A study of phenomenology and typology as might be applied for use

advertisement

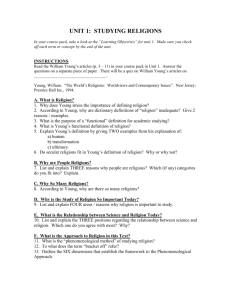

SESSION 9A. PHENOMENOLOGY AND TYPOLOGY Introduction Phenomenology describes an approach to the study of religion as a means of gaining greater understanding of human experience and of the world in which we live, without a confessional or evangelising intention. A phenomenological approach to the study of religion includes observation, description, the suspension of preconceived judgment, and imaginative and empathetic participation in the world of the believer, in order to come to understand something of the world’s religious traditions. In this module we first describe the significant contribution phenomenology has made to theory in religious education, note certain controversies that have surrounded it and then claim that in a time riven by religious misunderstanding and intolerance, it remains central to any discussion of religious education theory. The background Up until the 1970s, discourses about religious education were generally theological and ecclesial, and were to a large extent, conducted by and within Christian traditions. During the twentieth century, however, the progress of globalisation and patterns of migration to Western countries meant not only that the cultural composition of these countries changed, but also that they became home to a wide variety of religions and cultural expressions of these religions. Theories of religious education that assumed Christianity as foundational, or even that were biased for one form of religious expression over another, became increasingly ill suited to multi-religious societies and school systems. Religious educators, scholars and academics in Britain led the “religious studies” movement, that expanded the field of theory in religious education beyond the domination of the Christian tradition. Like all significant changes in education, the development of a new theory of religious education suited to multi-religious schools was gradual. The Butler Act of 1944 in England had made religious education compulsory in all county schools, and it was to be taught using an “agreed syllabus” that would be developed under the authority of the Local Education Authority by all of the religious groups represented in the local area. Hull (1984) has documented the history of the agreed syllabi, showing that up to 1964 they concentrated on study of the past, particularly through the Bible and examples of exemplary Christian life. In the later 1960s, the agreed syllabi revealed more understanding of the experiential dimension of religious education, but these still saw religious education essentially as education in and about Christianity. Hull (1984, p. 80) illustrated the changes that were coming when he quoted from the first of the syllabi to attend to the multi-religious nature of the British community, the Bath Agreed Syllabus of 1970, that the primary aim of religious education was to help young people to understand the nature of religion. The city of Birmingham was the first to develop a religious education syllabus that took account of the multi-religious nature of its population, allowing for breadth of studies of religions as they were represented in the local community, and also for a particular study of one religion if the population of the school required this. The revised Birmingham Syllabus of 1970 was extremely significant for its commitment to “ a religious education syllabus that would make a positive contribution to community relations in the city” (Hull, 1984, p. 87), and for the fact that there was a distinction made between the personal religious convictions of the teacher and the syllabus content. The Birmingham syllabus could be taught by any “well informed teacher of good will, regardless of his faith, to any interested pupils, regardless of their faith” (Hull, 1984, p. 88). It was intended to develop a critical but tolerant understanding of religion in a modern secular content, and its approach was descriptive and existential. Hull observed that after the Birmingham syllabus, the agreed syllabi were never as influential as they had been, but he claimed that they gave “official approval and recognition to trends already established” and registered “the climate of the subject and set out its norms” (1984, p. 91). Consider What condition in state schools in England suggested that an objective study of religion was more suited to state school religious studies than an approach that focuses on Christianity? Are there any parallels in your teaching context? Phenomenology These trends and the climate of religious education in Britain in the 60s and 70s were significantly influenced by the work of Ninian Smart (1968, 1974, 1976, 1978,) who advocated the study of religion as a means of gaining greater understanding of human experience and of the world in which we live, without “interest in or intention of evangelising” (Lovat, 1995, p. 1). The sociologist of religion, Durkheim (1976), had argued for the “scientific or rational” (Nisbet, 1976, v,) study of religion, applying scientific analysis to its origins, development, and practice from the perspective of an independent observer. The purpose of this was to gain insights into religion as a whole, its history, its nature and its relationship to other phenomena in human life. Smart took up this emphasis, and developed a phenomenological approach to the study of religion drawing on the philosophy of Husserl (1983). Husserl’s philosophy of phenomenology began from the fact of the human being surrounded by a world full of “corporeal, physical things” (1983, p. 51), animate and inanimate, which are present to human consciousness or, if unheeded, present to intuition. Each of these has its own actuality independent of one’s perception of it. They include objects, but also