ARTICLE

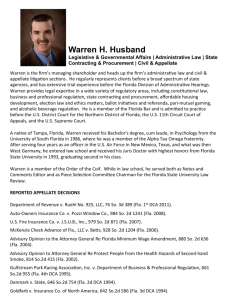

advertisement