creating emotions by presenting random people reading it alongside a soundtrack playing in the background Oprah - Bono and Oprah went on a shopping spree in Chigaco. Kanye West etc and other celebrities followed --> “This is the most important T-shirt I’ve worn in my life,” said Oprah, commenting on the Gap 100% African shirt she wore during the broadcast. The photos were taken by renowned photographer Annie Leibovitz and were featured on billboards into the Lincoln Tunnel, on every back page of the New York Times and throughout the pages of the New Yorker magazine. --> Creating iconic images Our partner companies not only knew how to do it well, they had the funds to do it big. They used money and talent that they had already allocated to their advertising budgets—the only difference was that now they used it to promote (RED) products. Initial Results While governments had donated over $4.8 billion to the Global Fund during its first few years of existence, corporations had contributed less than $5 million prior to the launch of (RED). But by January 2007, just three and a half months after launch, (RED)’s partners had contributed $25 million to the Global Fund. It was more than Denmark or China had given to the Global Fund the previous year. Historically, governments and civil organizations have carried the water on funding and administering public health programs, which is appropriate and critically necessary. However, too few regular people out there really felt connected to what their taxes or donations were supporting. (RED) opens the window and lets them in to see and feel and directly participate in the incredible challenge of eradicating a treatable, preventable disease. - 50 million USD generated in particular by October 2007 - note the upscaling increase within the few months Increasing awareness in the US - We did a pre-study before we launched in fall 2006 and had 1% awareness. We went back in the field in January 2007, and did another test. We found that, in the general population, we’d risen to 17% accurate awareness of the brand—17% of the public knew that (RED) was about AIDS in Africa. In our core demographic, that percentage was at 32%. Managing Misconceptions The most widespread misconception about (RED) was that it was a traditional charity However: (RED) saw itself as offering benefits back to its partner companies; as a result, (RED) had therefore intentionally approached the marketing divisions—not the foundation divisions—of possible partners Additionally, “charity” products tended to have a price markup which meant the donation fell exclusively on the consumer, not the company. (RED) products did not follow this model; the companies themselves covered the donation from their profits It aimed not to make people feel responsible for or guilty about world problems in order to induce them to buy, but instead to tap into their consumerism by offering them a (RED) choice Criticisms: Another critic agreed: “There is a broadening concern that business is taking on the patina of philanthropic activity and even substituting for it. It benefits the for profit partners much more than the charitable causes.” Buylesscrap.com, specifically attacked (RED)’s marketing practices and encouraged readers to donate directly to charitable causes. The site’s founder, who ran his own cause-marketing firm, wrote: “The (RED) campaign proposes consumption as the cure to the world’s evils. Can’t we just focus on the real solution—giving money?” Advertising Age published a critical article contrasting the collective marketing outlay by Gap, Apple, and Motorola on (RED)-related products—which the publication estimated to be as high as $100 million—to the “meager” amount donated to the Global Fund itself, which it estimated to be about $18 million. Exploring Possibilities: By the end of 2007, (RED) had contributed $50 million to the Global Fund, enough to put over 30,000 patients on ARV therapy and institute a variety of other health initiatives in Swaziland and Rwanda. To help keep pace with (RED)’s growth, the company had recently hired advertising and communications expert Susan Ellis Smith from Omnicom Group as CEO to help address several key issues in extending the brand: partnerships, customer relationship management, and, most critically, sustainability. Partnerships Because the (RED) model was reliant on partnerships, the team needed to think carefully about how to view its existing partner relationships going forward, how many partners it should have at any given time, and what types of new partners it should target. The team considered a wide range of options, from consumer-packaged goods to service brands and even music content. Brady noted: We need to figure out how people can give something—even $1— every day. That’s why convincing people to give a portion of their utility bills to (RED) might be great. Customer Relationship Management “(RED)’s shareholders,” the people who were alive thanks to (RED) consumers “Making that connection is a critical part of completing the value circle,” she explained. “People want to know where