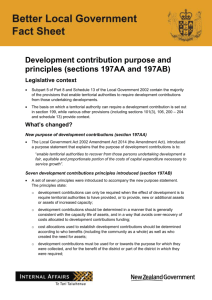

The context for development contributions

advertisement