Marinova, Dora. China and a global green system of innovation

advertisement

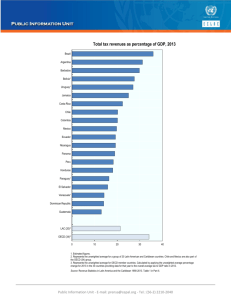

China and a global green system of innovation Dora Marinova, Curtin University Sustainability Policy (CUSP) Institute, Australia Xiumei Guo, Curtin University Sustainability Policy (CUSP) Institute, Australia Yanrui Wu, University of Western Australia Abstract The evidence provided by the science of climate change has triggered heated political discussion and a variety of economic measures aimed at reducing humanity’s ecological footprint. New sustainable technologies, including renewable energy, are paving the way for community values to encourage greater sustainable behaviour but technology impact assessment needs to be internalised in the innovation cycle in order to prevent humanity getting locked in other challenges similar to climate change. There are encouraging calls for sustainability to become the main focus of economic development. We describe this shift as a transition towards a global green system of innovation (GGSI). China’s contribution to the current environmental state of the planet is enormous, but so is its potential for decarbonising the country’s economy. The paper analyses recent trends and concludes that for China to play an active role in the changing global attitudes and the shift towards a global green system of innovation, it must become a leader in major institutional transformation including the development of education, public participation and governance. It also outlines why it’s unlikely that China will fulfil this role based on adopting a western type consumerist society, as well as provides a suggested approach for China, to focus on building balanced strategies that are representative of long-lasting Chinese cultural values. Introduction After three decades of high growth in GDP (9.7% per annum during 1978-20111), China has made substantial progress in economic development. In the world’s most populous country, associated with economic prosperity in recent years is the dynamic development in the area of science and technology. For example, China’s research and development (R&D) spending as a proportion of GDP (i.e. R&D intensity) amounted to 1.76% in 2010 and is anticipated to reach 2.50% in 2020 (Wu 2010)2. By then, China’s R&D intensity will be above the current mean for the OECD economies which stands at 2.33% (ABS 2010). The sheer volume of R&D investment at present, estimated at US$ 198.9 billion (Batelle 2012)3, is second only to USA with China recently overtaking Japan. The result of the expansion in R&D spending is rapid technological progress which is taking place in the country. Examples include the development of bullet (high-speed) trains, the surge of hi-tech export products and advancement in clean energy technologies. In fact, China has become the world’s largest investor in renewable energy and in 2010, 50% of all solar panels and wind turbines worldwide were manufactured there (Pew 2011). These phenomenal changes are regarded by some as a science and technology revolution (Zhang and Zheng 2009). China is also making a significant effort to improve its environmental image as since 2008 the country has been singled out as the highest greenhouse gas emitter in the world 4 and the current environmental performance index by Yale University ranks it 116th out of 132 countries5. More recently the government announced its commitment to the reduction of CO2 per GDP and a plan for transitioning towards a low-carbon economy (Guo et al. 2011). This 1 This growth rate was estimated using data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (www.stats.gov.cn). By comparison, Australia’s gross expenditure on R&D for all sectors (comprising business, government, higher education and private non-profit) amounted to 2.21% of GDP in 2008/09 (ABS 2010). 3 Australia’s gross expenditure on R&D are estimated to be US$ 21.8 billion in 2012 (Batelle 2012). 4 The Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency 2008 estimates show China’s GHG emissions 8% higher than US (www.mnp.nl/en/dossiers/Climatechange/moreinfo/Chinanowno1inCO2emissionsUSAinsecond position.html). 5 Environmental Performance Index 2012 (http://epi.yale.edu/epi2012/rankings); Australia ranks 48th. 2 'IAIA12 Conference Proceedings' Energy Future The Role of Impact Assessment 32nd Annual Meeting of the International Association for Impact Assessment 27 May- 1 June 2012, Centro de Congresso da Alfândega, Porto - Portugal (www.iaia.org) 2 is expected to be achieved through further investments in R&D and the development of new technologies. However, there is still not much realisation as to what China’s role is in relation to the greening the world’s economy. This paper puts into perspective some recent developments in innovation and argues that there is enough evidence to claim that the world is re-orienting towards a global green system of innovation in which China is already one of the most significant, if not the most significant, players. Systems