the money is going and we need to show them, not only to say thank you but to encourage them to keep choosing (RED) over non-(RED) The team also considered how aggressively (RED) should try to convince consumers who bought one (RED) product to buy other kinds of (RED) products. Shriver noted: give them all an affinity card? create a loyalty programand try to motivate them to buy everything (RED)? Do we havean online (RED) store to make shopping (RED) easier or more exciting? Sustainability (RED) team needed to guarantee a constant revenue stream to the Global Fund We need to be smart about choosing our partners because we depend on them to create the cool products that will keep our brand fresh and relevant to consumers. At the same time, we have to think about fatigue, too. If we push this brand too hard, there’s a chance that consumers will become tired of our message and we’ll lose our relevance and our impact. Susan Ellis, (RED)’s new CEO, summed up her vision for the brand: I see (RED) as four things: commerce, community, education, and hope. Now we have to expand the model and continue to keep the (RED) brand dynamic. Given the support we have received from the (RED) community, given the power of the message, I am certain we will make (RED) a part of everyday life. Week 1 On value creation It appears that the organizations were pluralistic - Deliberate or emergent strategy? Hence the corporate strategy systemic according to Whittington (1993) Value in exchange = The value in products exchanged for money. However this type of value is not considered any more. The value comes from the consumer in interacting with the producer in co-creating a product. The value begins only when the consumer starts using the product. Hence value is not embedded in the products but generated by the consumers who use them. The notion that only customers can assess value to goods and services was expressed by Levitt (1983). According to Bendapudi and Leone (2003) co-production process gives the customers more credit than blame thus influences positively their perception and value creation process. According to the consumer culture theory (Arnould and Thompson 2005) Propositions: 1: Value is not delivered by a firm to customers but created in customer processes through support to those processes and through co-creation in interactions with customers. 2: The role of marketing is, on one hand, to develop and communicate value propositions to customers, and on the other hand, to support customers’ value creation through goods, services, information and other resources, as well as through interactions where co-creation of value can take place. Managing relationships Ryals (2005) indicates that this is not always the best strategy as it might cost more than benefit, when trying to retain customers. What is certain though is that not all the customers can be managed in relationships. Attempting to engage all the customers into a relation, can lead to inefficient and ineffective marketing behaviour. Finally, a firm can establish contacts with its customers, maintain, enhance and cultivate them; but also terminate them as well. From “satisfy the individual and the organizational goals” to “benefit the organization and its shareholders” and “value to customers”. The seller makes promises concerning for example physical goods, services, financial solutions, transfer of information, interactions and a range of future components. Communicating and delivering therefore is not enough. Relationships are necessary. Gronros discusses relationship marketing in general and Berry and Bitner service relationships, obviously their conclusions regarding the role of promises have to be the true fr any types of products in any context. The definition of promise was triggered by Calonius (1983) – The customers purchase based on promises of satisfaction (Levitt). In order to fulfil their promises, employees have to be concerned with customer focus, regardless their positions. The various systems in organizations have to facilitate and support the promises. Some marketing activities have to do with promise making while other have to do with promise keeping. According to Brown (2005) the marketing and sales department have a major role in making promises to the customers, whereas promise keeping is the role of others in the organization. However according to Ojasalo (1999) customers might have implicit, explicit and fuzzy expectations, hence it is not only the promises that must be kept but also the consumers’ expectations. Week 2 – the marketing environment PESTLE – MICROAUDITING SEE LECTURE NOTES Porter five forces analysis perhaps not very relevant in our case but can be used to recognize the potential enemies or limitations on product red by each one of the companies The BLUE OCEAN strategy is better though Ansoff's Product/Market Matrix This well known marketing tool was first published in the Harvard Business Review (1957) in an article called 'Strategies for Diversification'. It is used by marketers who have objectives for growth. Ansoff's matrix offers strategic choices