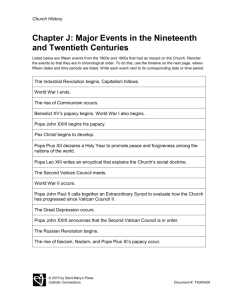

THE BROKEN CROSS

advertisement