Agbiji_Development&violence

advertisement

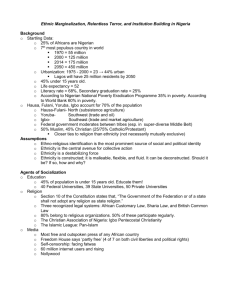

Engaging Christian faith communities in development in the context of violence Dr. Obaji Agbiji, Research Institute for Theology and Religion, University of South Africa Email: obajiagbiji@gmail.com. Cell phone Nr: +27739206598 Introduction A number of African Christian faith communities are experiencing a high proportion of violence in their respective countries. Some of the Christian communities that are worse hit include those that are in countries like Nigeria, Kenya, Cameroon and Sudan. Whilst various factors including poverty and ethnicity account for violent conflicts, religious violence and in particular militant Islam under the auspices of organisations such as Boko Haram, Al-Shabab and others poses the greatest threat to both the existence of Christian faith communities and their ability to respond to the socio-political and economic challenges of their societies. It has therefore become pertinent for churches to evolve innovative ways to continue to bear witness through their teachings and actions in such violent contexts. The teachings and actions of the institutional church that could be termed innovative but also sustainable will need to be sought for from the resources that are inherent in ecclesial communities and such that speak to the very nature of the church. To aid our understanding of the major cause and persistence of religious violence in a number of countries in Africa including Nigeria, this paper will be informed by Ninian Smart’s (1996) phenomenological paradigm of religion. Smart opines that power animates the various dimensions of religion. As such the will to appropriate the absolute power of God drives religious leaders and especially preachers who see themselves and are seen by their followers as having received enlightenment or revelation from the Supreme Being and are following in the footsteps of prophets of monotheistic religions (Islam, Christianity and Judaism) (Smart 1996; cf. Popular Discourses of Salafi Radicalism and Salafi Counter-radicalism in Nigeria, hereafter Popular Discourses 2012:119). Accordingly, the enlightened or contemplative personality could assume the status of a guru, mystic, hermit, monk, nun, pastor, prophet, preacher or Imam. His or her religious pursuits are often geared towards merging the self into some union with the sacred or powerful other through worship of and dependence on the powerful other. In this sense, this personality who 1 may be a prophet or preacher who has experienced this numinous religious experience sees himself or herself as a representative of the powerful other, speaking and acting on behalf of the powerful other. Such a personality could achieve arrogance and indeed pride. This preacher, prophet or religiously enlightened personality and follower can even “catch the fear-making mode and take on what is supposedly divine anger” (Smart 1996:172), thereby making the preacher or follower awe-inspiring in his own right. This accounts for “why the preacher or follower (religious enlightened person), who in his ritual function stands as the mouthpiece of the (Lord) powerful other, can easily begin ranting” or even taking violent actions (Smart 1996:172). Smart’s phenomenological paradigm of religion could therefore account for the audacity, arrogance and religious motivations that the leaders and members of Boko Haram tend to exude and the power they seek to acquire within the Nigerian sociopolitical context. In addition, the phenomenological paradigm could assist in the understanding of the reasons that have given rise to Boko Haram and its ideology given some arguments touching on economic factors that have given rise to the emergence of the group as presented by some scholars and social commentators such as Olojo (2013:1,2) and Carson (2012). Violence is defined in this paper as injurious or lethal harm meted out through physical actions in the context of war or terrorism. (Cavanaugh 2009:8). Based on this understanding, religious violence is a religiously motivated injurious or lethal harm meted out by a person or group of persons to other persons or groups of persons who are perceived to be of a different religious view. Development in turn is understood as referring to spiritual and material progress that results in the general wellbeing of humans, the environment and socio-political and economic systems in a given society (Agbiji 2012:21). Proceeding then from this introductory background, I intend to draw upon open sources to present my arguments while also acknowledging the absence of literature on the Nigerian Christian faith community and her response to poverty and violence through the diaconal ministry. I will first pay attention to the socio-political and religious challenges of Nigeria and the activities of Boko Haram before proceeding to give an account of how the church is so far engaging in development in the face of intense violence. I will then propose the engagement of the concept of Christian diaconia as a pertinent approach that could deepen the response of Christian faith communities to the challenges of underdevelopment and militant Islam in Nigeria. Whilst the Nigerian case does not effectively represent what is 2 obtainable in all African faith communities and their response to violence, it could at least generate some reflections on possible actions that can be initiated in other African contexts. The Nigerian socio-political and religious context Nigeria like other African countries is multi-ethnic, multi-religious and underdeveloped, with a large population of her youth unemployed. Within the structural violence approach, such a context provides a fertile ground for dangerous persons or groups to find support for terrorism (Olojo 2013:1,2; Harnischfeger 2014:35; Carson 2012). Scholars argue that in Nigeria, religion is politicised and politics is “religionised” (Agbiboa 2013:8; Mohammed 2014:23). Agbiboa (2013:3) has further argued that Islam is emblematic of the religionpolitics nexus and this marriage of religion and politics could be historically traced to the days of Prophet Muhammad, the founder of Islam. Based on this perception, Boko Haram, its members and supporters see themselves as rising in defence of Islam especially in the restoration of the Caliphate founded by Usman dan Fodio and joining forces with the Muslim Umar in fighting Jihad against the western world and its Christian allies in Nigeria (Harnischfeger 2014:43, 47,51 cf. HRW 2012:26,30). The religious intent of Boko Haram which seeks to re-enact Islamic theocracy in Nigeria after the manner of the Prophet of Islam through Sharia can hardly be dissociated from its ideology and operations. The religious agenda of Boko Haram can therefore be traced from the inception of the group to its present ideology and operations. Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati Wal-Jihad1 popularly known as Boko Haram came to public notice in Nigeria in 2009 but the origin of the group can be traced to 1995 (Mohammed 2014:9) and the group can be seen in the broader context of Islamic movements that espouses unorthodox beliefs and unconventional religious practices. These groups are often linked to ethnic and religious violence in Nigeria, most notably the Maitatsine group active in the 1980s (Popular Discourses 2012:120). It is believed that the initial membership of the group comprised Muslim students from the University of Maiduguri who dropped out of school in response to the preaching of a foreign Islamic scholar who convinced them that Western education was haram (unlawful) in Islam (Olojo 2013:2,3). When translated from Hausa to English Boko Haram means “Western education is sinful”. Boko Haram identifies itself as Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati Wal-Jihad, which means “People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad” in Arabic. 1 3 The initial leadership of Boko Haram under the regime of Mohammed Yusuf is believed to have garnered a large following of poor families and unemployed youths from northern Nigeria, as well as neighbouring countries such as Niger, Chad and Cameroon. These followers were enrolled in Yusuf’s religious complex, which included a mosque and school used for ideological orientation and propagation. Boko Haram also initiated social programmes aimed at assisting the poor and indigent (Olojo 2013:3). These initiatives appeared to be laudable especially when viewed from the perspective of some analysts from the West and elsewhere who argue that the rebellion of Boko Haram is born out of poverty, illiteracy and unemployment; and a response to corruption and social neglect (Harnischfeger 2014:35). However, Harnischfeger argues that interpreting the rise and activities of Boko Haram as a protest against deteriorating living conditions is at odds with the statements of the leaders of Boko Haram, who insist on the religious motives of their insurrection: “This is a war between Muslims and non-Muslims…This is not a tribal war, nor is it … a war for financial gains, it is solely a religious war”2 (Harnischfeger 2014:35). Whereas it initially appeared as if Yusuf’s assemblage of his followers was in sympathy with the poor and indigent in society, his teachings reveal a sinister plan. The message of Boko Haram was articulated by its leader Mohammed Yusuf. Yusuf’s teachings were derived from and reflect the extant discourse and ideology of radical Islamism worldwide, with which Yusuf had become used to. The main narratives of Boko Haram, as outlined in Yusuf’s sermons, were distributed widely throughout northern Nigeria through audio tapes and open-air sermons. The major content of his sermons were the rejection of secularism, democracy, Western education and Westernisation (Mohammed 2014:15). The rejection of secularism and the pursuit of its replacement by Shariah is a current in radical Islam that goes back to the fourteenth century Damascene scholar Ahmad Ibn Taymiyyah (1268-1328 CE). Yusuf also followed in the steps of Saudi Arabia Islamic scholars such as Sheikh Bakr Ibn Abdallah Abu Zaid (1944-2008) who consistently attacked democracy and the freedoms it stands for as anti-Islamic. The teachings of Yusuf otherwise referred to as the Yusufiyya dawah3 was built around a close-knit group of followers, who believed in the justness of their cause and offered unalloyed loyalty to their leader (Mohammed 2014:15). Abubakar Shekau the leader of Boko Haram in a video message, in (Anon.), “Jos Bombing: Text of video Statement by Jama’atu Ahlus-Sunnah Lidda’awati Wal Jihad”, Elombah, 28 December 2010. 2 3 The dawah is a major feature of radical Islam in the Muslim world. It is [an] Islamist term which denotes a combination of propaganda, education, medical and welfare action – and its practitioners. Yet the da’awa has an 4 Yusuf’s sermons are known to justify the reasons for his endeavours as a divine mandate which places him and the members of Boko Haram as following in the steps of Prophet Mohammed. The members are often encouraged to lay down their lives and resources to the mission of the group and often assured of victory and eternal reward from Allah. The sermons are audacious and persuasive to his listeners with an indication of a battle cry aimed at inciting and emotionally arming his followers and listeners to rise to the occasion (Mohammed 2014:15). In line with Smarts argument on the phenomenology of religion, Yusuf takes on himself the position of the powerful other (divinity) to fight for him/her as the Prophet did. Yusuf was taking advantage of the poor economic condition of his unsuspecting audience and their religious sentiments to radicalise them and to raise an army for the Islamisation of the nation, beginning from Borno state, the stronghold of their operation. This makes sense especially when we remember that the real influence of religious leaders depends on the numbers of followers (Popular Discourses 2012:122) and how well these leaders are able to indoctrinate their followers on the course of action expected from them. Yusuf’s message to the State, Federal government and its security establishments could further shed light on the level of arrogance that the leadership and membership of Boko Haram has assumed. After one of many of his defiant sermons, [Yusuf] thus concluded the sermon by issuing his so-called ‘open letter’, which he contemptuously addressed to ‘the fake President of Nigeria and Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces’ and copied to all the security chiefs: air force, army, navy, police and state security service, members of the national assembly, and the ‘lowly weakling’ Governor Ali Sheriff of Borno State, warning them that he and his followers would not let the shooting of his followers be in vain and clearly threatening retaliation (Popular discourses 2014:130). The open letter stated the following: With your command and knowledge, 20 of our fellow believers have received gunshots and wounded by soldiers. We do not approve. We will not approve. We are not going to tell anyone [i.e. we will keep our plan of attack secret], and that is why we have issued this open letter. By God, I do know that you would all receive my words because I invited everyone to come, and some will take what I have said to you. So let it be translated into English for you, for I do not speak English. Therefore we do not accept this terrorism. The shooting of 20 persons we do not accept, and we will not forget nor forgive it. Second, we do not agree with the crazy soldiers importance beyond that of being a possible cradle for violence. It is bringing about change in many Muslim societies, and sometimes plays a role – albeit indirect – in politics (Mohammed 2014). Yusufiyya dawah means the propaganda, education, medical and welfare action of Yusuf and his followers. 