to achieve the objectives. There are four main categories for selection. Market Penetration Here we market our existing products to our existing customers. This means increasing our revenue by, for example, promoting the product, repositioning the brand, and so on. However, the product is not altered and we do not seek any new customers. Market Development Here we market our existing product range in a new market. This means that the product remains the same, but it is marketed to a new audience. Exporting the product, or marketing it in a new region, are examples of market development. Product Development This is a new product to be marketed to our existing customers. Here we develop and innovate new product offerings to replace existing ones. Such products are then marketed to our existing customers. This often happens with the auto markets where existing models are updated or replaced and then marketed to existing customers. Diversification This is where we market completely new products to new customers. There are two types of diversification, namely related and unrelated diversification. Related diversification means that we remain in a market or industry with which we are familiar. For example, a soup manufacturer diversifies into cake manufacture (i.e. the food industry). Unrelated diversification is where we have no previous industry nor market experience. For example a soup manufacturer invests in the rail business. Ansoff's matrix is one of the most well know frameworks for deciding upon strategies for growth. Research is very important - •Make and sell --> Sense and respond •Original separation of research from Marketing Management •Now, research more integrated –long term planning more difficult –globalisation and consumers »(Malhotra and Peterson, Marketing Intellegence and Planning, Vol 19 (4), pp. 216-232) Types of research •Exploratory •Descriptive •Causal or predictive »(Brassington and Pettitt, 2000) Week 2 – From the reading Francis Aguilar’s system to scan information about the environment: 1) Undirected viewing (exposure without a specific purpose) 2) Conditioned viewing (Companies who were aware of some of they key factors and trends in their environment but did not undertake any search) 3) Informal search (Companies collected information for specific planning and decision making processes, but did so in informal and adhoc manner) 4) Formal search (The most highly developed formal practices – Collect specific information for specific purpose) – According to Jain by the 1980s many companies developed formal scanning system this process comes through the following a) Primitive: No purpose for scanning. Little discrimination between strategic and non-strategic information. b) Ad hoc: Certain sensitivity on information, especially if they were not examined before, but no planned or formal search. c) Reactive: Search is unstructured but specific information is collected especially on markets and competition. d) Proactive: Scanning structured and deliberate, using pre-established methologies with a view to predicting the environment for a desired future. Jain’s model can found on page 39 Assessing the impact of environmental threats: Kotler suggests that the planner can begin to make this assessment using opportunity and threat matrices. However the matrices can be oversimplified and sometimes some factors need to be assessed in combination to evaluate their cross impact. Criticizing SWOT Kotler suggested the following: Market leaders – largest market share (constantly innovate and protect weaknesses), Market Challenger – The companies that market leaders need to defend their position against (attacking the leader’s weaknesses. Many Japanese companies emerged this way), Market followers – Do not challenge for market leadership but for a variety of reasons prefer instead to follow the strategies of the market leader, Market nichers –Concentrate on specialist parts of the market which the larger companies have either consciously or unconsciously ignored – also called “concentrated marketing”. Appraising resources: Identifying the competitive advantage competences to customer needs) The concept of value chains: It was developed by Porter and aims to identify potential competitive advantages – 9 activities (five primary and four secondary) – Activities can be categorized and analyzed with a view to securing competitive advantage. Companies should analyze all their activities to see what each one contributes to the value the customer receives and the marginal costs in comparison to the competitor. Primary activities (associated with the input, throughput and output of goods and services in the organization)- consist of: Inbound logistics (delivery, stock control), Operations (packaging, assembly, equipment maintenance), Outbound logistics: (finished goods warehousing, material handling, order processing, delivery outwards), Marketing and sales (advertising, promotion, sales force, pricing and channels), Service (installation, repairs and parts supply) Support activities (comprise those activities which facilitate primary