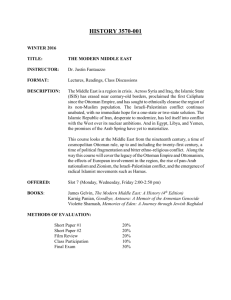

File

advertisement

MEMORY OF THE WORLD Turkey - Manuscripts of Kandilli Observatory The aim of this project is the preservation of a collection of about 1300 works on astronomy in three languages (Turkish, Persian and Arabic) held in the Library of Kandilli Observatory and Earthquake Research Institute at Bogaziçi University in Istanbul. Mathematics, medicine and astronomy were the core disciplines of Islamic science in the Ottoman Empire. The collection in the Library of the Kandilli Observatory and Earthquake Research Institute specializes in astronomical, astrological, mathematical and miscellaneous works. This is perhaps the only collection in the world that houses manuscripts on related subject matters. Therefore, it is significant for those scholars and experts who are interested in these subjects and Ottoman and Islamic cultural structure. The collection in the library comprises a total of 1339 works in 581 volumes. 822 of the works are in Turkish, 414 are in Arabic and 103 are in Persian. Since this collection consists of a number of unique and rare manuscripts it occupies an important place among other manuscript collections in the world. There is no preservation budget. The collection is stored in a single room in glass cabinets and the manuscripts are put into individual envelopes. There are no special regulations of room temperature or humidity. The manuscripts have been microfilmed for recovery purposes. There is no preservation staff, but one person has been assigned responsibility for these manuscripts. The collection holds 1339 works in astronomy, astrology, mathematics, geography and miscellaneous written in various dates from 11th to the early 20th centuries. In the Islamic world, astronomical and astrological works and calendars were used in the following areas: determining the proper time for planting and harvesting in farming, determining eclipses of the sun and moon, determining the appropriate organization of one’s day, ship navigation (for example, when the rûz-i Kasim or the winter arrives the ships come into harbour and war and merchant ships do not navigate), finding directions and the time with an astrolabe; determining prayer times in accordance with the position of the sun, determining sunrise and sunset as well as the rising and setting of the moon, determining the arrival of Nevrûz (the first day of spring) and the start of the Celâlî year according to Nevrûz, setting the time for judicial events and organizing social life, such as setting work hours. In other words, astronomical and astrological works were extremely important in organizing daily, religious, judicial and social activities. The first calendar that occupies a significant place in the Islamic world is Turkish and was presented to Fatih Sultan Mehmet (Mehmet the Conqueror). This work, entitled Takvîm ve ahkâm-i sâl, comprises tables of the names of the Ottoman Sultans up to Fatih Sultan Mehmet, shows the signs of stars and planetary houses, the qualities of good and bad vibrations in the body, superstitious observances related to the stars and planets and the four seasons of the year. This calendar was prepared for the year 1452 AD (See Fehmi Edhem Karatay, Topkapi Saray Müzesi Kütüphanesi Türkçe Yazmalar Katalogu, v. 1, Istanbul: Topkapi Sarayi Müzesi, 1961, p. 536). The Kandilli collection contains another calendar in Persian prepared in 1489-90 AD and presented to Sultan Beyazit. As seen in Bayezit's own manuscripts, the Sultan's personal seals are found at the beginning and end of this calendar. In addition, since this collection contains works on astronomy, astrology, mathematics and geography produced over many centuries, it reflects the cultural and scientific accumulation of a nation. In particular, the rûznâmes are important in showing the religious festivals and prayer times of the time in the Islamic world. In his work Osmanli Türklerinde Ilim, Abdülhak Adnan Adivar (See Abdülhak Adnan Adivar, Osmanli Türklerinde Ilim, 2th ed., Istanbul: Maarif Vekaleti, 1943 and A[bdülhak] Adnan Adivar, Osmanli Türklerinde Ilim, 3th ed., Istanbul: Remzi, 1970) traces the history of science among the Ottoman Turks, relying on various sources found in the Kandilli Observatory Library (including Lalande's Tables astronomiques, a Turkish copy of Cassini's tables of astronomy and Takiyeddîn's Âlâtu’l-rasadiye li-zîc-i sehinsâhiye etc). Since some works in this collection are not known by numerous scholars and experts they possess importance of an original nature. The oldest works in this collection are Risâle-i sî-fasl, translated into Turkish by Ahmed-i Daî (died after 824/1421) from Persian in the first half of the 15th centry, Tahdîd nihâyât alamâkin tashîh masâfât al-masâkin in Arabic by Birunî (362-443/973-1051) in 1025 AD and Lubab al-ihtiyarât fî ta’yîn al-awkât in Persian by Husayn b. Ali b. Hasan Bayhakî al-Kâsifî Husayn Waiz (died 910/1505) in 1461-62 AD. A gurrename is the Turkish word for an Ottoman book -- concerned with the first day(s) of the lunar month(s). TULIPS Everybody thinks that tulips come from Holland. Actually, Tulips are native to Central Asia and Turkey. In the 16th Century they were brought to Holland from Turkey, and quickly became widely popular. Today Tulips are cultivated in Holland in great numbers and in huge fields. Dutch bulbs, including tulips and daffodils, are exported all around the world so