5 and mobile policemen of the Operation Flush patrolling the streets of Maiduguri; for peace to reign, they must be removed from among the civilians. You keep talking about peace, peace, and peace. Since you worship peace as your pagan god, you can worship it in that way. That is my letter (Popular discourses 2014:130). Johannes Harnischfeger (2014:34) has well observed that “what Boko Haram is fighting for – the Islamisation of state and society through a strict application of Shariah – was propagated by Hausa and Fulani politicians more than ten years ago”. The religious factor remains constant in all crisis that have arisen in Nigeria such as the pogrom of the 60s, Maitatsine riots of 1980s, Sharia riots of 2000 (Zamfara, Kaduna and other northern states), beauty pageant riots, Mohammed cartoon in Denmark riot, 2011 election riots, Jos riots, etc. Boko Haram like other Islamic militant groups perceives Christians as enemies and legitimate targets for violent attacks (Mohammed 2014:19), with the ultimate aim of intimidating Christians and subjecting them to Islam. So far, Boko Haram has carried out numerous attacks on churches and Christians in northern and central Nigeria during its campaign of violence. In July 2009, they launched violence for five days killing 37 Christian men, including three pastors, and set ablaze 29 churches in Borno State. Armed gunmen have bombed or opened fire on Christian worshippers in more than 18 churches across eight northern and central states, killing more than 127 Christians, injuring numerous others (HRW 2012:44). In Borno State alone, between June 7, 2011 and January 17, 2012, 142 Christians were killed. The attacks on Christians in northern Nigeria appear to be a part of a systematic plan of violence and intimidation. Boko Haram attacks on Christians includes abductions (including the 250 girls from Chibok), forced conversions, attacks in markets and during Christian services using guns, improvised devices, swords or suicide bombers (HRW 2012:44,45). Indeed, Cameron Thomas, international Christian Concern Regional Manager for Africa has noted that the latest (June, 2014) attack by Boko Haram on four churches and those innocently attending Sunday services inside once again affirms the religious motivation of this group's heinous crimes against the Nigerian people. For years, the Christian population of northern Nigeria has faced a devastating offensive by Islamic militants that has yet to be effectively countered. He further adds: "Today, the bloodied soil of Kwada and Kautikari villages serve as a heart-rending cry for greater action to ensure the safety of Christians wishing to exercise their right to practice their beliefs free from fear of retribution at the barrel of gun or trigger of an explosive" (Zaimov 2014). It is no longer in doubt that 6 Christians in Nigeria are facing enormous persecution and martyrdom from the hands of Muslims and Boko Haram. Above all Boko Haram has declared war against Christians and they are employing all of their resources derived from within and outside of Nigeria to achieve their jihadist agenda. The crucial question is how is the church in Nigeria responding to the crisis it is facing in the midst of harsh economic realities? The response of the Church to poverty and Islamic militancy The response of the Nigerian church to underdevelopment and Islamic militancy can be summarised into five categories namely: prayer, relief/social services, inter-religious dialogue, advocacy and retaliation. Prayer is often the first response of Christian leaders, churches and other Christian groups to the menace of poverty and Islamic militancy in Nigeria. The dimensions of these prayers include supplications and intercessions to God for the improvement of living conditions, protection of Nigerians against terrorism, comfort for affected persons, and exposure of members and supporters of the group and corrupt persons. The prayers are also directed at the terror group for a change of heart on the part of its members so that peace and harmony will be restored to the Nigerian society. One of the numerous instances of the call for prayers and indeed prayer sessions was that called for and led by a Christian leader, Joseph Otubu, in Lekki, Lagos. Otubu (2014), a leader of Cherubim and Seraphim Church Worldwide called on both Christians and Muslims in Nigeria, to turn onto God for enduring solutions to Boko Haram and other security problems through fervent, genuine prayers and supplications. Otubu believes that God could “touch the hearts of Boko Haram sect members to stop killing innocent people and destroying their property because it is God who created them”. He argued that the Christian’s “weapon of warfare is spiritual and not carnal". In addition to prayers the Christian community is involved in relief and social services as a means of addressing poverty and the challenge of violence. The most significant contribution of both the church and her leaders to Nigerian society, from the time of the missionaries to modern times, may be said to be in the area of relief and social services. The churches and church leaders have been consistent in this social approach through their denominations and ecumenical bodies. According to C. I. Itty, (in Swart 2006:18), relief/charity and social services encompass “a substantial range of categories: education, health services, social welfare and some sort of economic development”. These 7 charitable and social service activities were aimed at conversion, literacy, poverty alleviation and the improvement of the wellbeing of Nigerians, especially in moments of crisis (Agbiji 2012). For example, during and after the Nigerian civil war, repeated religious riots and the insurgency of Boko H aram, church leaders, churches and ecumenical church organisations in Nigeria, with the support of the World Council of Churches (WCC) and overseas partner churches, have been deeply involved in relief and reconstruction activities. These activities have always contributed immensely towards ameliorating the sufferings of both Christians and non-Christians throughout the country (Agbiji 2012:118-120; PCN Communiqué 2014:13). Another pertinent area of the church’s response to religious violence and its concomitant outcome such as destruction of property and underdevelopment is inter-religious dialogue. John Cardinald Onaiyekan (2010:7), immediate past