activities in the physical creation of the product and its sale and transfer to the buyer) – Procurement (purchasing inputs used in the organizations value chain such as information systems. Also procuring market research, accounting services etc), Technology development – support activities that improve product and process such as automation, communication with customers and so on, Human resource management (recruitment, selection, training and development), Firm infrastructure (systems of quality control, financial systems and marketing planning). Value chains extend outside the organizations through suppliers and distributors. Porter calls these as vertical linkages. Each of the primary and secondary activities are interdependent (horizontal linkages). This is also the basis for competitive advantage through optimization and coordination The benefits of the value chain: 1) It provides a framework for addressing our earlier problem of which attributes or activities to assess in our strengths and weaknesses analyses 2) Secondly it uses value and forces the analysis to see the strength and weaknesses in relation to the customers and the competition (Johnson and Scholes) observed this as well 3) The concept horizontal linkages re-enforces the concept of interrelationships and synergies and balance. 4) Vertical linkages make us think more broadly about strengths and weaknesses through suppliers and distributors The perspective to be taken should be from the market to the company and not from the company to the market. Profiling attributes through scales such as the likert one. The appraisal might be subjective, especially if its carried out by the managers of the company. In this cases a inter-functional team should be called, including consultants. Customers may give a good appraisal as well. According to Ferrell a SWOT analysis helps to foster collaboration and information exchange between the different functional areas of the business. In turn this can help create an environment of creativity and innovation. Hence, firms must: Match strengths and weaknesses to opportunities and threats, in order to be strategically fit Respond to environmental changes and trends, in other words the strategic windows – In a changing environment there are often only limited periods when the fit between the distinctive competences of a company and the opportunities presented by the environment at optimum positions – Abell named these as strategic windows. If SWOT does not exploit them right then these “windows” will close at a point in time. The concept applies for both the companies already in the market and new entrants. Prahalad and Hamel “core competence”-Is what can be used to develop successful strategies against competitors. Davidson - marketing assets are strengths that can be used to advance in the market place. For example Johnson & Johnson used its brand name to reposition in another niche of the market, and so did Mars as well. Managing the product line: new product development, product life cycle, extension strategies The planner must consciously seek to develop a portfolio of products to maintain long-run success. The four steps to achieve this are: 1) Identification of the current position of the company’s different products in their product life cycles – To do that Jain suggests that we have to acknowledge the sales growth pattern since introduction, any design and technical problems to be sorted, any sales and profit history of allied products, number of years the product has been on the market, casualty history of similar products in the past, extend to which additional sales efforts are necessary, assessing the easy or difficulty of acquiring dealers and distributors. 2) Analysis of the future sales and profit position of the products in their life cycles – This is difficult as life cycles can vary enormously, and there can be various possible shapes. The planner is required to forecast the sales and the profit. The product life cycle on profit lags the one on sales. 3) Analysis and implications of current and future forecast sales and profits curves “gap analysis” – Based on current and forecast profit life cycles compared to objectives for future profits there exists a gap between what is required and we forecast will be achieved. 4) Developing innovation and or extension strategies to fill the gaps between the life cycle and the objectives. Extension strategies are suggest under the table on page 81 week 2. This processes of extensions can be repeated by giving a series of enveloping curves, each one extending sales further. Criticisms and refinements of the basic product life cycle concept: No empirical evidence to support that the products follow a natural and preordained life cycle with the distinct stages outlined above. Critics include Dhalla and Yuspeh, and Levitt as well However Baker has recently proved the validity of the PLC – The S-shaped PLC exists but it cannot be consider as a universal law or a fact. Those who argue against the model are usually detracted from the usefulness of the concept to strategic marketing