ideas, experiences, traditions, values, other people; in fact the entire range of objects of human experience and perception. These objects or “phenomena” furnish the individual’s conscious and semi-conscious worlds. In my waking consciousness I find myself in this manner at all times, and without ever being able to alter the fact, in relation to the world which remains one and the same, though changing with respect to the composition of its contents. It is continually “on hand “ for me and I myself am a member of it. (Husserl, 1983, p. 53). Any apprehension of experience and the world must begin with the “the natural standpoint, from the world as it confronts us” (Husserl, 1983, xix). This apprehension of the world, however, involves eidetic judgments, or judgments about the essential nature of the objects within it. These eidetic judgments lead, through description, comparison and analysis to identification of universal phenomena within which the individual essences cohere. “Any judgment about essences can be converted into an equivalent unconditionally universal judgment about single particulars”. (p. 13). The reduction of individual phenomena into phenomenological universals leads to discovery of the complex relationships between these universals. . Good eidetic judgments about individual phenomena, and the consequent classification of these as examples of universal phenomena, require “epoche”, or suspension by the observer of all preconceptions, so that phenomena may be seen for what they are. This involves firstly a conscious “bracketing” (Habel & Moore, 1982) of empirical preconceptions, (which cause the observer too often to come to hasty conclusions about phenomena), so that we may neutrally and objectively see “what stands before our eyes” (Husserl, 1958, p. 43). Secondly, it involves a suspension of preoccupation with facts, to see through the phenomenon being observed to encounter its essence, the pure phenomenon. The phenomenologist therefore must learn to put aside preconceptions about what they observe, and not be distracted by the outward form of the phenomenon, in order to look to its pure essence, classify it within a universal phenomenon, and perhaps extract personal meaning from it. The phenomenologist is first a detached observer of phenomena, for the purpose of identifying their essence, finding the dissonances and coherence between them, reducing multiple phenomena to broader universal phenomena, seeing the relationships between universal phenomena so that patterns of experience and meaning may be uncovered. Consider Although it can seem complex, phenomenology is really concerned with seeing things as they are, or as they stand before our eyes, without making judgments about them or allowing our own experience to cloud our view. Why might objectivity sometimes be a good thing in relation to the study of religion? Phenomenology and Religion In 1958 Otto's The Idea of the Holy had claimed that religious consciousness or awareness of the numinous or the sacred existed a priori in the human experience. That is not that everyone is religiously conscious, but that everyone is capable of being so. It is a capacity of human nature which “issues from the deepest foundation of cognitive apprehension that the soul possesses,” and which must be awakened. “It does not arise out of [the data of the natural world] but only by their means” (Otto, 1958, p. 112). That there are ‘predispositions’ of this sort in individuals no one can deny who has given serious study to the history of religion. They are seen as propensities predestining the individual to religion, and they may grow spontaneously to quasiinstinctive presentiments, uneasy seeking and groping, yearning and longing, and become a religious impulsion which only finds peace when it has become clear to itself and attained its goal (Otto, 1958, p. 115). Predisposition to the numinous or religious consciousness has an a priori existence within the human mind, and is manifested in history in outward behaviours, values, attitudes, beliefs, which are not intrinsic to the predisposition but differently and in different historical contexts allow the person to express it. According to Otto, the phenomenon of religious consciousness, as well as the many phenomena through which it is manifested in history, may be studied, as they exist, through description and rigorous analysis. This may uncover patterns of meaning, and ultimately bring the student at least to knowledge of key images of, if not experience of, the “entity” that is at the heart of religious consciousness. Consider In other words, according to Otto, religious experience and its expression is a phenomenon that can be objectively studied. What do you think about this proposition? Studying Religious Phenomena: Observation The philosophies of Husserl and Otto helped to lead to the development of the philosophy of the study of religious phenomena, (Eliade, 1958; Hick, 1991) and to the work of Ninian Smart who was concerned with “trying to exhibit religion and religions through uncovering the anatomy of Religion” (1973, p. 52). The following sections of this chapter illustrate Smart’s phenomenological method in regard to the study of religion, and the final sections review contemporary critique of the method. The first step in the phenomenology of religion is simply to plunge into observation and experience of religious phenomena, bracketing one’s own experience, preconceptions and beliefs in order to experience and learn about the phenomenon in an unbiased way. Depending on the phenomenon being studied, this will involve all of the senses in collecting data about the object of study. This is well illustrated in numerous examples given in the BBC series The Long Search (1979). This series of documentaries illustrated Smart’s phenomenological method for the study of religion, and involved