6 International context of e-waste management

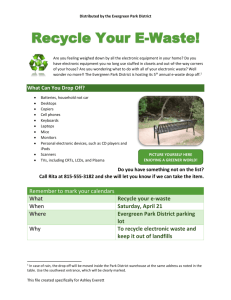

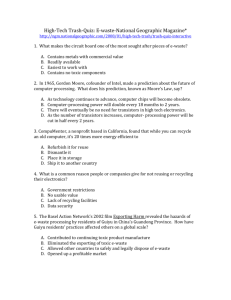

advertisement