Transcript of this slide

advertisement

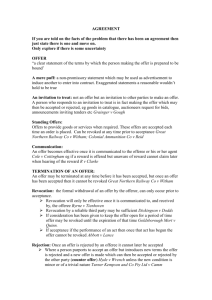

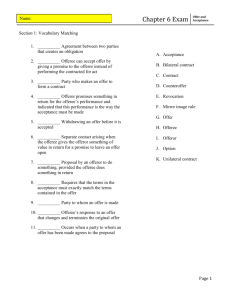

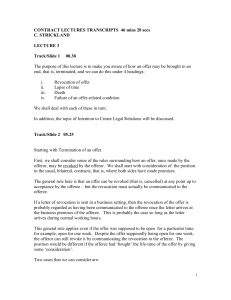

CONTRACT LECTURES TRANSCRIPTS 46 mins 20 secs C. STRICKLAND LECTURE 3 Track/Slide 2 05.25 Starting with Termination of an offer. First, we shall consider some of the rules surrounding how an offer, once made by the offeror, may be revoked by the offeror. We shall start with consideration of the position in the usual, bilateral, contracts, that is, where both sides have made promises. The general rule here is that an offer can be revoked (that is, cancelled) at any point up to acceptance by the offeree – but the revocation must actually be communicated to the offeree. If a letter of revocation is sent in a business setting, then the revocation of the offer is probably regarded as having been communicated to the offeree once the letter arrives at the business premises of the offeree. This is probably the case so long as the letter arrives during normal working hours. This general rule applies even if the offer was supposed to be open for a particular time, for example, open for one week. Despite the offer supposedly being open for one week, the offeror can still revoke it by communicating the revocation to the offeree. The position would be different if the offeree had ‘bought’ the life-time of the offer by giving some ‘consideration’. Two cases that we can consider are: Byrne v Van Tienhoven 1880 and Dickinson v Dodds 1876 In the Byrne v Van Tienhoven case, the dates are crucial. The defendants made an offer to sell some tin plate in a letter posted on 1st October. The defendants then posted a letter revoking the offer on 8th October and this letter reached the plaintiffs on 20th October. Meantime, on 15th October the plaintiff had posted a letter accepting the offer. It was held that the contract stood. The plaintiffs did not know of the revocation of the offer until after they had accepted the offer. In other words, the revocation of the offer was not communicated to the offeree in time. 1 The Dickinson v Dodds case is authority for the proposition that actual knowledge of revocation of an offer may come from not only the offeror himself but from a THIRD PARTY. In this case on 10th June 1974 Dodds offered to sell his house to the plaintiff for £800 promising to hold the offer open for 2 days – until 9am on the 12th June. Nevertheless, on the next day, 11th June, he sold the house to someone else. Dickinson became aware of this fact from his own agent, Berry, but still purported to accept the offer to buy the house by 9am on the 12th. Dodds refused this acceptance as he had already sold the house. Dickenson thus brought an action for specific performance of the contract. The Court of Appeal held that he was not entitled to specific performance. He had been notified that the house had been sold to someone else by his own agent and this amounted to notification of revocation of the offer, so he could not accept it. What we are not sure about from this case is the degree of reliability that is needed in the person who notifies the offeree of the revocation. It is suggested that if an offer is revoked by someone other than the offeror himself then the onus is on the offeror to show that the offeree learned of the revocation through a ‘trustworthy’ source – see Cartwright v Hoogstoel 1911. Keeping an offer open for a number of days or weeks is therefore not binding in itself as it can be revoked. As noted above, it would only be binding if supported by some form of consideration – for instance, if the offeree paid an amount of money to the offeror to keep the offer open. 2