the presenter Ronald Eyre in a three-year investigation of religious phenomena around the world. Examples were drawn from ancient and modern, as well as local and diffused religions (Lovat, 1995, p. 9; 2002, p. 45). In one series of episodes Eyre was shown at St. Peter’s Square in Rome, and later within St. Peter’s Basilica, observing the splendour of a papal Mass. In a related episode he stayed with a group of young religious brothers who lived in simplicity in a village in the desert, shared their lives with the local people, and celebrated daily the same ritual that Eyre saw celebrated in St. Peter’s Basilica. Eyre’s investigation was, to use a contemporary colloquialism, “hands on”. He did not give long descriptions or historical summaries, but entered into the story, ritual symbol or other phenomenon with the believer in order to understand it. He approached the investigation as an outsider, and did not bring to it any judgments that may have obstructed his ability to “see what is before his eyes”. In both instances noted above Eyre observed and listened, asked many questions and used whatever other means were appropriate to gather data about the phenomenon. View the video extract and mail to the discussion board some comments on the methodology you see there. INSERT EXTRACT FROM THE VIDEO THE LONG SEARCH Stepping Into the Shoes of the Believer This almost clinical gathering of data, however, is only the first step. In the words of Smart: But religion is not something that one can see. The significance needs to be approached through the inner life of those who use the externals. The history of religion must be more than the chronicling of events. It must be an attempt to enter into the meanings of those events. So it is not enough to survey the course which the religious history of mankind has taken, it must also penetrate into the hearts and minds of those who have been involved in that history (Smart, 1976). For Smart, while learning about and coming to understand something of a religious phenomenon did not involve adopting the belief system of the religion to which the phenomenon belonged, it did require “imaginative participation’ (Smart, 1974, p. 3) in the world of the believer. The phenomenologist must “step into the shoes” of a believer in order to see the phenomenon through their eyes, and thus come to understand something of its significance. In The Long Search Eyre witnessed funerals and initiation rituals, talked to believers about their beliefs, participated when invited and always described what was evident to his senses, as well as raising his own thoughts, feelings and questions about the phenomenon. This “stepping into the shoes” of the believer represented for Smart the intuitive side of religious studies, the side that deals with what a phenomenon means. Thus, after his stay with the brothers in the desert, Eyre reflected on what he had seen heard and experienced, and on the reasons why young men might take up this lifestyle. He distilled the meaning of the experience for himself, through appropriating the knowledge in a critical way, assessing its meaning for himself, “picking the eyes out" (Habel & Moore, 1982) of the knowledge in order to gain some personal learning. This is the eidetic aspect of the study of religion, and it can only be done after the religious phenomenon has been fully investigated, analysed and described objectively (Lovat, 2002, p. 89). The “judicial and critical assessment” that comes after the description of the phenomenon is Husserl's "eidetic science”, the effort to get to the heart or the essence of the phenomenon, and it is absolutely essential to the use of the method. As Lovat points out (2002, p. 88), those who criticise the phenomenological study of religious as dry, clinical, over-cognitive and relying on an unrealistic putting aside of one’s own judgment have only understood its first step. The intuitive aspect follows the objective observation and description, and it is here that the student appropriates the knowledge that has been gained in a way that is reflective and critical, and that allows personal meaning to be drawn from it. In a later paper Lovat even claimed that this intuitive, subjective dimension of the phenomenology of religions could allow for the discussion of personal religious commitment (Lovat, 2005). Consider How do you see the external aspects of religion and the internal aspects working together in the phenomenological approach to the study of religion? B Classifying Individual Phenomena into Universal Categories. While Smart saw religions as whole systems that communicate meaning, he identified six dimensions that could be found in religions, and that could be used as the basis of comparison and contrast between them. These dimensions were mythological, ritual, doctrinal, social, ethical and experiential. Each dimension has many layers. The mythological dimension, for example, represents all types of sacred stories and includes myths, legends, parables, and epics. The ritual dimension represents the many varieties of rituals celebrated in religions throughout the life cycle, including rites of passage, communication, cleansing and thanksgiving. The social dimension includes all of the ways in which a religion is organised, its social structure, history and relationships with the cultures in which it exists. It includes sacred space, sacred time, sacred persons and roles, especially as they relate to stories and rituals. The doctrinal dimension refers to the many different forms of beliefs that religions hold, including beliefs about the nature of deities, about the world and about the afterlife. The experiential refers to the many forms and varieties of religious experiences, such as revelations, numinous experiences, ecstasy and many others ways in which people experience the sacred. The ethical dimension covers