planning. O’Shaughnessy “ideal type” – An ideal type is used to compare with real examples to explain why the ideal type did not occur. The PLC as an ideal type is a standard against which to compare or predict real life cases. It can be viewed as heuristic device for explaining particular patterns of sales. The concept of industry market evolution Porter’s model of industry/market evolution Porter distinguishes between three stages of evolution of an industry/market: The emerging industry, the transition to maturity and the decline. - Emerging industry – Uncertainty prevails – On buyers: Product performance, potential applications, likelihood of obsolescence – Sellers: Customer needs, demand levels, technological developments/ Strategy must be shaped based on the following characteristics: Threat of entry, rivalry among competitors, pressure of substitutes, bargaining power of buyers and suppliers. - Transition to maturity: Falling industry profits, slow down in growth, customers knowledgeable about products and competitive offerings, less product innovation, competition in non-product aspects. Strategies focused on: Developing new market segments, focus strategies for specific segments, more efficient organization. The experience curve - - Decline: Competition from substitutes, changing customers’ needs, demographic and other macro-environmental forces and factors affecting markets. Strategies: Seek pockets of enduring demand, divest. The experience curve effect in strategic marketing planning It was observed by the Commander of the Wright Patterson Air Force Base in the U.S.A. The more time we repeat an activity the more proficient we become – In other words practice makes perfect BCG 1960 – The experience curve effect is observed to encompass all costs- capital, administrative, research and marketing – and to have transferred impact from technological displacements and product evolution. Resources to achieve it: 1) Increased labor efficiency 2) Greater specialization/redesign of working methods 3) Process and production improvements 3) Changes in the resources mix 5) Product standardization and product redesign Experience curve is expressed in percentages Strategic implications - By the time competitors are able enter the market, the early market leaded has established and unassailable cost advantage and competes on price leadership. The product life cycle portfolio matrix: It was developed by Barksdale and Harris the product life cycle portfolio and is specifically designed to deal with the criticisms of the BCG matrix. a) Ignores products that are new b) Overlooks markets with negative growth rate. However it has the same assumptions as the BCG: a) Products have finite life spans b) Strategic objectives and marketing strategy should match the market growth rate changes so as to take advantage of the challenges and opportunities as the product goes through the different stages c) For most mass produced products, costs of production are closely linked to experience – costs goes down as volume increases, d) Expenditures – Investment in plant and equipment and marketing expenses are directly related to growth. Products in growth markets will use more resources than products in mature markets. e) Products with high relative share of the market will be more profitable than products with low shares f) When maturity stage is reached, products with high market share generate a stream of cash greater than that needed to support them in the market. Warhorses: When the market comes to a negative growth cash cows become warhorses. Products with high market share and substantial generation of cash. This might take reduction of expenditure, or elimination of some models or segments from the market Dodos: Products with low shares of declining markets with little opportunity for growth or cash generation. Timing is crucial as they have to be removed from the portfolio however if the competitors already removed theirs, it might be profitable to stay. Infants: Products with high degree of risk, they do not immediately earn profits and consume substantial cash resources. Limitations: The developers claim that it is more comprehensive. The model is general and does not eliminate the problems regarding the products and markets in defining rates of growth. The benefits are based upon the inputs the company is based. Another model is PIMS (Profit Impact of Marketing Strategy) – See page 102-03 week 2 Recent developments: One of the most recent developments in the application of portfolio analysis tools which illustrates how these tools are continuously evolving to meet the needs of the contemporary marketer is the combination of portfolio analysis and the contemporary issue of “green marketing”. It was developed by Illinitch and Schaltegger through a three-dimensional matrix which is quantifying the environment impacts of business activities and comparing them with economic aspects of examined business. The horizontal plane of the matrix consists of the traditional BCGT matrix of growth against profitability with the quadrants retaining their respective metaphors. The size of the circle represents the size of the product or firm, in economic or environmental terms. The third vertical dimension measures environmental impact. The pollution units are calculated by multiplying toxic discharges by regulation standards weighting coefficients. Products deemed to be ecologically sound are called green and their counterparts are called dirty. Provides new opportunities – for example the case of “green dogs” on page 105 week 2. Chisnall suggest planning portfolio is here to stay as it can provide the following essential benefits to the management: 1) Generation of improved strategies because of the analysis involved in applying the portfolio techniques to a business. 