president of CAN, Catholic Archbishop of Abuja and immediate past co-chairman of the Nigerian Inter-religious Council (NIREC), asserts that “inter-religious dialogue is perhaps the best way to describe what we understand by management of our religious diversities”. Onaiyekan (2010:7) argues further that [t]he concept of dialogue is based on the assumption that we can actually talk to one another and understand one another; that we can devise a common language to communicate with each other. It is based on the conviction that we have common grounds, despite the differences in the way we practise our religions and, sometimes, also the way the tenets of our faiths are formulated and proclaimed. The perennial challenge of Islamic fundamentalism in Nigeria, which has brought about colossal destruction of human lives and property worth billions of Naira across the country, has given impetus to the need for dialogue. It is to the credit of Nigerian church leaders, some Islamic leaders and Nigerian government under the auspices of CAN and NIREC respectively, that the initiative to engage in dialogue with Islamic leaders constitutes such a giant step towards the socio-political and economic development of Nigerian society (Agbiji 2012:121; CAN 2010: 15; Abubakar 2010:1; CAN 2004:2; America 2004:6). Beyond the confines of prayer, charity and social services and inter-religious dialogue, advocacy stands out as another platform through which Christian religious leaders have registered a significant contribution in Nigeria. The Nigerian Christian community engages in advocacy through the leadership of its ecumenical structures such as the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN), its subsidiaries 8 and Church denominations. Christian religious leaders operating under the auspices of CAN are of the view that ‘the most important political duty which CAN often performs is its warning and prophetic function’ (CAN 2010:13). It is this ‘warning and prophetic function’ that could play an important advocacy role in the transformation of Nigerian society. Church leaders in Nigeria are in the main engaged in advocacy through communiqués, press releases and messages from both the pulpit and the mass media. As part of this development, it is significant to observe how it has become characteristic of denominational and ecumenical church bodies to issue public statements at the conclusion of their major meetings – i.e. statements that relate to socio-religious, economic and political issues (Agbiji 2012:128; CAN 2012; CAN 2014a; CAN 2014b; CAN 2014c; CAN 1988:48-50; Mbachirin 2004:654; CAN 1988:9-12; Williams 1988:11). Yet, in contemporary Nigeria, a large number of Christians point to issues of political dominance and violence as the motives of Islam in Northern Nigeria, ultimately aimed at stretching the frontiers of Islamic aggression to other parts of the country. This perceived threat is interpreted differently within the Christian community in Nigeria. Conservative Christians take a cautionary look at pockets of Islamic dissent as unitary actions which must be addressed as such, through either dialogue or soft threats. Christians of the mainline (orthodox) denominations often toe this line of thought. The more radical Christian groups which can be associated with the Pentecostal tradition present the narrative of a jihadist game plan to overwhelm Nigeria with a religious and ethnic agenda. The latter group find dialogue rather deceitful, and this demography mainly comprises a largely youthful population that has grown up in a Nigeria that has acquired with time new identity constructions, which have revolved around ethnicity and religion (Mang 2014:90). It should however be clarified that given the huge influence of Pentecostalism on mainline denominations, it is increasingly becoming difficult to delineate responses of individual Christians to Islamic militancy based on their denominational traditions. What this means is that as against the official position of the Roman Catholic Church in Nigeria which may be disposed to dialogue for instance, a Roman Catholic member who has imbibed Pentecostal ideology may find dialogue as unhelpful and may resort to violent response to Islamic insurgency. The response may also be influenced by how the activities of Boko Haram are 9 perceived. The perception that could for example attract a violent response and retaliation may be such that views Islam as being at war with Christianity. The issue of organised crime and violence perpetrated by Islamic terrorists such as Boko Haram against Christians is further giving impetus to the consideration of violent responses on the part of Christian youths against Muslims. Archbishop Ben Kwashi describes the ongoing experiences of Christians when he states that “Muslim attacks on the church seem to be a permanent feature in northern Nigeria. After each attack many Christians are immediately left with the loss of the lives of their relations (sometimes those killed are the bread-winners of the family), and of property” (Kwashi 2004:65). In view of the perennial nature of these acts of organised crime and terror, Kwashi (2004:68) further argues that many suffering Christians have changed their attitude to violence. All along, Christians in Nigeria have maintained a strong belief in the scripture that says: “But I say to you, that you resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite you on your right cheek, turn to him the other also.” Today, some Christians no longer hold strongly to this view. Such Christians will question: ‘The Muslims have slapped us on one cheek; we have also turned the other cheek, now which other cheek do we have to turn?” By this they tend to imply that they need to fight back and resist the Muslims whenever they are attacked. The reinterpretation of the teachings of Jesus could be viewed as a serious departure from the usual pacifist and non-violent resistance stands which have often characterised the theological understanding of Christians of the two doctrinal persuasions as it concerns the passage in view (Luke 6:29). Admittedly, this may be perceived as an extremely radical departure from the teachings of Christ and it may even be considered to be inconsistent with biblical teaching and, therefore, heretical. However, it is not possible to dismiss the repeated pain and losses that these Christians have been enduring over the years. Undoubtedly, Christians in different contexts of suffering have often developed a theological framework which has guided and sustained them to “weather their storms”. Accordingly, these Christians in northern Nigerian have devised a theology which they assume will satisfy their needs and they will adhere to this theology unless church leaders provide a more relevant theology that meets their existentialist needs (Agbiji 2012:138,139). Also, within the context of prophetic theology - a theology that is time bound and addresses a specific social issue (oppression) in a particular context, at a particular time (Higginson 2009:34) such as the Nigerian Islamic militancy against Christians, such a theology can arguably be deemed appropriate. 