the laws of a religion and the values that are inherent in these laws. While the dimensions are differentiated for the purpose of identification and classification, the links between them are more important. Ritual, for example, is founded upon sacred story, makes use of social structure, expresses and communicates key beliefs, is based first upon an initial religious experience and makes possible religious experience for those who participate in the ritual. When individual phenomena have been subjected to observation, listening and, in the case of physical objects, handled if possible, and after consideration has been given to their meaning for the believer, the phenomenon many be classified into its wider dimension. For example, the Christian belief in God as Trinity belongs to the doctrinal dimension of religion, just as does the Hindu belief in Brahman and his many manifestations, just as does the foundational belief of Islam, the shahada: I testify that there is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his servant and messenger. The Buddhist belief in nirvana may be put alongside Christian and Muslim beliefs about the last judgment and paradise, and classified as beliefs about life after death. Thus each phenomenon is seen within its wider context, is able to be compared and contrasted with other phenomena of the same type and discloses patterns across religions that help students to understand much more fully and deeply the phenomenon we call religion. This study can lead to personal reflection about whether the patterns that are obvious in religious traditions across time and space are anthropologically grounded; about whether they point to a capacity for attentiveness to the sacred that is innate in human nature, and even about whether the patterns through which this is expressed are biologically determined. The student of the phenomenology of religion is brought into the worldwide experience of religion with all that it has the potential to bring to the individual’s search for personal meaning. Summarise have learned so far about the phenomenological approach to the study of religion. What application can you see for it in your context? Habel and Moore (1982) and Typology. Two Australian scholars, Habel and Moore, saw the potential of Smart's phenomenology of religion for religious education. Because Smart had not designed a practical way in which phenomenology could be used with children and young people in the classroom, they set out to develop it into a religious education method. Using Smart’s five dimensions of religions as the starting point, they identified eight “types” as the “building blocks” or fundamental elements of religions. Initial knowledge of these types—beliefs, sacred stories, sacred texts, rituals, social structure, symbols, ethics, religious experience— would give the students a language or a map through which religions may be studied. The types are the keys to learning about religion, just as words are the keys to literacy and numbers the keys to numeracy (Lovat, 2002). A further aspect of typology is that while it is cross cultural, intending that students learn about a range of religious traditions and phenomena within them, it begins with the home tradition, that is, the religious tradition with which the student is most familiar. Only when a phenomenon has been identified within the home tradition is it taken into a broader context and shown against other examples of the type. A religious education class in a Jewish school, therefore, may begin with the story of the journey of Moses and the people from Egypt across the desert to the Promised Land (Exodus 3–24). The story would first be studied in its own right, seen in its historical, geographical and social contexts, identified within the sacred text, its elements explored and listed. Next the story would be classified as a sacred legend, and particularly as one with a journey motif. Other forms of journey stories would be read, some secular, but many from religious traditions. The journey of Jesus into the desert from Christianity (Mark 1:12–14) may be used, as may the journey of Mohammed to Medina, or the journey of the Buddha out into the world. Examples of similar stories may also be drawn from local tribal religions. The elements of the stories are listed and compared, so that the original story of Moses and the peoples’ journey through the desert is shown against the patterns of the other stories, and similarities and differences are noted. Finally the original story, having been studied in the wider context, is brought back into the home tradition, and its significance in relation to the other elements—for example, its place as a foundation of ritual—is shown. In the final step, students are encouraged to reflect on the meaning of the story, both for participants in the home tradition and for themselves. Take another religious education topic and try to develop in the typological model given above. The Impact of Phenomenology on Religious Education Curricula. The phenomenological approach to the study of religion has been extremely influential in Britain, Europe and Australia, where it has presented a non-judgmental way of studying religions as phenomena of human existence, and thus of contributing to greater understanding and tolerance of the religious groups within a local community. In Britain, Grimmitt (1973, 1987, 2000) argued for greater attention to the purpose of religion as the search for meaning, and his work has helped teachers to use religious phenomena to encourage students to explore ultimate questions. In Australia during the 1980s all states developed education acts which included in their recommendations that state schools attend to the study of religion in an objective but sympathetic way, an activity which, it was hoped, would developed greater understanding and tolerance