of innovation Since the 1970s, innovation theory has been a very strong area of policy research and advice at government and industry level. It has predominantly focussed at the level of the firm, business enterprise and the market sector, despite evidence that innovation can also occur in public organisations, such as health, education or police (DIISR 2011). According to the latest edition of the Oslo Manual (OECD 2005), there are four types of innovation: product, process, organisational and marketing; all of which could be completely new or significantly improved compared to their predecessors. Irrespective as to where it is developed, the novelty criterion for innovation can be applied at the level of the firm (minimum requirement), a particular market, new to the world, or radical (disruptive) to prior knowledge and practices. Under the current imperatives of climate change, all types of innovation are very important when the main aim is to achieve a radical change in human behaviour (see Figure 1). New technology (product and process innovations), which is at the core of innovation, plays a crucial role in breaking up the dependence on fossil fuels and employing more environmentally sustainable ways of production, including food production, and living. However these new technologies will become innovation only after they have been commercialised and accepted by the market (OECD 2002). There is a Figure 1. The Innovation Concept wealth of knowledge about the importance and impacts of innovation for the performance of individual companies and countries but there is very little understanding as to the fact that innovation is only a means to achieving broader societal aims and goals. Hence impact assessment should be an internalised aspect of innovation rather than an add-on, external or after-the-invention activity. The innovation concept requires researchers, developers and all stakeholders to be assessing the impacts from the potential use of new technologies at the stage of its development. Preventing nuclear proliferation is an example of a ban on innovation based on its potential impacts; however there are many examples of new technologies being developed (e.g. nanotechnology) when there is hardly any understanding about their potential impacts. Technology development tends to follow certain trajectories or waves. The Natural Edge Project (Hargroves and Smith 2004) describes the current 6th technological wave as determined by sustainable technologies, such as renewable energy, biomimicry, green chemistry and green nanotechnology. According to Nisbet (2011), there is a strong need to merge the innovation network (motivated by energy insecurity) and the green network (motivated by climate change) which coined the new term grinn. The greening of technology is the essential characteristic of the new wave and this requires not only attention to societal goals but also to potential impacts in order to prevent another global crisis as we are currently experiencing in relation to climate change. At a policy level, innovation has been encouraged as the main way to achieve a competitive advantage. According to Scott-Kemmis (2004), there are significant differences Social impacts of mining at a local community level and the role of CSR for long-term sustainability 3 between countries in the way they invest in R&D, education, offer support to industry, take risk or encourage cooperation. The interplay of institutions and the interactive processes that generate and diffuse knowledge (OECD 2005) create national patterns of specialisation, or national systems of innovation, which tend to persist over prolonged periods of time making some countries better than others in the development and use of particular technologies. With the globalisation of the world economy, innovation has also changed. It has become: faster, multidisciplinary, collaborative (to reduce time, cut costs and share risks), democratised (no longer the domain of researchers, users/customers are also involved) and globalised (can originate from anywhere). These days the largest and the most technologically advanced US economy faces challenges from both ends of the spectrum – low and high – as far as its competitiveness is concerned (Council on Competitiveness 2006). Most importantly, the biggest challenge that the worldwide economy faces is to reform itself into a green economy where national innovation systems are geared towards supporting a global green system of innovation. Global green system of innovation The need for a fundamental change in the current technological wave is unprecedented as never before has humanity been subjected to impetus that it cannot control (see Figure 2). Individual national systems of innovation (as that of South Korea) alone will not guarantee the uptake of green technologies and super-national policies and innovation systems are needed that allow for development across the globe, including developing countries. A determining factor to achieve this is for the global