people think that it's originated from there as well. In fact many cultivated varieties were widely grown in Turkey long before they were introduced to European gardens. The period in our history between 1718-1730 is called the "Tulip Era", under the reign of sultan Ahmed III. This period is also expressed as an era of peace and enjoyment. Tulips became and important style of life within the arts, folklore and the daily life. Many embroidery and textile clothing handmade by woman, carpets, tiles, miniatures etc. had tulip designs or shapes, large tulip gardens around the Golden Horn (a horn-shaped estuary, dividing the European side of Istanbul.) were frequented by upscale people, and so on. Also, the first printing house was founded by Ibrahim Müteferrika in Istanbul. The Tulip Era was brought to an end after the Patrona Halil revolt in 1730, ending with the dethronation of the Sultan. The botanical name for tulips, Tulipa, is derived from the Turkish word "tulbend" or "turban", which the flower resembles. It's considered as the King of Bulbs. Like many other products in western Europe, such as the potato and tobacco, tulips came to the Netherlands from another part of the world. Not introduced to the Netherlands until 1593, the tulip was first seen by Europeans in Turkey. It was there in 1556 that Busbeq (A.G. Busbequius), the ambassador sent by the Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I to the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, witnessed the flowers growing in the gardens of Adrianople and Constantinople. Scholars now believe that the Turks had been cultivating tulips as early as AD 1000. Most of these tulips probably originated in areas around the Black Sea, in the Crimea, and in the steppes to the north of the Caucasus. Soon after Ambassador Busbeq noticed the flowers in the Ottoman Empire, tulips became one of the most sought after luxury items in Europe. At first, in the 1560s, trade and diplomatic interaction with the Ottoman Levant allowed for a small number of tulips to be imported into Hapsburg Europe. In this early stage, tulip ownership was primarily limited to wealthy nobles and scholars. Antwerp, Brussels, Augsburg, Paris, and Prague are among some of the cities where such tulips first began to circulate. A key figure in the history of European tulip interest is the famous botanist Carolus Clusius. Clusius, who had achieved great recognition for his work with medicinal herbs in Prague and Vienna, accepted a position as head botanist of the Dutch university in Leiden in the year 1593. Previously, he had met with former Ambassador Busbeq in Vienna and accepted several tulip bulbs and seeds. At Leiden’s innovative hortus botanicus, or botanical garden, Clusius cultivated the bulbs and seeds and thus introduced the flower to Holland. Through botanical experimentation, Clusius and other horticulturists produced new color variations in tulips. This breeding of tulips with new color combinations had two important effects on the European — primarily Dutch — tulip market. The most elegantly and vividly colored of the new tulips, such as the Semper Augustus, which was white with red flames, became exorbitantly priced. Only the wealthiest aristocrats and merchants could afford these striped hybrid varieties. By the early 1630s, however, flower growers had begun to raise vast crops of more simplycolored tulips. These flowers, such as the Yellow Crown tulips, could be purchased cheaply by even the poorer segments of society. With an evergrowing number of varieties and an ever-widening price range, tulips became one of the few luxury goods that could be purchased by members of all classes. The popularity of the tulip in the Dutch Republic reached its pinnacle in the years 1636-37 during the craze known as ‘tulip mania.’ II Ala al-Dīn Ali Kuşçu (1403 – 16 December 1474) was an astronomer who He worked at this observatory in Samarkand, Uzbekistan (its ruins were discovered by Russian archeologists in 1908. This one was built in its honour in 1970s) Ulugh Beg wrote the Zij-i-Sultani in 1437. For a century it was considered the most accurate and extensive star catalogue until its time. This sort of work is now being done by huge telescopes sent into outerspace. Ulugh Beg (who was eventually assassinated) built this madrasah in 1420s The commentator was Muslih al-Din al-Ansari al-Lari. He taught the Moghul emperor Humayun,(1530-56). He was a Persian scholar and historian who after Humayun's death, established himself as a merchant in Aleppo an Istanbul. He wrote numerous annotations on numerous worksof philosophy and logic. then added the observatory The city of Samarkand is most noted for its central position on the Silk Road between China and the West, (it is mentioned in Marco Polo's Travels) and it is also famous for being an Islamic centre for scholarly study. This is the Registan, the ancient centre of the city Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka, winner of the 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature, explores the metaphysical significance of the marketplace in a volume of poetry entitled Samarkand and Other Markets I Have Known, 2002. To hear him read from this collection go to: http://forum-network.org/tags/samarkand-other-markets-i-have-known scoll forward to 46 minutes......to hear it The Bibi-Khanym Mosque remains one of the city's most famous landmarks. (This is what it looked like in 1907; taken by color photography pioneer Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii It shows the mosque's appearance after its collapse in the earthquake of 1897.) It was built with precious stones from India between 1399 and 1404 Today it looks like this (none of the orginal remains): CLIKC ON THIS HYPERLINK TO GO ON A 3D TOUR OF THIS MOSQUE http://www.world-heritage-tour.org/asia/central-asia/uzbekistan/samarkand/bibi-khanymmosque/sphere-quicktime.html http://www.scribd.com/doc/9376276/Cultural-Translation-in-Early-Modern-Europe this is a book edited by Peter Burke Got to Page 204 for the chapter on the translation of European Turkish culture III IV Risala means “message” in Arabic. In Islam it has a broader meaning. dar hay a, written in Persian in 1235; its appen- dix the Hall-i mushkildt-i Mu Tnniya, also writ- ten in Persian, probably shortly after the Risalah- Ris¯ala dar hay'a ("Treatise on Spherical Astronomy") by the IV irtifa means 'altitude' V Marifet-name by İbrahim Hakkı Erzurumi Book of Gnosis Ibrahim Hakkı Erzurumi (18 May 1703 – 22 June 1780) was a Turkish and Sufi philosopher and encyclopedist. In 1756 he published his work Marifetname (Book of Gnosis) which was a compilation and commentary on astronomy, mathematics, anatomy, psychology, philosophy, and Islamic mysticism. It is famous for containing the first treatment of postCopernican astronomy by a Muslim scholar. is generally understood to be the inner, mystical dimension of Islam Oriental medical manuscripts of Uzbekistan were not extensively studied. The last twenty years, however, brought Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan to semi-isolation. For centuries Uzbekistan had intensive relationships with these countries in many ways including medical. Many medical manuscripts were brought to Uzbek states (1) from different parts of Islamic world. Many works, including some writings of Abu Ali Ibn Sina (Avicenna) were composed there. IX Taqi al-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf al-Shami al-Asadi (Arabic: تقي الدين محمد بن معروف الشامي السعدي, Turkish: Takiyuddin) (1526–1585) was a major Ottoman Turkish[1] or Arab[2] Muslim polymath: a scientist, astronomer and astrologer, engineer and inventor, clockmaker, physicist and mathematician, botanist and zoologist, pharmacist and physician, Islamic judge and mosque timekeeper, Islamic philosopher and theologian, and madrasah teacher. He was the author of more than 90 books on a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, astrology, clocks, engineering, mathematics, mechanics, optics and natural philosophy,[3][4] though only 24 of those works have survived.[4] He was widely regarded by his contemporaries in the Ottoman Empire as "the greatest scientist on earth".[5][6] One of his books, Al-Turuq al-samiyya fi al-alat al-ruhaniyya (Arabic: ()الطرق السامية في اآلالت الروحانيةThe Sublime Methods of Spiritual Machines) (1551), described the workings of a rudimentary steam turbine, predating the more famous discovery of steam power by Giovanni Branca in 1629.[7] Taqi al-Din is also known for the invention of a six-cylinder 'Monobloc' pump in 1559, the invention of a variety of accurate clocks (including a weight-powered astronomical clock with an alarm)[8][9] from 1556 to 1580, the possible invention of an early telescope some time before 1574,[4] his construction of the Istanbul observatory of Taqi al-Din in 1577, and his astronomical activity there until 1580. Taqi al-Din was born in 1521 in Damascus, Syria, and was educated in Cairo, Egypt. He became a qadi (judge in Islamic law), Islamic theologian, muwaqqit (religious timekeeper) at a mosque and teacher at a madrasah for some time, while publishing a number of scientific books during this time. In 1571, he moved to Istanbul to become the official astronomer for Sultan Selim II of the Ottoman Empire. When Selim II died, Murad III became the new sultan, and Taqi al-Din convinced Murad to fund the building of a new observatory on the basis that it would help in making accurate astrological predictions. The project began in 1575,[2] and was completed in 1577, at nearly the same time as Tycho Brahe's observatory at Uraniborg. This would become known as the Istanbul observatory of Taqi al-Din, an observatory built to rival Ulugh Beg's Samarkand observatory. At the new observatory, Taqi al-Din updated the old Zij astronomical tables, particularly Ulugh Beg's Zij-i-Sultani, describing the motions of the planets, sun, moon and stars.[3][10] He invetned a framed sextant similar to what Tycho Brahe later used as shown in the picture Alat ar-Ruhaniyya measn the Sublime Method of Spiritual Machines n 16th-century Damascus, the polymath judge Taqi al-Din penned some 19 books on physics and hydraulics, including the intriguingly titled Al-Turuq alSaniyya fi al-Alat al-Ruhaniyya (Sublime Methods of Spiritual Machines), an illustrated catalog written around 1551 that describes clocks, pumps, loadlifting equipment and other contrivances, including a water-powered sixcylinder “monobloc” pump. Its scoop paddlewheel turns an axle that sets cams and piston rods in motion, drawing water through a series of valves and accelerating it with great force into a delivery pipe. In the West, ironically, Agostino Ramelli, Italian physicist and author of the 1588 tome Le diverse et artificiose machine, received credit for devices Taqi al-Din had published 37 years earlier.