of religious groups in the increasingly religiously diverse Australian community. By the late 1980s and early 1990s (with the exception of South Australia which had had a religious studies subject for state schools since the 1970s) all Australian states had introduced into their senior secondary curriculum elective religious studies units based on the phenomenological method. Typically these deal with issues of religion and identity, roles and rituals in religions, the experiences of religious believers within their traditions, ethics, past and present challenges to religious traditions and religious beliefs in action. While the studies have been enthusiastically embraced by Catholic schools, they have also been taken up by other Christian, Jewish and Muslim schools and, to a lesser but growing degree, by state schools. Writing of the similar reception the New South Wales Studies in Religion curriculum had received, Lovat attests the “cleverness” of phenomenology: The capacity of a subject to function in such diverse settings and clearly be seen as contributing to the ethos of such different kinds of schools says much in my view about the flexibility and unique cleverness of phenomenology as a method (Lovat 2005, p. 46). The influence of phenomenology on religious education curricula in Australia however has not stopped there. All Christian schools now include studies of other religions in their religious education curricula, and as schools revise their religious education curricula a more educational focus may be seen. While this owes much to a more sophisticated discourse about religious education among Christian schools in Australia, it has also developed, in the opinion of this author, from the successful presence of the phenomenological approach in the state based courses in the senior school certificate. What are the titles of the state based senior secondary religious studies units in your state, and what are some of the topics they cover? THE FOLLOWING SECTION IS OPTIONAL. IT WILL PROVIDE EXTENDED READING AND CRITIQUE FOR THOSE WHO WISH TO FOCUS ON THIS MODULE FOR ASSESSMENT. THOSE WHO DO NOT WISH TO DO THIS SHOULD GO TO THE CONCLUDING PARAGRAPH. Controversy About Phenomenology as a Method for Religious Education During 2001 a debate was conducted in the journal Religious Education between Terence Lovat (2001), an Australian scholar and proponent of a phenomenological method in religious education, and Philip Barnes of the University of Ulster (2001, 2001a) who wrote in the context of the British education system, where the method of phenomenology in the study of religion was widespread. Barnes began his critique with a review of a 1988 debate in the House of Lords, where Christian groups had successfully lobbied for Christianity to be privileged in agreed syllabi, because Christian traditions were in the majority in the community. Barnes showed how the debate quickly became ideological, with an increasingly conservative Christian lobby attempting to assert Christian supremacy and marginalise adherents of other religions, while those who advocated phenomenology contented themselves with exposing the prejudices of their opponents, and appropriating the moral high ground of tolerance, openness, autonomy and social justice. After his careful description of the phenomenological approach to the study of religions that followed his review of the debate, Barnes attempted to raise what he considered were the critical issues that surrounded the use of phenomenology as a method in religious education. He claimed that the assumptions that underlie phenomenology of religion—that is, that there is an essence of religion, that this essence is experienced in religious consciousness, and that there is a dichotomy between religious experience and the language used to describe it—can no longer be held. He challenged the basic premises of phenomenology, that the heart of religion is located in the experiential self, that the stories, rituals, language and symbols that express it in the world are distinct from this consciousness, and that religious consciousness extends far deeper than, and well beyond, these phenomena. Barnes (2001) summarised the phenomenological method in religious education in these words. In studying religious founders or holy places, or sacred acts, one is being prepared for the moment of encounter with the Sacred. Education can only point. It can take one to the threshold of experience. It pauses at the door of the Holy—those who proceed further enter into the heart of religion and subsequently come to speak, however imperfectly, of the mystery encountered (Leech, 1989, cited in Barnes, 2001). In the distinction made between religious awareness and conceptual thought, Barnes argued, the phenomenologist of religion is able to avoid the controversial activity of assessing the truth claims of religions, since rival doctrinal expressions are just various expressions of the common religious consciousness. He claimed that phenomenology was now highly questionable, because its basic assumption that religious experience (consciousness) and the expression of this in religious language and concepts are separate, can no longer be held. He argued from the later philosophy of Wittgenstein (1958, 1969) that religious concepts and religious language, rather than being separate from religious experience, actually structure and condition it. Feelings, emotions and religious consciousnesses do not exist a priori but are dependent upon language and concepts for their existence. “Without the appropriate religious concepts and religious language there would be not religious experience”. (Barnes 2001, p. 456). The argument follows that if personal experience of the divine is structured and conditioned by the ways in which religions express it through the public symbols of faith, then both the privacy and