10 Yet, R. Niebuhr has warned that the religious person can be tempted to claim divine sanction for very human and harmful actions. They can be tempted to equate their particular interests with eternal truth (Niebuhr 1937, Cited in Graybill 1995). Niebuhr’s warning is in tandem with Smart’s phenomenology of religion. It could be assumed to be calling to question the extra-judicial actions of Islamic terrorists who lay claim to a divine mandate and Christian extremists who also kill in self-defence based on a theological stance. Whereas Niebuhr’s warning is pertinent, the initiatives of the church through its ecumenical and denominational platforms in response to various forms of Islamic militancy including Boko Haram could be considered commendable. These commendable initiatives include prayer, relief/social services, inter-religious dialogue and advocacy. It is however doubtful if the Nigerian Christian faith community has exhausted its resources in its quest for a sustainable presence and witness in the Nigerian society, in view of the challenges posed by underdevelopment and Islamic militancy. My view is that in addition to the existing dimensions of engagement with the ongoing challenges as mentioned above, the various expressions of the church (ecumenical, denominational, congregational and personal) could still evolve other strategies that will not just assist the church to “survive the crisis”, but such measures that could enhance the church’s witness and could forestall the re-occurrence of similar crisis in the future. Above all, a strategy that is inherently entrenched in the very nature of the church could place the church on a vantage position to blossom through the transformation of crisis to opportunity for the manifestation of Christian neighbourly love, creation of inclusive communities, caring for creation and struggling for justice. These are crucial Christian tenets that show the Gospel in action through the diaconal ministry of the church. The concept of diaconia and its social implication in addressing poverty and Islamic militancy Although the concept of diaconia is hardly used in many African Christian communities including the Nigerian ecclesial community, the Church has always been involved in social services through relief and charitable deeds, medical services, provision of education, advocacy and economic empowerment schemes (Agbiji 2012). In addition, the Church has been engaged in inter-religious dialogue and collaborative endeavours with the government towards addressing social challenges. All of these activities rightly belong to the domain of Christian diaconial ministry. 11 It seems to me that the time has now come for churches to initiate a move towards the effective use of the concept of diaconia in the social ministry of the church in Nigeria and other African countries for the following reasons: Diaconia has a theological richness that can give strong guidance to the church’s social ministry. The content of the concept of diaconia speaks directly to the needs of the African context and at the same time reveals the essence of the church in response to the needs of the society. The concept of diaconia is strongly rooted in the history of the Christian church and could provide a common ground for the much needed collaborative engagement between the church in Nigeria, other African societies and other Christian communities in other parts of the world. The need for collaborative engagement is particularly pertinent in addressing poverty and Islamic militancy in Nigeria and elsewhere in Africa. Kjell Nordstokke (2014:65) has argued that the concept of diaconia (diakonia) developed in the course of church history, and it has been strongly impacted by the diaconal movement initiated in Germany in the 1830s with its focus on providing health and social services. In finding a theological grounding for the diaconal practice, biblical material was addressed, especially passages that contain the so-called diak-words (diakonein, diakonia and diakonoc), which often are translated as serve, service and servant, respectively. Diaconal movement scholars like Kittel (1935), have interpreted these words as “active Christian love of the neighbor” (Nordstokke 2014:65; cf. Kittel 1935). Christian diaconia is therefore rooted in the Gospel teaching according to which the love of God and the neighbour are a direct consequence of faith. As such the diaconal mission of the church and the duty of each of its members to serve are intimately bound up with the very notion of the church and stem from the example of the sacrifice of our Lord Himself, our High Priest, who, in accordance with the Father’s will “did not come to be served but to serve and to give up his life as a ransom for many” (Matthew. 20:28) (Ecumenical documents nd:175,176). In deriving its essence from the example of Christ and as an indispensable attribute of the community of faith, the ultimate goal of Christian diaconia is the salvation of humankind from everything which oppresses, enslaves, intimidates, destroys and distorts the image of God, and in doing so, to open the way to salvation. This understanding of diaconia inevitably calls the Christian community to a life of individual and cooperate sacrifice, selfdenial and sometimes even martyrdom. The ministry of Christian diaconia ministers to the 12 Christian community and to all who come within range of its knowledge and loving care. The object of Christian diaconia is to overcome evil, by offering deliverance from oppression and injustice. For this reason, diaconia is an essential element that sustains the life and growth of the church (Ecumenical documents nd:176,177). Nordstokke (2014:67,68) has suggested a new approach to the search for diaconal motifs and messages, with a vital focus on the sequence of seven narratives that John presents as signs (shmeion) in chapters 2-11 of John’s Gospel. Nordstokke reads these signs as diaconal signs, both in the sense that they let us see the diaconal ministry of Jesus and at the same time as signs for our diaconal practice today. The following are the seven signs: The wedding at Cana (2:1–12); Jesus’ healing of an official’s son (4:46–54); Jesus’ healing of the sick at Bethesda (5:1–18); the feeding of the five thousand (6:1–15); Jesus’ walking on the water (6:16–21); the restoration of sight to a man born