2) A partial solution to the critical problem of resource allocation, and improving the different trade-offs between the various parts of the business. 3) These techniques offer a more scientific approach in the management process which is more rigorous and systematic than using intuition and hunch to make marketing decisions. Mercer suggests that portfolio-creating techniques are here to help in the decision making processes rather than to give definitive answers and substitute them. Week 3 – Researching the consumer Assess based on the cultural, social, personal and psychological factors The buying decisions process 1.Need recognition 2.Information search 3.Evaluation of alternatives 4.Purchase decision 5.Postpurchase behaviour Belk (1995) refers to this as the “new consumer behavior” – moves away from the traditional focuses on consumers as information processors to conceptualize consumers as socially connected beings. Consumer theory Consumer theory is a theory of microeconomics that relates preferences to consumer demand curves. The link between personal preferences, consumption, and the demand curve is one of the most complex relations in economics. Implicitly, economists assume that anything purchased will be consumed, unless the purchase is for a productive activity. Consumer/ consumption theory in marketing differs from the economic models of consumption Applicable in the developed world Extremes of consumer society: Conspicuous consumption Downshifting Veblen, Thorstein (1899) The Theory of the Leisure Class, Boston, Houghton Mifflin Leiss, W (1976) The Limits of satisfaction: An essay on the problem of needs and commodities. Toronto: University of Toronto Press: ◦Manipulation of consumers ◦Satisfaction of real needs Gervasi (cited in Baudrillard, 1998): ‘Choices are not made randomly. They are socially controlled, and reflect the cultural model from which they are produced. We neither produce nor consume just any product: the product must have some meaning in relation to a system of values’ }Brand communities }Oppositional brand loyalty }Aspirational groups/ Differentiation }Compensatory consumption (Woodruffe, 1997) }Construction of self within boundaries of society }Conspicuous innovator (McCracken, 1998) }Hedonistic consumption From the reading (of week 3) Online communities Marketing academics and practitioners have argued that the internet will transform marketing (Quelch and Klein, 1996; Hamill 1997) Promises of relationship marketing, one to one marketing and mass customization to be fulfilled (Cartellerieri et al 1997) Chairgouris 2000) The virtual brand community: Corporate attempts to instigate customer communities tend to be motivated more from a desire to provide easier company to customer 1-to-1 contact than to facilitate consumer to consumer (many to many contact). Such communities brought “death of distance” (Thomas 1999) – Muniz and O’ Guinn (2001) highlight how a strong brand community can be a threat to a marketer in the event of the community rejecting particular marketing activities or changes to a product. One unsatisfied customer can become thousands in a nano second. – Anti-brand communities (such in the case of Amway and “Boycott Nike” sites”. For example Yahoo! Chat rooms cover such topics as beer, wine, games, collecting and alternative medicines etc - Varies over demographic variables Offer opportunities to study specific target markets and provide insights to fragmented markets such as Yahoo! Chat room for African-American Teens. Loyalty, loyalty schemes and consumer privacy: There have been attempts to synthesize elements of previous approaches and provide conceptual frameworks (Dick and Basu 1994, Oliver 1999). The conative and affective elements of loyalty have been neglected although there are some exceptions to this (Oliver 1999, Hart 1999). However there may be many reasons for repeat patronage or repeat behaviour including lack of choice, habit, low income and convenience. Loyalty schemes All loyalty schemes offer some kind of reward to the customer. In most cases, the greater the degree of patronage, the greater the potential to reap the rewards offered. Previous research has suggested that the aims of a scheme may relate to data collection, sales promotion, more sophisticated strategic ends or any combination of these (Boussofiane 1996, Hart et al 1999). There is no evidence to suggest