universality of religious experience is questioned. Education should not just study how people express religion, but should also critique religions in terms of their validity and relevance. There is no privileged domain of introspective knowledge. Private experience is a function of public discourse, intrinsically dependent upon the latter. Understanding religion is not achieved by attempts to intuit its essence, but by coming to know its public discourse and by being able to enter into a world where that discourse is an expression and a part. The aim of religious education should be to advance and enable such an understanding (Barnes, 2001, p. 457). The essence of Barnes’ critique therefore was that phenomenology should be abandoned as a method in religious education, because it is founded on philosophical assumptions that are no longer tenable. There are no “religious truths too deep for words” (p. 458) that form the heart of religion. Religious consciousness is conceptually, linguistically and culturally bound and so is open to critique, a dimension of religious education that has been studiously avoided by phenomenologists. In response Lovat (2001) first observed that Barnes’ problem was perhaps not so much with phenomenology itself, but with the possibility of objective truth in regard to religion at all. Barnes critiqued phenomenology because of his perception that it claims an essentialist core to religion that is independent of the words, concepts and symbols used to express it, but Lovat argued that Barnes has overstated this dichotomy. If Husserl (1983) distinguished between the experience of a phenomenon and its language, concepts and symbols, this distinction had a methodological purpose. Husserl was concerned with the suspension of empirical judgment (epoche) about phenomena so that the essence they expressed could be more clearly seen. “Cleared of the pre-emptive judgments encouraged by empiricism, one can make a new set of judgments, formed by a more impartial, dispassionate, one might even say even-handed analysis” (Lovat, 2001, p. 565). Furthermore, Lovat argued, Husserl himself was not overly concerned with what is the burning issue for Barnes, the objectivity of essence. Whether the essence of a phenomenon is objectively factual or the product of culturally conditioned experience was not the main point of phenomenology. Husserls’ concern was simply for a different method of investigation, and his respect for Otto was not primarily because of Otto’s findings about the a priori nature of religious consciousness, but for the method Otto employed, the gathering of data after the careful suspension of his own views, and attention to precise description. The fact that Husserl promoted a methodology is, Lovat argued, an important point to which Barnes did not give sufficient attention, but this is the aspect of phenomenology that has led to its success as a method in religious education. Religious education teachers, after all, understand how pointless dogmatism is in education. They are also wary of the critical assessment of religious claims for which Barnes calls, for this closes off enquiry, pre-empts research and dialogue, and in any case is counterproductive in the multi-religious environment of the public school. Rather than close off enquiry through premature critique, Husserl's method encouraged suspension of judgment in the interests of growing in knowledge and understanding. Ultimately, philosophical debate notwithstanding (and Lovat argued that, far from being untenable, phenomenology takes in ancient [Aristotle, Aquinas] as well as modern philosophies [Habermas, 1972, 1974 and Eisner 1979]), Lovat argued that phenomenological religious education has been successful because it works. For the public school teacher of religion it provides a methodology that can be employed at some distance from the personal religious convictions of teacher and student. It does not enter into potentially divisive debates about religious truth claims, and in this neutrality it is able to promote religious literacy through open enquiry. Later in the same year, Barnes responded, again through the journal Religious Education, repeating his belief that the phenomenological approach to religious education was “deeply flawed” (Barnes, 2001a, p. 572), and that as a methodology it falsified religion by separating religious experience from religious doctrine, and giving greater priority to the former. In this, he argued, Liberal Protestantism had “won”. The Liberal Protestant synthesis of opposing religions and spiritualities is complete: religious truth is manifold yet ultimately one. The need for tolerance and understanding in our religiously plural world is transcended as ‘the other’ is discovered to be ultimately in agreement with ourselves’ (p.573). Here Barnes returned to his original argument, that debates about religious education in Britain had become ideological. While educationalists like Lovat may claim a particular methodology because it works politically and in practice, pragmatism is no excuse for allowing political, ideological or economic agendas to control the school curriculum. “Phenomenology effectively functions as a form of Liberal Protestant apologetics (even confessionalism); all the more insidious because it is unacknowledged” (p. 575). After arguing that the phenomenological method in religious education is ideologically founded, Barnes returned to his premise that phenomenology falsifies religion by putting religious experience first, and such expressions of religious experience as dogma only second. Barnes argued that an appreciation of religion is gained by first knowing religious concepts and language. Doctrines, beliefs and values facilitate religious experience, and these therefore should be the starting point of religious education. Furthermore, Barnes argued, the foundations