community to adopt a vision for a sustainable world which will translate into changes in values and everyday practices as well as in a surge of human inventiveness activities. The signs of this are already appearing with the OECD countries signing the Declaration on Green Growth in 2009 and the UNEP’s Report on the Global Green New Deal (UNEP 2009) following the global financial crises. In 2011, the OECD officially released its Green Growth Strategy, which is about “fostering economic growth and development while ensuring that natural assets continue to provide the resources and environmental services on which our well-being relies. It is also about fostering investment and innovation which will underpin sustained growth and give rise to new economic opportunities” (OECD 2011: 4). The Strategy also includes specific recommendations, tools and indicators for measuring the progress. Business attitudes are also changing. According to a survey of 1,000 senior business executives from 12 countries (GE Global Innovation Barometer 2011), innovation will help “green” the world: 90% believe innovation to be the main lever for greener national economies Figure 2. Characteristics of the 6th technological wave and 85% are confident that innovation will improve environmental quality. There is also strong research evidence that green innovation contributes to competitive advantage (Chen et al. 2006). Green innovation is also becoming a significant area of research (Schiederig et al. 2011) with 88% of the publications clustering in the areas of business, humanities and social sciences. Social impacts of mining at a local community level and the role of CSR for long-term sustainability 4 The momentum building and the actual blocks of the emerging global green system of innovation are presented in Figure 3 and 4. Global Green System of Innova on Build momentum Coordinated ac vi es Green innova on clustering Adap ve governance and global ins tu onal alignment Visioning and longterm perspec ves Innova ve business and access to capital Global skills and talent Informa on flows and innova on exchange Green values and green innova on clustering Infra structure and suppor ng networks Educa on, R&D Global sustainability integra on Figure 3. Momentum building for a Global Green System of Innovation Figure 4. Building blocks of a Global Green System of Innovation China’s innovation system China has been widely criticised for the negative impacts its fast economic development has had on the country’s environment and its people. In the last ten years however the country has developed a very ambitious national innovation system targeted to become a world leader in green technologies. A major component of this was a 20.8% annual growth rate of increase of gross R&D expenditure, which has made the country the second largest investor in absolute terms (DIISR 20110). Cooperation with other countries is also strongly encouraged. For example, China is Australia’s 3rd most important research partner and 6th highest partner in publications (DIISR 2011). Its international patents have also skyrocketed (see Figure 5). In 2004 China became the world’s leading exporter of ICT, including mobile phones, digital cameras and laptops (OECD 2005). There has also been a concerted effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Between 1990 and 2005 China reduced its carbon intensity by 44 %, a further 40-45% reduction by 2020 was pledged in Copenhagen, including the 17% reduction by 2015 in its current 12th Five-year Plan. China is now the world’s largest China’s innova on Figure 5. US patents by China by date of application, 1976-2008 (absolute number and per 100,000 US patents Clean Development Mechanism Figure 6. Approved CDM projects in China, 2005–2011 Social impacts of mining at a local community level and the role of CSR for long-term sustainability 5 investor in clean energy and in 2009 surpassed US in total installed clean energy capacity (Pew 2011). Interestingly, China’s national budget is very much oriented towards addressing the priority of climate change with $1 spent on climate change against $2-3 spent on traditional military tools in 2011, compared with $1 to $41, respectively, for US (Pemberton 2010). The country’s political stability has also attracted the lion’s share and growing numbers of CDM (clean development mechanism) projects (see Figure 6 and 7). Clean Development Mechanism The governance model used in China’s national innovation system is described as populist authoritarianism (Dickson 2005), meritocracy, consultative Leninism, economic pragmatism or good governance with Chinese characteristics (Tzang 2011) but it aims to unite its people in building the country’s resilience and capacity to deal with climate change. Conclusion The innovation system concept is ultimately about people – “the knowledge, technology, infrastructure Figure 7. International distribution of CDM, 2011 and cultures they have created or projects projects adopted, who they work with, and what new ideas they are experimenting with” (DIISR 2011: iii). People’s voices are most loudly heard when they are directly affected by pollution, droughts, floods or other climate related calamities, but they also have an active role to play in gearing the world towards a green economy. A global green system of innovation will not put a stop to competitiveness and/or collaboration. It is however a realignment of priorities and making a change on a new path of innovation activities. It also requires impact assessment to become an inherent aspect of innovation which assists in achieving the broader societal aims. We are already seeing the global role of China emerging through its efforts to decarbonise its economy and invest in green technologies (domestically, internationally and for capacity building in other developing countries). Most importantly, for the global green innovation system to become a reality, there is a role to play for every nation and every researcher as we are all sharing the same concerns and love for the planet Earth. Acknowledgement The authors acknowledge the support of the Australian Research Council. References Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2010), Research and Experimental Development Australia 2008–09, Cat No. 8112.0, Canberra. Batelle (2012), 2012 Global R&D Funding Forecast, http://www.battelle.org/ABOUTUS/rd/2012.pdf (16.02.2012). Chen, Y., Lai, S. and Wen, C. (2006), “The Influence of Green Innovation Performance on Corporate Advantage in Taiwan”, Journal of Business Ethics, 67: 331–339. Council on Competitiveness (2006), Regional Innovation – National Prosperity, http://www.compete.org/images/uploads/File/PDF%20Files/Regional%20Innovation%20 National%20Prosperity.pdf (8.04.2012). Social impacts of mining at a local community level and the role of CSR for long-term sustainability 6 Department of Innovation, Industry, Science and Research (DIISR) (2011), Australian Innovation System Report 2011, Australian Government, Canberra. Dickson, B. J. (2005), “Populist Authoritarianism: The Future of the Chinese Communist Party”, Conference on “Chinese Leadership, Politics, and Policy”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peacehttp://www.carnegieendowment.org/files/Dickson.pdf (8.04.2012). GE Global Innovation Barometer (2011), An Overview on Messaging, Data and Amplification, http://files.gereports.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/GIB-results.pdf (8.04.2012). Guo, X., D. Marinova and J. Hong (2011), “China’s Shifting Policies towards Sustainability: A Low-carbon Economy and Environmental Protection”, Journal of Contemporary China (forthcoming, acceptance date 19.07.2011). Hardroves, K. and Smith, M. (eds) (2004), The Natural Advantage of Nations: Business Opportunities, Innovation and Governance in the 21st Century, Earthscan, London. Nisbet, M. (2011), Climate Shift: Clear Vision for the Next Decade of Public Debate, American University School of Communication, http://climateshiftproject.org/report/climate-shift-clear-vision-for-the-next-decade-ofpublic-debate/ (8.04.2012). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2002), Frascati Manual: Proposed Standard Practice for Surveys on Research and Experimental Development, Paris. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2005), Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, Third edition, OECD and Eurostat. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2011), Towards Green Growth: A Summary for Policy Makers, May 2011, www.oecd.org/dataoecd/32/49/48012345.pdf (8.04.2012). Pemberton, M. (2010) Military vs. Climate Security: The 2011 Budgets Compared, Institute for Policy Studies, US. Pew Charitable Trusts (Pew) (2011), Who’s Winning The Clean Energy Race? 2010 Edition: G-20 Investment Powering Forward, http://www.pewenvironment.org/uploadedFiles/PEG/Publications/Report/G-20ReportLOWRes-FINAL.pdf (16.02.2012). Schiederig, T., Tietze, F. and Herstatt, C. (2011), “What is Green Innovation? – A quantitative literature review”, XXII ISPIM Conference. Scott-Kemmis, D. (2004), Innovation Systems in Australia. ISRN 6th Annual Conference Working Paper, www.utoronto.ca/isrn/publications/WorkingPapers/Working04/ScottKemmis04_Australia.pdf (17.10. 2008). Tzang, S. (2011), “Consultative Leninism: China's new political framework”, Journal of Contemporary China, 18(62): 865-880. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2009), Global Green New Deal: Policy Brief, http://www.unep.org/pdf/A_Global_Green_New_Deal_Policy_Brief.pdf (8.04.2012). Wu, Y. (2010), “Indigenous Innovation for Sustainable Growth”, in Garnaut, R., J. Golley and L. Song (eds) China: The Next 20 Years of Reform and Development, ANU E Press, Brookings Institution Press & Social Sciences Academy Press, Chapter 16, 341-61. Zhang, X. and Y. Zheng (2009), China's Information and Communications Technology Revolution: Social Changes and State Responses, Routledge, Oxford. Social impacts of mining at a local community level and the role of CSR for long-term sustainability