blind (9:1–41); and Jesus’ raising of Lazarus to life (11:1–44). These signs in Nordstokke’s view connect faith and life – faith in Jesus, the one who did the signs, and life reflecting their everyday experience of vulnerability and suffering. This is why Nordstokke believes that the narratives of the signs can be read in a diaconal perspective. Each of them takes place in the midst of human reality, they present stories of marginalized people, and how forces of death threaten their life (Nordstokke 2014:67,68). I will argue in the remaining part of the paper that through the concept of Christian diaconia, the Christian community in Nigeria and other parts of Africa could effectively mobilise its resources to minister to its fold now facing death, persecution, oppression, intimidation, marginalisation and other forms of injustice. Through the same concept the church could even in the mist of its own pain and suffering fulfil its very nature as creation carer and God’s agent by ministering to non-Christians and the agents of terror, their families and communities. In the same vain, issues of poverty, underdevelopment, corruption, unemployment, diseases and other forms of suffering have become perennial in the Nigerian society and elsewhere, the church’s calling places an obligation on it to respond to these needs. In the light of the above, the concept of Christian diaconia offers the Nigerian Christian community in particular a vital ecclesial paradigm that if properly engaged within the ecumenical, denominational, congregational and individual level could assist the Christian 13 community in ministering to the needs of the members of the community and to the larger society. Without undermining the enormous task of fulfilling such an ambitious endeavour in the Nigerian society given the religious, socio-political and economic challenges being posed by Boko Haram, such a diaconal ministry could assist in fostering neighbourly love, building of inclusive communities, caring for creation and struggling for justice. These components that are integral to the nature of the church and its diaconal ministry are needed now more than ever in the Nigerian society. Diaconia of neighbourly love The diaconia of neighbourly love requires transforming faith into action. This process requires asking time and again, “who is my neighbour?” (Luke 10:29-37). It also involves individual Christians and Christian communities placing themselves at the disposal of the marginalised, the persecuted, the suffering, the hungry, the thirsty, the sick/wounded and the stranger (Muslim, enemy or terrorist) by asking the question: What do you want me to do for you? (Matthew 25:35-46) (Church of Norway nd:7). Loving and caring for our neighbour involves our whole being and should be based on reciprocity, equality and respect for the integrity of the other. The mutual dependence of human beings requires that throughout life humans should be met with love and compassion. The practical show of love and compassion may sometimes involve small, simple acts. It may also involve major and demanding efforts (Church of Norway nd:7,13). Aarhus Johannes Nissen (2014:39) has pointed out that the manifestation of neighbourly love in the story of the Good Samaritan could only be possible through seeing, having compassion and acting. What this means is that it is not sufficient to detect those who are suffering by studying statistics or reports of suffering people. Since these persons are flesh and blood (real people), the weight of their real conditions can only be more appreciated by seeing with our own eyes. Secondly, the experiences of the suffering requires more than pity, it requires compassion. Compassion goes far beyond pity; it bridges the gap between perception and effective action. Thirdly, the Samaritan “went to him” (the afflicted). It could thus be noted that it was only when all the tree actions were carried out that the Samaritan was able to do what he did. The diaconia of neighbourly love calls for the Christian church in Nigeria through its ecumenical, denominational, congregational and individual capacities to respond to the 14 challenges of all persons being affected by the acts of terror by Boko Haram and other forms of militant Islam. Such persons include Christians, non-Christians, Muslims, members of Boko Haram and their supporters. Such a diaconia requires the specialised ministry of deacons (ordained and non-ordained) and other volunteers drawn from all over Nigeria and beyond with skills and provisions that can assist them to minister to the needs of the afflicted. It requires that these “deacons” visit the places and persons being affected. It is also crucial that the diaconia of neighbourly love be inculcated into all Christians and the practice of it should become the Christian lifestyle. Such a lifestyle could assist in building inclusive communities. Building inclusive communities through Christian diaconia The Christian community is fundamentally an inclusive community marked by hospitality (Johannes Nissen 2014:41) which has the potential of transmitting its nature to the larger society. The notion of building an inclusive community implies that there are persons that are outside of the community by some reasons which may be cultural, religious, gender, sociopolitical or economic. Such persons are seen as “strangers”. Johannes Nissen (2014:42) has therefore argued that in today’s context the “stranger” includes not only the people unknown to us, the poor and the exploited, but also those who are ethnically, culturally and religiously “others” to us. He further argues that the biblical notion of “stranger” does not intend to objectify the “other,” but there are people who are truly “strangers” to us in their culture, religion, race, and other kinds of diversities that are part of the human community. The willingness of the Christian community to accept others in their “otherness” is the hallmark of true hospitality and a pertinent step towards building inclusive communities. In a context such as Nigeria where religious, ethnic, socio-political and economic divisions are deeply entrenched, building inclusive communities has become indispensable. The challenge of religious otherness between Muslims and Christians is the main driver of terrorism and its consequences. The evident suspicion and hate between religious and ethnic groups is a reflection of an un-inclusive society. But the same suspicion and hate also exists between the rich and the poor and in some instances between the ruler and the ruled. It is also possible that there could be a grand standing on the part of a particular religious or terrorist group which may make it very difficult to realise the vision of an inclusive society. In addition, the pains of the past years of attacks and retaliation, betrayals and broken promises could contribute to the difficulty. 