of phenomenology, epoche and eidetic vision, are arguably beyond the capacity of children and young people in the school years. Ultimately he eschewed phenomenology as a method in religious education because it “refuses to address and explore the issue of religious truth: how is religious truth to be determined and what criteria are appropriate and so on? ” (p. 581). In essence, what were these debates about and what are your views? Some Responses to the Controversy The debate between Barnes and Lovat was enlightening, not just for its content but also for the way in which it was able to sharpen some of the issues that surround debates about religious education in general. The first of these issues is the extent to which any discussion about religious education can be free of ideology. Is Barnes less ideologically driven, for example, in his prioritising of religious doctrine over religious experience, than the Liberal Protestants he accuses of doing the opposite? Is he less ideologically driven than Lovat whom, he claimed, at least by implication, is the servant of expediency and political correctness? Ultimately an issue worthy of consideration is the extent to which any person’s history, religious convictions and views about the place of religion in life drive their approach to religious education curriculum. The problem is that when personal or community religious convictions collide with different traditions, no education is possible unless both parties are able to step back, put aside their own judgments and listen to each other. It is precisely this skill that phenomenology in religious education both teaches and insists upon. The skill does not favour confessional approaches to religious education, but even schools that have held rigidly confessional views about religious education (for example Catholic schools in this author’s home state) have come to see that dialogue about religion in a religiously diverse community is not advanced by taking an entrenched position, but by listening and empathy. These schools, too, understand that this is even more important at a time when some religious communities are being scapegoated for the activities of fanatical fringe groups that exist on the edges of their tradition. If nothing else, phenomenology can respond to the religious suspicion that is currently affecting the world community. I suspect that phenomenologists and the theorists of religious education represented by Barnes will never resolve the issue of which is central to religion, the experiential religious consciousness or the language, concepts doctrines which explain religion to the world. Methodologically, however, the distinction is important, and this is the second issue raised by the Barnes/Lovat debate. Generations of Catholics in the 1960s and 1970s (no doubt there was a similar pattern in other Christian Churches) began an exodus from the Church as it then was, because the dogma that they were expected to believe did not cohere with their religious experience. Today it is so much a given fact that young people trust in spiritual experience and pick and choose the vehicles they use to express this, that it is simply assumed in literature about young people’s spirituality. Crawford and Rossiter (1995) and Rossiter (1985) for example, among many Australian and international theorists (see also Engebretson, Rymarz & Fleming, 2002), have written of the “supermarket’ approach to religion taken by young people in Western secular countries. They express the inner experience of religious consciousness sometimes in beliefs flavoured by Buddhism, at other times in beliefs that are a mixture of Christianity and new age trends, and very few young people take on the whole package of a religious tradition. They prefer to choose elements from one or more traditions, or dismiss religious traditions altogether, asserting the primacy of personal spirituality. Whatever the personal religious convictions of the religious educator may be about the priority of doctrine over religious experience, the young people they teach have already voted with their feet. This brings me to the third issue raised by the debate, and that is the extent to which phenomenology is an appropriate method for young people whom Barnes claims may not have reached the Piagetian stage of cognitive development designated as “formal operations”. Are epoche and eidetic vision possible for them? Leaving aside the irony that it is these very young people (perhaps not capable of formal operations) whom Barnes wants to assess truth claims in religion, for an educationalist this question carries little weight. If Piaget’s stages of cognitive development are assumed (and not all educationalists uncritically accept them) formal operations theoretically should occur for most children in the early teenage years, making phenomenology at least appropriate for secondary school students. In Australia many thousands of young people have shown their ability to suspend their own judgment and to undertake the descriptions and analysis required by phenomenology in the state religious studies units, in large and increasing numbers. Although numbers enrolled in the studies in state schools are increasing, for the most part these have been young people from religious schools. They have shown the capacity to put aside their own judgment and presumably many years of “confessional” religious education to enter into the religious worlds of others and, having done so successfully, to be judged by external examiners. Indeed, a certain natural suspension of religious convictions usually occurs for even religiously committed young people in their teenage years. Interestingly enough it was the Catholic religious educator, Gerard Rummery (1975), who claimed that phenomenology may be just the method for these young people, because it provides a climate where