that all practitioners define loyalty in the same way. There is also substantial debate about the effectiveness and impact of such schemes as well as the motivations and operational mechanisms by which repeat purchase and or loyalty is engendered. Consumer privacy In recent years consumer privacy has become a greater concern due to expansion of direct and database marketing. These privacy issues might be expected to arise in loyalty schemes (Smith and Sparks 2003). Previous research has questioned the ethical basis of such data (Evans 1999) and provided evidence that consumers do have ‘underlying’ privacy concerns. More recent work has suggested that consumers are often quite ignorant of how loyalty card data is used (Graeff and Harmon 2002), and this may help explain their willingness to sign up for such schemes. If consumers have a loyalty card, then retailers know more about consumers that consumers know about retailers, and moreover can act on these data. Conspicuous consumption and the new consumer Conspicuous indicates the phenomenon of wasteful and lavish consumption expenses to enhance social prestige. Based entirely on observation more than a hundred years ago Thorstein Veblen (1899) proposed that American rich were spending a significant portion of their time and money on unnecessary and unproductive leisure expenditures and coined the term conspicuous consumption to describe the behavior. It plays an important role in the growth of a consumer society. Consumers are qualitatively different from those of the past: the simpler, rational consumer of the past was replaced by a more complex consumer. The importance of self and social images have given rise to the phenomenon where products serve as symbols, are evaluated, purchased, and consumed based on their symbolic content (Zaltman and Wallendorf 1979). Consumption has now become a means of self-realization and identification as consumers no longer merely consume products; they consumer the symbolic meaning of those products the image (Cova 1996). By adopting abstract interpretations and ascribing complex cultural meaning to products, those with higher taste but less money would aim to compete with those with money but no matching taste. Economic capital does not easily and necessarily translate into cultural capital. These taste symbols remain distinct from status symbols. Specific instances of this typical taste based consumption can be seen in such practices where marginalized art-forms, artifacts or working class outfits like jeans (Triggs 2001) are adopted as signs of exclusivity. Consumers become more educated and they no longer consider outrageous flamboyance and extravagant spending as the leading symbols of status. Tasteful expenditures than through flagrant exhibitions of wealth. The previous emphasis on acquisition and exhibition of physical items shifts to experiences and symbolic image in the post-modern phase (Pine, Gilmore and Pine 1999). An evaluation of the evolving literature However in the hand of these classical economic thinkers, the ideas of status consumption, bandwagon or snob were a set discrete of conceptual tools for explaining a so called irrational dimension of consumer behavior. The equilibrium relationship between price and status indicates signaling (Bagwell and Bernheim 1996) – Hirsch’s 1976 positional goods Ngs’ 1987 diamond goods and so on. Lack of comprehensive marketing and behavioral explaination of this important construct in socio-psychological models. This essentially suggests, once more, that if consumer behavior is often too complex to be handled by economics alone (Solomon 1992) and if done, may severely limit the scope of findings. Antecedents of conspicuousness Ostentation and signaling: The utility of some products may be to display wealth and power as was noted by Veblen and in spite of the evolution of postmodernism this motivation may remain strong among certain segments of customers. This segment as a result often finds pricing as a medium signaling wealth and status. These consumers attach great importance to price as a surrogate indicator of power and status because their primary objective is to impress others. Uniqueness This was first described by Leibenstein 1950 as snon effect. It may be considred as a function of personal, interpersonal and social effects factors; it takes into consideration personal and emotional desires when purchasing or consuming prestige brands, but it also influences and is influenced by other individuals’ behaviors (Mason 1995) – Understanding therefore is sometimes complex – Limited supply of a product actually increases consumers’ evaluation of a product. Moreover postmodernist ideas claim that consumers would reject the dominant values and everything that is normal. Doing their own thing. Need for uniqueness even further, encouraging consumers to interpret products differenyly, add meaning to them and invent newer ways of selc-expression and communication Social conformity In a postmodern society that would resemble a network of societal microgroups sharing strong emotianl links and a common