15 Whilst the scenarios above cannot be ignored and as such deserves much reflection, it is pertinent to note that an important item of Christian teaching is that we are created to live in fellowship with one another. It is therefore a diaconal responsibility to strengthen relationships between people and to establish new ones when existing relationships break up. Some of the important component s of healthy communities is that they are diverse, inclusive and they offer everyone the opportunity to give and to receive (Church of Norway Plan nd:16-18). For the grace of God manifested in Christ calls the Christian to an attitude of hospitality that is not limited to those who belong to the same group but extends to loving even the enemies ( Johannes Nissen 2014:44).To successfully carry out a diaconia of building inclusive communities, justice and reconciliation are crucial. Diaconia of justice and reconciliation Justice and reconciliation are inseparable. Every human being is entitled to a life of dignity which includes safety, peace, self-actualisation and other fundamental human rights. In a society where there is wanton killing of human beings by terrorists, security agents and persons who claim self-defence, the church must show solidarity and join all persons experiencing injustice in the struggle for justice. The diaconia of justice does not show indifference to people who are fighting for their life. It must ensure that human life must be protected from conception to the grave. In fulfilling the diaconia of justice, the church must be a critical voice against all manifestations of injustice and must also meet the challenges posed by these issues through programmes and projects (Church of Norway n.d:20). The diaconia of justice which should be focused on addressing issues of injustice through programmes and projects must begin from the Christian community and should flow into the wider society. The early Christians aimed at constructing a community which in itself was an example of a just society (Johannes Nissen 2014:45). In this regard, a diaconia of justice must work for the just distribution of the world’s resources among Christians and the larger society within the local context and beyond, through financial support by donor agencies and empowerment schemes. Such a diaconia will also support people whose dignity is violated through pastoral care, awareness campaigns, support groups, etc. Such endeavours should also be accompanied by non-violence, peace, reconciliation, legal actions against perpetrators of injustice and preventive measures. 16 Reconciliation is an on-going process aimed at overcoming estrangement. It is rapprochement in-depth as a result of conversation, argument, discussion and debate (Higginson 2009:44). Reconciliation is about transforming dehumanising situations and their personal and social consequences. Social reconciliation is only possible when a community recovers its dignity and honour. It requires that the human rights abuses are brought to light so that victims can tell their stories, be heard, grieve and gain the support of their communities, and for the perpetrators to admit to their abuses. According to Beyers Naude (1991:227), “No healing is possible without reconciliation, and no reconciliation is possible without justice, and no justice is possible without some form of genuine restitution”. In Nigeria, diaconia of justice and reconciliation must begin within the Christian fold and their respective ethnic groups and must progress to the adherents of Islam and ultimately to the groups of militant Islam. An approach to reconciliation and justice directed at the Christian community itself will deal with issues pertaining to denominational differences and ethnic suspicions which are deeply entrenched in the Nigerian society. The diaconia of justice and reconciliation can then proceed to the adherents of Islam and Islamic militant groups. Christian diaconia of justice and reconciliation will have to build synergy with government and civil society (Higginson 2009) to ensure adequate security for Christians and other vulnerable persons. By engaging ecclesial institutional power in tandem with government, the Christian diaconia of justice and reconciliation will have to ensure that government fulfils its responsibility of protecting its citizens from terrorism and intimidation (Romans 13:3). In the same vein, diaconial collaboration with civil society through the institutional power of the church will ensure that publicity is made and civil actions will be engaged to bring to the notice of the Nigerian society and beyond all forms of threats and actions that are tantamount to human rights abuses against Christians. Where the church feels the government and its security operatives cannot or is failing to protect Christians from terrorists, the church’s diaconia of justice should be at liberty to explore responsible measures that can assist Christians to obtain security services for their lives and property. Christians like other citizens have a right to self-defence where they face conditions that perpetually place them in danger and insecurity (Higginson 2009). As an important component of the Christian diaconia of justice, all Christians serving in executive, legislative, judiciary and security/military arms of government must be encouraged to be sensitive to the security situation of the nation and must be committed to their responsibilities to the state and the Christian community. 17 Conclusion The struggle of African Christian communities to combat poverty and religious violence in their respective contexts is enormous and frightening. In the end, the church may be well-off or worse-off depending on her approach to the crisis. The response of the Nigerian church in its various expressions, so far although commendable, still lacks the capacity to contain the crisis, enable the healing and flourishing of the church and Nigerian society, and forestall the emergence of such crisis in the future. A creative strategy that is theologically and ideologically embedded in the very nature of the church has become inevitable. Such a strategy must incorporate the present mode of the churches engagement but must also assist the church to go beyond its present scope. The new strategy suggested in this paper includes the deliberate use of the concept of Christian diaconia through the diaconia of neighbourly love, building of inclusive communities and struggling for justice and reconciliation through the institutional church, its individual members in their respective professions and collaborative networks with relevant institutions locally and internationally. Such strategy of Christian engagement in contemporary Nigeria and other parts of Africa could mitigate the impact of the crisis of poverty and religious violence to the benefit of Christians, Muslims and the entire Nigerian and other African societies. Works cited Aarhus, JN. 2014. Creating a space for the others: the marginalised as a challenge to Diaconia and church- a theological perspective, Diaconia, (5), 31–46. Abubakar, M.S. 2010. ‘You and your Muslim neighbour’, Paper presented at a seminar of the National Executive Committee (NEC) of the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN), Abuja, 20 March. Agbiboa, D. E. 2013. The Nigerian burden: religious identity, conflict and the current terrorism of Boko Haram, Conflict Security & Development, (13):1, 1-29, DOI:10.1080/14678802.2013.770257. Agbiji, O.M. 2012. Development-oriented church leadership in post-military Nigeria: A sustainable transformational approach, PhD dissertation, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch. http://hdl.handle.net/10019.1/71734. America, 2004. ‘Nigerian bishops plead for peace and dialogue’, America: The National Catholic Review, 7-14 June, 6, viewed 24 January 2011, from http://business.highbeam.com/410107/article-1G1-119186151/nigerian-bishops-pleadpeace-and-dialogue. Carson, J. 2012. “US Official: Violence in Nigeria isn’t about religion”, Daily Trust (print edition), 6 April 2012, 29. Cavanaugh, W. T. 2009. The myth of religious violence: Secular ideology and the roots of modern conflict. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 18 Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN). 1988. ‘Communique of 2nd General Assembly’, in A.O. Makozi & G.J.A. Ojo (eds.), Religion in a secular state: Proceedings of the Second Assembly of the Christian Association of Nigeria, pp. 48-50, CAN, Abuja. Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN). 2004. Constitution of the Christian Association of Nigeria, CAN, Abuja. Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN). 2010. Brief story of the Christian Association of Nigeria, CAN, Abuja. Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN). 2012. ‘Christian Association of Nigeria gives final call to Federal Government on violence against Christians’, viewed 7 February 2014, from http://cannigeria.org/christians-association-of-nigeria-gives-final-call-to-federalgovt-on-violence-against-christains/. Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN). 2014a. ‘CAN tasks politicians on tolerance, peace in 2014’, viewed 3 March 2014, from http://www.informationng.com/tag/christianassociation-of-nigeria. Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN). 2014b. ‘Leaders should be elected based on competence, not religion – CAN’, viewed 3 March 2014, from http://www.informationng.com/tag/christian-association-of-nigeria. Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN). 2014c. ‘CAN youth wing decries recent killing of students in Yobe’, viewed 3 March 2014, from http://www.informationng.com/tag/christian-association-of-nigeria. Church of Norway National Council. Church of Norway plan for diakonia. Oslo: Church of Norway Information Service, viewed 19 August 2014, from http://www.kirken.no/english/doc/engelsk/Plan_diakonia2_english.pdf. Ecumenical Document. 2014. Church and service: An Orthodox approach to diaconia. Graybill, L. S. 1995. Religion and resistance politics in South Africa. Westport: Praeger. Harnischfeger, J. 2014. Boko Haram and its Muslim critics: Observations from Yobe State in de Montclos, M (ed). Boko Haram: Islamism, politics, security and the state in Nigeria, 33-62, viewed 22 August 2014, from https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/23853/ASC-075287668-344101.pdf?sequence=2. Higginson, F. C. 2009. Diakonia as a case study in Christian non-violent social action for peace and social justice in South Africa 1976-1982, MA dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, KwaZulu-Natal. Human Rights Watch Report (HRW). 2012. Spiralling violence: Boko Haram attacks and security force abuses in Nigeria viewed 22 August 2014, from http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/nigeria1012webwcover_0.pdf. Huovinen, E. 1994. Diaconia – a basic task of the Church. Pro Ecclesia (3):2. 206-214. Kwashi, B. 2004. Conflict, suffering and peace in Nigeria. Transformation Journal, 21(1): 60–69. Mang, H. G. 2014. Christian perceptions of Islam and society in relation to Boko Haram and recent events in Jos and northern Nigeria in de Montclos, M (ed). Boko Haram: Islamism, politics, security and the state in Nigeria, 85-109, viewed 22 August 2014, 19 from https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/23853/ASC-0752876683441-01.pdf?sequence=2. Mohammed, K. 2014. The Message and methods of Boko Haram in de Montclos, M (ed). Boko Haram: Islamism, politics, security and the state in Nigeria, 9-32, viewed 22 August 2014, from https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/23853/ASC-075287668-344101.pdf?sequence=2. Naude, B. 1991. “The role of the Church in a changing South Africa”, in L. Alberts et al (eds). Nordstokke, K. 2014. Diakonia according to the Gospel of John, Diaconia, (5), 65–76. Olojo, A. 2013. Nigeria’s troubled North: Interrogating the drivers of public support for Boko Haram, viewed 5 August 2014, from http://www.icct.nl/download/file/ICCT-OlojoNigerias-Troubled-North-October-2013.pdf. Onaiyekan, J. 2010. ‘Dividends of religion in Nigeria’, Unpublished public lecture presented at the University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria, 12 May. Otubu, J. 2014. Church leader urges prayers to tackle Boko Haram, insecurity viewed 21 August 2014, fromhttp://allafrica.com/stories/201408200452.html. Popular Discourses of Salafi Radicalism and Salafi Counter-radicalism in Nigeria: A case study of Boko Haram. 2012. Journal of Religion in Africa 42. 118-144. Smart, N. 1996. Dimensions of the sacred: An anatomy of the world’s beliefs. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Swart, I. 2006. The churches and the development debate: Perspectives on a fourth generation approach, SUN Press, Stellenbosch. Williams, C.O. 1988. ‘General Secretary’s report’, in A.O. Makozi & G.J.A. Ojo (eds.), Religion in a secular state: Proceedings of the Second Assembly of the Christian Association of Nigeria, 10-12, CAN, Abuja. Zaimov, S. 2014. Nigeria: 4 Churches Burned Down, Scores Killed in Deadly Boko Haram Attack on Christians, viewed 21 August 2014, from http://www.christianpost.com/news/nigeria-4-churches-burned-down-scores-killed-indeadly-boko-haram-attack-on-christians-122439/#!. Zenn, J. 2014. Leadership analysis of Boko Haram and Ansaru in Nigeria. CTC Sentinel (7):2. 23-29. 20