their own religious doubts would not be the focus of attention in the religious education curriculum. Weigh up these debates and write up to 200 words on the appropriateness of some use of phenomenology in your religious education context. Conclusion Phenomenology has been a force in religious education theory since at least the 1960s. Its longevity attests both that it works and that it is has much to offer the multireligious world in which the young people of Western secular societies live. Philip Barnes will probably argue, correctly, that the description and analysis of phenomenology contained in this chapter has again avoided the issue of which religion, if any, is right, that is has not addressed the complex question of religious truth claims and the need for religious education to take account of these. This, however, is not the central issue for school curricula, with their young, captive and often disinterested audience, and it is around school curricula that discussions of phenomenology usually revolve. Teenagers cannot be expected to make a decision about whether this religion is right and this other wrong, especially when they live in families and communities where, for the most part, religion is a minor part of life if it encroaches on life at all. The task of the school years is to learn about the world in which one lives, and to begin to sharpen the critical faculties that will help one to make complex judgments in later years. The truth claims of religions must be assessed if any meaningful commitment to a tradition is to occur, but no-one can seriously expect children and young people to do this in any but the most obvious cases. The Catholic theologian, Hans Kung (1974), both argues for a critical assessment of the truth claims of religions and provides criteria by which this assessment may proceed, but he directs his advice to adult Christians taking part in inter-faith dialogue, not to children in schools. Moran (1983) also argues that the critical dialogue that occurs by bringing one’s own tradition face to face with another, carefully explaining differences and discussing one’s own religious convictions while still growing in respect for the other, is a task of adulthood. Careful attention to the skills implied in the phenomenological method in religious education may well prepare the way for this critical assessment later in life. REFERENCES Barnes, P. (2001). What is wrong with the phenomenological approach to religious education? Religious Education. 96, 445–461. Barnes, P. (2001a). Ideology, phenomenology and hermeneutics. A response to Professor Lovat. Religious Education, 96, 445–461. Crawford & Rossiter. (1995). The spiritual formation of young Catholics through religious education. The Living Light. Durkheim, E. (1976). The elementary forms of the religious life (2nd ed.). London: George, Allen and Unwin. Eisner, E. (1979). The educational imagination. New York: Macmillan. Engebretson, K. (1995). The approach to religious education in the Victorian Certificate of Education. Word in Life. Eliade, M. (1958). Patterns in comparative religion. London: Sheed and Ward. Grimmitt, M. (1973). What can I do in RE? Great Wakering: Mayhew-McCrimmon ____________(1987). Religious education and human development. Great Britain: Mc Crimmon. ____________(2000). Constructivist pedagogies of religious education project: Re-thinking knowledge, teaching and learning in religious education. In M. Grimmitt (Ed.), Pedagogies of religious education (pp. 189-207). Great Wakering: McCrimmon. Habel, N. & Moore, B. (1982). When religion goes to school: Typology of religion for the classroom. Adelaide: South Australian College of Advanced Education. Habermas, J. (1972). Knowledge and human interests, (Tr. J. Shapiro). London: Heinemann. Habermas, J. (1974). Theory and practice. Boston: Beacon Press. Hick, J. (1991). An interpretation of religion. London: McMillan. Hull, J. (1984). Studies in religion and education. Basingstoke, England: Falmer. Husserl, E. (1958). The idea of phenomenology, (Tr.W. Alston & G. Nakhnikian). The Hague: Nijhoff. Husserl, E. (1982). Ideas pertaining to a pure phenomenology and to a phenomenological philosophy, (Tr. F. Kersten). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. Kung, H. (1974). On being a Christian. London: Collins. Lovat, T. (1995). Teaching and learning religion: A phenomenological approach. Wentworth Falls, N.S.W: Social Science Press. Lovat, T. (2001). In defence of phenomenology. Religious Education, 96(4), 564–570. Lovat, T. (2002). What is this thing called religious education? Katoomba, NSW: Social Science Press. Lovat, T. (2005). The agony and the ecstasy of phenomenology as a method: the contribution to Australian religious education. Journal of Religious Education, 53(2), 46–51. Moran, G. (1983). Religious education development. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Winston Press. Nesbit, R. (1976). Introduction. In E. Durkeim, The elementary forms of the religious life (2nd ed.), (pp. 1-2). London: George, Allen and Unwin. Otto, R. (1958). The idea of the holy. London: Oxford University Press. Rossiter, G. (1985). The place of faith in classroom religious education. Catholic Schools Studies, 59(2), 49–55. Rummery, R. M. (1975). Catechesis and religious education in a pluralist society. Sydney: E. J. Dwyer. Smart, N. (1968). Secular education and the logic of religion. London: Faber. Smart, N. (1974). The science of religion and the sociology of knowledge. New Jersey: Princeton University. Smart, N. (1976). The religious experience of mankind. London: Collins. Smart, N. (1979). Background to the Long Search. London: BBC. Wittgenstein, L. (1958). Philosophical investigations. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell. _____________(1969). On certainty. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell.