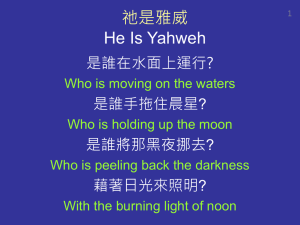

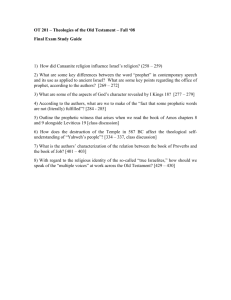

the sovereignty of yahweh in the book of proverbs

advertisement