subculture, consumers tend to adopt a more conforming mentality (Cova 1996) – Desire for public compliance – Both academicians and practitioners of marketing view conspicuous consumption as somewhat synonymous to the purchase of expensive luxuries or status products. Amaldoss and Jain (2005) – Marketers of conspicuous goods believe that demand might drop if they price their products lower – It is not obvious how consumer desire for uniqueness affects firm profits. Braun and Wicklund (1987) – Using the theory of self completion they concluded that the acquisition behaviour for material prestige goods is a function of identity crisis and insecurity, which are different from the classical understanding of the factors responsible for the same. Conspicuous consumption is massified as people are increasingly judged through their lifestyles (Varman and Vikas 2005) Conclusion: Class markers to some extent, are still guided by the classical Veblenian dynamics and material possession but the changing dynamics of socio economic structure is also being felt. Consumption patterns are largerly guided by the non functional symbolic properties of the products (brands). Moreover rapid expansion of information technology is enabling penetration of new cultural and social paradigms. This fundamental deviation in global consumer behavior may require, on the part of future research, an effort in establishing a new working definition of conspicuous consumption, involving additional psycho-social dimensions. This is especially needed in the context of transitional-traditional Asian nations, where direct evidence of cotemporary consumer behaviour is not always reported, as it may give an absolutely fresh impetus to marketing research in this area and open up whole new perspectives of the concept. Week 4 —“The purpose of marketing is to establish, maintain, enhance and commercialise customer relationships (often, but not necessarily always, long term relationships) so that the objectives of the parties involved are met. This is done by the mutual exchange and fulfilment of promises” —Grönroos (1990) Relationship approach to marketing in service contexts: The marketing and organisational behaviour interface, Journal of Business Research, 20(1): 3-11 —Paper builds on Berry (1983) ‘Relationship marketing’ in Berry, et al (eds) Emerging Perspectives on Services Marketing —Emphasis on interaction between suppliers and customers —Focus on maximizing the lifetime value of desirable customers and segments —Concerned with development and enhancement of relationships with key markets —Concerned with ‘internal’ market as well as external relationships —Quality, customer services and marketing intertwined - Payne et al 2000 Research begins The loyalty ladder Moving customers from suspects into advocates according to Payne 2000 – loyalty ladder —Zeithaml Rust and Lemon’s (2001) , customer profitability pyramid is an important approach to rank & prioritize customers, on the bases of the impact of the group of customers on the firm’s profitability (see Fig 6.2) Monitoring the client satisfaction becomes important Reading Continuance commitment is rooted in switching costs, sacrifice, lack of choice and dependence (Bandapudi and Berry 1997) – Might occur due to scarcity of alternatives or extra relational benefits. – The dark side of relational marketing according to Fournier et al., 1998 In a relationship consumers can experience both continuance and affective commitment to varying levels at any one point in time (Gilliland and Bello 2002; Fullerton, 2003). In employment relationships affective commitment has been shown to be strongly and positively related to employee retention in organizations (Allen and Meyer 1990) Affective customer commitment is negatively related to switching intentions. Affective customer commitment is positively related to advocacy. Continuance customer commitment is negatively related to advocacy intentions. Continuance customer commitment is negatively related to advocacy intentions. Continuance customer commitment is negatively related to switching intentions. There is an interaction between affective and continuance and customer commitment such that the negative relationship between affective customer commitment and switching intentions becomes less negative at higher levels of continuance customer commitment. There is an interaction between affective and continuance customer commitment such that the positive relationship between affective customer commitment and advocacy intentions becomes less positive at higher levels of continuance customer commitment. The research took place in banking services, telecommunications, and grocery retail services. Service quality and commitment drive the relationship. Implication of continuous relationships 1) low retention 2)negative advocacy 3) affects negative affective relationships. Just by being locked in is not a good thing for the relationship. The example of Tesco on 3,500 goods Transaction costs (especially information costs) lead to continuous relationships especially in a time-poor economy. Week 8